4 Active Learning and Projects Course Resource Book

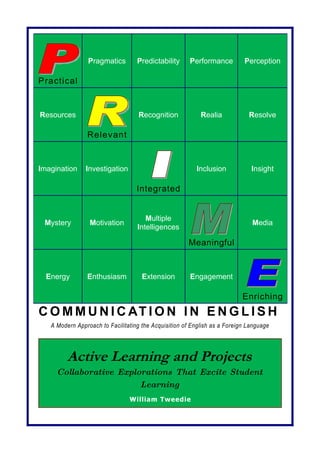

- 1. Pragmatics Predictability Performance Perception Practical Resources Recognition Realia Resolve Relevant Imagination Investigation Inclusion Insight Integrated Multiple Mystery Motivation Media Intelligences Meaningful Energy Enthusiasm Extension Engagement Enriching C O M M U N I C AT I O N I N E N G L I S H A Modern Approach to Facilitating the Acquisition of English as a Foreign Language Active Learning and Projects Collaborative Explorations That Excite Student Learning William Tweedie

- 2. Part 4 of the PRIME Teacher Training Program Active Learning and Projects Collaborative Explorations That Excite Student Learning Course Reference Book William Tweedie 2

- 3. © 2005 - 2010 Kenmac Educan International & William M Tweedie TABLE OF CONTENTS COURSE OUTLINE............................................................................................................................4 ACTIVE LEARNING AND THE LIMITED ENGLISH PROFICIENT STUDENT ..............................................5 GROUP WORK, INTERLANGUAGE TALK, AND SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION............................10 PROJECT-BASED LEARNING FOR ADULT ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS ........................................20 THE PROJECT APPROACH...............................................................................................................24 PROJECT-BASED INSTRUCTION: CREATING EXCITEMENT FOR LEARNING.........................................27 SOME EXAMPLES:..........................................................................................................................35 ONLINE RESOURCES FOR PROJECT IDEAS.......................................................................................43 REFERENCES..................................................................................................................................43 PROJECTS: EXPLORE, QUESTION, PONDER, AND IMAGINE..............................................................46 THEMATIC TEACHING IN ACTION...................................................................................................50 Articles are the property of the authors and copyright owners. Permission is granted for reproduction. Please cite the authors and source. 3

- 4. Course Outline 1. What is Active Learning (AL)? a. Review of main points b. Levels of Engagement (LOE) c. LOE and Group Work 2. What is Project Based Learning (PBL)? a. Project Based Learning and Activities i. What is an Activity? ii. What is a Project? b. Principles of PBL c. Phases in PBL 3. Managing Project Based Learning a. Project 1 - Mini b. Practice in Preparing for Project Work 4

- 5. Directions in Language and Education National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education Vol. 1 No. 2 Active Learning and the Limited English Proficient Student By Veronica Fern, Kris Anstrom, and Barbara Silcox In June 1993, the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (OBEMLA) convened a focus group which studied active learning and its implications for limited English proficient (LEP) students. Discussions focused on the following questions: 1) What is active learning? 2) What does active learning mean for LEP students? 3) What are the instructional implications of active learning in the LEP classroom? and 4) What are the implications of active learning for teacher training? The conclusions reached by the focus group were published by the Special Issues Analysis Center (SIAC), Special Issues Analysis Center focus group report: Active learning instructional models for limited English proficient (LEP) students; Volume 1: Findings on active learning , by L. Lathrop, C. Vincent and A.M. Zehler (1993). This synthesis is based largely on that report. What Is Active Learning? All learning is in some sense active, but active learning refers to the level of engagement by the student in the instructional process. An active learning environment requires students and teacher to commit to a dynamic partnership in which both share a vision of and responsibility for instruction. In such an environment, students learn content, develop conceptual knowledge, and acquire language through a discovery-oriented approach to learning in which the learner is not only engaged in the activity but also with the goal of the activity. Essential to this approach is the view of the learner as responsible for discovering, constructing and creating something new and the view of the teacher as a resource and facilitator. In an active learning environment the students should gain a sense of empowerment because the content presented and ideas discussed are relevant to their experiences and histories. For example, the teacher might present a list of thematic units to the students, who then decide what aspects of the themes they wish to investigate and which activities will allow them to pursue that theme. Theoretical Bases of Active Learning Active learning derives its theoretical basis from the situated cognition theorists such as Paolo Freire, whose main pedagogical philosophy revolves around the idea that instruction is most effective when situated within a student's own knowledge and world view. Thus the student's culture and community play a significant role in learning. L.S. Vygotsky's "zone of proximal development" theory supports the idea that students learn best when new information presented is just beyond the reach of their present knowledge. What Does Active Learning Mean For LEP Students? Active learning implies the development of a community of learners. Essential to this development is communication which involves all students, including LEP students, in sharing information, questioning, relating ideas, etc. This emphasis on communication provides many situations where students can produce and manipulate language to support a variety of goals. In other words, active learning supports opportunities for authentic communication rather that rote language drills. Additionally, integration of the student's home, community and culture are essential elements of the active learning approach. A strong home-school connection is often cited as a positive factor in the achievement of minority students. For example, Luis Moll's "Funds of Knowledge" model assumes that language minority students come to school with knowledge and strengths that should be utilized by the school. 5

- 6. Parent and Community Involvement Because of the importance of the home/school connection for implementation of the active learning model, it is essential to keep certain considerations in mind for limited English proficient students. For example, often parents of LEP students face socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic barriers which prevent them from being active participants in their children's schools. Getting these parents involved in the active learning process usually necessitates a systematic program of reaching out to parents and the community. Goals for LEP Students In an active learning environment all students, including LEP students, work toward certain goals. These include "engagement in learning; the development of conceptual knowledge and higher order thinking skills; a love of learning; cognitive and linguistic development; and a sense of responsibility or 'empowerment' of students in their own learning." (Lathrop et al., 1993, p. 6) However, LEP students also need to learn to speak, understand, read and write English. Active learning provides the context LEP students need to meet these goals by giving them opportunities to practice English and providing them with the motivation to do so. A second goal which active learning emphasizes for LEP students is equal access to the content curriculum. Finally, depending upon circumstances within each school, native language development may also be a goal. Modifications for LEP Students The use of active learning for limited English proficient students necessitates certain modifications of the model to ensure its effectiveness with these students. Teachers must be aware of and sensitive to cultural and linguistic differences of their students and remain open to the possibility of learning about them. Furthermore, they need to be skilled at teaching language and content simultaneously, as students are learning both at the same time. Teachers should provide a safe and predictable environment for their students, which reduces student anxiety and nurtures contextual meaning for them. Also, teachers need to explicitly teach sociolinguistic behaviors such as, when students should and should not speak, how students should interact with others, and what school routines and norms are. Instructional Implications of Active Learning in the LEP Classroom Effective active learning principles Certain principles or practices have proven to be highly effective when implemented in the active learning classroom for LEP students. These principles can be classified into the following areas: classroom environment, including organization and ambiance; structure of interaction; and approaches to making content instruction more comprehensible for LEP students. The general classroom environment should be such that students feel safe and comfortable. A predictable structure, explicitly defined rules, and structured routines help to reassure students; graphic organizers aid students' understanding. Classes of fewer students function better in the context of this model. The physical environment of the classroom reflects the active learning process: furniture is made into flexible, moveable arrangements; and learning centers or small group discussion areas are typical of the active learning classroom. The active learning classroom promotes a variety of interactive structures including, but not limited to, whole-group teacher- directed instruction. A range of groupings such as small group work, one-on- one instruction with the teacher, and peer teaching should be used. Student groupings should be carefully planned for heterogeneity of English skill level and content level knowledge. On the other hand, if a particular skill needs to be developed, homogeneous groups may be used for that purpose. Approaches for making content instruction more comprehensible include: cooperative learning; the use of manipulatives; visual organizers and other extra-linguistic support; avoiding idioms, unless explained to students; one-on-one conferencing; availability and use of support materials in the student's native language; the use of dialog journals; and content that is relevant and meaningful to students. Activities and assessments should be compatible with each student's English level. 6

- 7. Suggestions and strategies for using the active learning instructional model with limited English proficient students can be found in Working with English Language Learners: Strategies for Elementary and Middle School Teachers. NCBE Program Information Guide, No. 19 1994 Active learning at the secondary level Elementary schools, in many cases, already practice many behaviors associated with the active learning model; therefore, the model is more easily adaptable to the elementary school culture than it is to the secondary schools. Moreover, the traditional methods of instruction in secondary schools are generally not conducive to the active learning model. Thus, changing over to this model requires a whole-school restructuring effort. Secondary teachers generally see many students for short periods of time each day and deliver their instruction in lecture format. The secondary disciplines tend to be compartmentalized rather than integrated; teachers are expected to be experts in their field and often do not know their individual students very well. Further complicating matters for LEP students, each content area has discipline-specific discourse structures and ways of knowing which must be learned. At the secondary level, there is tremendous diversity among LEP students in terms of their years of schooling and patterns of success and failure. Additionally, most secondary schools operate on a system of credits, causing many LEP students to race against the clock in order to earn enough credits to graduate while attempting to catch up simultaneously in both content knowledge and English skills. Measurement of Outcomes (Assessment) Assessments should be aligned with the instructional activities and goals of the active learning model. For this reason, the model depends on the use of a variety of standard and alternative assessment instruments. For example, instruction involving use of the scientific method to solve a problem would be better assessed through a performance based method than with a multiple choice test. Positive instructional outcomes of active learning anticipated for LEP students include: an interest in and love of learning; improved higher order thinking skills; concept acquisition and content knowledge; and English language skills. Furthermore, students in active learning classrooms should be assessed for engagement in learning. What Do Active Learning Approaches Imply For Teacher Training? All teachers, including mainstream teachers, should be trained to work with LEP students using active learning approaches. Preservice teachers can be taught via active learning activities in order to give them firsthand experience with the model. In addition they need more school-based experiences in multicultural settings than is provided by student teaching. At the inservice level, implementing the active learning model involves understanding the most effective ways to promote change. All school personnel need to be involved in developing commitment and support for school-wide change to the active learning model. Inservice teachers need ongoing staff development tailored to their needs as well as training in the theory and methodology of second language acquisition. Most importantly, they need to be provided with the time and opportunity to reflect on their own practice, to share experiences with one another, discuss problems, and build future goals together for their students and schools. Recommendations for Active Learning in the Classroom • Use flexible room arrangements to encourage interaction and sharing of ideas and tasks. • Specifically explain rules and procedures to students. • Create predictability in classroom routines. • Provide for small class sizes where possible. • Make the teacher a guide and facilitator, rather than a disseminator of information. • Encourage students to tap into each other's knowledge and experience and build networks for accomplishing goals. • Integrate language, culture and community resources into instructional activities. • Incorporate out-of-school experiences into classroom practice. • Be flexible and create in the use of resources, curricula, and teaching strategies. • Use a variety of grouping strategies: small groups, pairs, individual. • Vary the composition of the groups in terms of the mix of LEP and non-LEP students, depending upon the goals of the activity and the skill levels of the students. 7

- 8. • Focus on activities that promote production of language. • Assess for content achievement and progress using a variety of assessment measures, including performance and portfolio assessment, that are appropriate and consistent with instruction. • Monitor continuously to ensure student engagement. Recommendations for Active Learning in the School • Involve the principal to get his or her full support. • Involve all teachers, not only those whose instruction is focused on LEP students. • Empower the teachers to make decisions and take a leadership role. • Build teamwork within the school community by developing mechanisms for collaboration among staff. • Develop a multi-year staff development plan. • Incorporate the home and community in planning and carrying out activities. • Develop multicultural awareness throughout the school, in which non-English home languages and cultures are integrated in all curricula and activities. • Represent non-English language groups in faculty and support staff positions. Recommendations for Parents and the Community • Involve parents in the school at many levels. • Explain the goals of active learning to parents. Help them understand the rationale behind what their children do in school in an active way. • Inform parents explicitly about ways in which they can help their children learn and/or assist the school. • Open up the school to the community. • Develop mechanisms for drawing on community knowledge and resources. • Develop support for teachers and the principal to carry out home visits and other means of learning about the homes/communities of the students. Recommendations for Teacher Preparation • Give pre-service teachers a variety of school-based experiences that involve learning about students and their communities. • Use active learning approaches to train teachers. • Give teachers experiences in a language and culture different from their own. • Encourage reflective practice. • Develop multi-year plans for inservice training. • Base inservice training on the needs identified by teachers. • Provide inservice training on an ongoing basis, including classroom-based support for teachers involved in implementing active learning. • Encourage highly skilled teachers to act as coaches or mentors for peers. • Encourage teachers to attend professional conferences both as learners and presenters. • Provide training in active learning approaches to all teachers, not just ESL/bilingual education specialists. Resources Publications Which Include A BE Number And A Price Are Available From NCBE. Clifford, S. (1993). Bringing history alive in the classroom. Social Studies Review, 32, 12-16. Fathman, A. K., Quinn, M. E., & Kessler, C. (1992) Teaching Science to English learners, grades 4-8. NCBE Program Information Guide, No. 11. (BE018764) ($3.50) Gill, J. A. M. (1993). Active participation in the classroom: Student and teacher success. Social Studies Review, 32, 21-25. 8

- 9. Kinsella, K. (1991, December) Empowering LEP students with active learning strategies. MRC Memorandum. ARC Associates: Oakland, CA. (BE019154) ($1.00) Lathrop, L. Vincent, C. & Zehler, A. (1993). Special Issues Analysis Center focus group report: Active learning instructional models for limited English proficient (LEP) students. (BE019269) (Volume 1: Findings on active learning. $13.60; Volume 2: Transcript of Focus Group Meeting. $57.30) Matthews, D. (1993). Action based learning environments. Social Studies Review, 32 17-20. Menkart, D. (1993). Multicultural education: Strategies for linguistically diverse classrooms. NCBE Program Information Guide, No. 16. (BE019274) ($3.50) Sasser, L. & Winningham, B. (1994). Sheltered instruction across the disciplines: Successful teachers at work. In With different eyes: Insights into teaching language minority students across the disciplines. White Plains, NY: Longman. Simich-Dudgeon, C. (1992). Second-language learning: Home, Community, and School Factors. ASCD Curriculum Technology Quarterly, 2, 2, 1-4. Violand-Sanchez, E.; Sutton, C. P. & Ware, H. W. (1991). Fostering home-school cooperation: Involving language minority families as partners in education. NCBE Program Information Guide, No. 6. (BE108136). ($3.50) Zehler, Annette. (1994). Working with English Language Learners: Strategies for Elementary and Middle School Teachers. NCBE Program Information Guide, No. 19. ($3.50) Videos Available From NCBE Hammond, Lorie (Producer) (1992). Constructivist science for the language minority child. Video produced by the Title VII BICOMP, Washington Unified School District, West Sacramento, CA. VHS format; 25 minutes; cost: $15.00. Innovative Approaches Research Project (Producer). (1990) Cheche Konnen: Scientific inquiry in the language minority classroom. VHS format; 14 minutes; cost: $15.00. 9

- 10. Group Work, Interlanguage Talk, and Second Language Acquisition Michael H. Long, University of Hawaii at Manoa and Patricia A. Porter, San Francisco State University The use of group work in classroom second language learning has long been supported by sound pedagogical arguments. Recently, however, a psycholinguistic rationale for group work has emerged from second language acquisition research on conversation between non-native speakers, or interlanguage talk. Provided careful attention is paid to the structure of tasks students work on together, the negotiation work possible in group activity makes it an attractive alternative to the teacher-led, “lockstep” mode and a viable classroom substitute for individual conversations with native speakers. For some years now, methodologists have recommended small group work (including pair work) in the second language classroom. In doing so, they have used arguments which, for the most part, are pedagogical. While those arguments are compelling enough, group work has recently taken on increased psycholinguistic significance due to new research findings on two related topics: 1) the role of comprehensible input in second language acquisition (SLA) and 2) the negotiation work possible in conversation between non-native speakers, or interlanguage talk. Thus, in addition to strong pedagogical arguments, there now is psycholinguistic rationale for group work in second language learning. Pedagogical Arguments for Group Work There are at least five pedagogical arguments for the use of group work in second language (SL) learning. They concern the potential of group work for increasing the quantity of language practice opportunities, for improving the quality of student talk, for individualizing instruction, for creating a positive affective climate in the classroom, and for increasing student motivation. We begin with a brief review of those arguments. Argument 1 - Group work increases language practice opportunities. In all probability, one of the main reasons for low achievement by many classroom SL learners is simply that they do not have enough time to practice the new language. This is especially serious in large EFL classes in which students need to develop aural-oral skills, but it is also relevant to the ESL context. From observational studies of classrooms (e.g., Hoetker and Ahlbrand 1969 and Fanselow 1977), we know that the predominant mode of instruction is what might be termed the lockstep, in which one person (the teacher) sets the same instructional pace and content for everyone, by lecturing, explaining a grammar point, leading drill work, or asking questions of the whole class. The same studies show that when lessons are organized in this manner, a typical teacher of any subject talks for at least half, and often for as much as two thirds, of any class period (Flanders 1970). In a 50-minute lesson, that would leave 25 minutes for the students. However, since 5 minutes is usually spent on administrative matters (getting pupils in and out of the room, calling the roll, collecting and distributing homework assignments, and so on) and (say) 5 minutes on reading and writing, the total time available to students is actually more like 15 minutes. In an EFL class of 30 students in a public secondary school classroom, this averages out to 30 seconds per student per lesson—or just one hour per student per year. An adult ESL student taking an intensive course in the United States does not fare much better. In a class of 15 students meeting three hours a day, each student will have a total of only about one and a half hours of individual practice during a six-week program. Contrary to what some private language school advertisements would have us believe, this is simply not enough. Group work cannot solve this problem entirely, but it can certainly help. To illustrate with the public school setting, suppose that just half the time available for individual student talk is devoted to work in groups of three instead of to lockstep practice, in which one student talks while 29 listen (or not, as the case may be). This will change the total individual practice time available to each student from one hour to about five and a half hours. While still too little, this is an increase of over 500 percent. 10

- 11. Argument 2 - Group work improves the quality of student talk. The lockstep limits not only the quantity of talk students can engage in, but also its quality. This is because teacher-fronted lessons favor a highly conventionalized variety of conversation, one rarely found outside courtrooms, wedding ceremonies, and classrooms. In such settings, one speaker asks a series of known information, or display, questions, such as Do you work in the accused's office at 27 Sloan Street?, Do you take this woman to be your lawful wedded wife?, and Do you come to class at nine o’clock? —questions to which there is usually only one correct answer, already known to both parties. The second speaker responds (I do) and then, in the classroom, typically has the correctness of the response confirmed (Yes, Right, or Good). Only rarely does genuine communication take place. (For further depressing details, see, for example, Hoetker and Ahlbrand 1969, Long 1975, Fanselow 1977, Mehan 1979, and Long and Sato 1983) An unfortunate but hardly surprising side effect of this sort of pseudo-communication is that students’ attention tends to wander. Consequently, teachers maintain a brisk pace to their questions and try to ensure prompt and brief answers in return. This is usually quite feasible, since what the students say requires little thought (the same question often being asked several times) and little language (mostly single phrases or short “sentences”). Teachers quickly “correct” any errors, and students appreciate just as quickly that what they say is less important than how they say it. Such work may be useful for developing grammatical accuracy (although this has never been shown). It is unlikely, however, to promote the kind of conversational skills students need outside the classroom, where accuracy is often important but where communicative ability is always at a premium. Group work can help a great deal here. First, unlike the lockstep, with its single, distant initiator of talk (the teacher) and its group interlocutor (the students), face-to-face communication in a small group is a natural setting for conversation. Second, two or three students working together for five minutes at a stretch are not limited to producing hurried, isolated “sentences.” Rather, they can engage in cohesive and coherent sequences of utterances, thereby developing discourse competence, not just (at best) a sentence grammar. Third, as shown by Long, Adams, McLean, and Castaños (1976), students can take on roles and adopt positions which in lockstep work are usually the teacher’s exclusive preserve and can thus practice a range of language functions associated with those roles and positions. While solving a problem concerning the sitting of a new school in an imaginary town, for example, they can suggest, infer, qualify, hypothesize, generalize, or disagree. In terms of another dimension of conversational management, they can develop such skills—also normally practiced only by the teacher—as topic-nomination, turn-allocation, focusing, summarizing, and clarifying. (Some of these last skills also turn out to have considerable psycholinguistic importance.) Finally, given appropriate materials to work with and problems to solve, students can engage in the kind of information exchange characteristic of communication outside classrooms—with all the creative language use and spontaneity this entails—where the focus is on meaning as well as form. In other words, they can in all these ways develop at least some of the variety of skills which make up communicative competence in a second language. Argument 3 - Group work helps individualize instruction. However efficient it may be for some purposes—for example, the presentation of new information needed by all students in a class— the lockstep rides roughshod over many individual differences inevitably present in a group of students. This is especially true of the vast majority of school children, who are typically placed in classes solely on the basis of chronological and mental age. It can also occur in quite small classes of adults, however. Volunteer adult learners are usually grouped on the basis of their aggregate scores on a proficiency test. Yet, as any experienced teacher will attest, aggregate scores often conceal differences among students in specific linguistic abilities. Some students, for example, will have much better comprehension than production skills, and vice versa. Some may speak haltingly but accurately, while others, though fluent, make lots of errors. In addition to this kind of variability in specific SL abilities, other kinds of individual differences ignored by lockstep teaching include students’ age, cognitive/developmental stage, sex, attitude, motivation, aptitude, personality, interests, cognitive style, cultural background, native language, prior language learning experience, and target language needs. In an ideal world, these differences would all be reflected, among other ways, in the pacing of instruction, in its linguistic and cultural content, in the level of intellectual challenge it poses, in the manner of its presentation (e.g., inductive or deductive), and in the kinds of classroom roles students are assigned. 11

- 12. Group work obviously cannot handle all these differences, for some of which we still lack easily administered, reliable measures. Once again, however, it can help. Small groups of students can work on different sets of materials suited to their needs. Moreover, they can do so simultaneously, thereby avoiding the risk of boring other students who do not have the same problem, perhaps because they speak a different first language, or who do have the same problem but need less time to solve it. Group work, then, is a first step toward individualization of instruction, which everyone agrees is a good idea but which few teachers or textbooks seem to do much about. Argument 4 - Group work promotes a positive affective climate. Many students, especially the shy or linguistically insecure, do experience considerable stress when called upon in the public arena of the lockstep classroom. This stress is increased by the knowledge that they must respond accurately and above all quickly. Research (see, for example, Rowe 1974 and White and Lightbown 1983) has shown that if students pause longer than about one second before beginning to respond or while making a response, or (worse) appear not to know the answer, or make an error, teachers will tend to interrupt, repeat, or rephrase the question, ask a different one, “correct,” and/or switch to another student. Not all teachers do these things, of course, but most teachers do so more than they realize or would want to admit. In contrast to the public atmosphere of lockstep instruction, a small group of peers provides a relatively intimate setting and, usually, a more supportive environment in which to try out embryonic SL skills. After extensive research in British primary and secondary school classrooms, Barnes (1973:19) wrote of the small group setting: “An intimate group allows us to be relatively inexplicit and incoherent, to change direction in the middle of a sentence, to be uncertain and self-contradictory. What we say may not amount to much, but our confidence in our friends allows us to take the first groping steps towards sorting out our thoughts and feelings by putting them into words. I shall call this sort of talk exploratory.” I his studies of children’s talk in small groups, Barnes found a high incidence of pauses, hesitations, stumbling over new words, false starts, changes of direction, and expressions of doubt (I think, probably, and so on). This was the speech of children “talking to learn” (Barnes 1973:20) —talking, in other words, in a way and for a purpose quite different from those which commonly characterize interaction in a full-class session. There, the “audience effect” of the large class, the perception of the listening teacher as judge, and the need to produce a short, polished product all serve to inhibit this kind of language. Barnes (1973:19) draws attention to another factor: “It is not only size and lack of intimacy that discourage exploratory talk: if relationships have been formalized until they approach ritual; this, too, will make it hard for anyone to think aloud.” Some classrooms can become like this, especially when the teacher controls very thoroughly everything that is said. In other words, freedom from the requirement for accuracy at all costs and entry into the richer and more accommodating set of relationships provided by small-group interaction promote a positive affective climate. This in turn allows for the development of the kind of personalized, creative talk for which most aural-oral classes are trying to prepare learners. Argument 5 - Group work motivates learners. Several advantages have already been claimed for group work. It allows for a greater quantity and richer variety of language practice, practice that is better adapted to individual needs and conducted in a more positive affective climate. Students are individually involved in lessons more often and at a more personal level. For all these reasons and because of the variety group work inevitably introduces into a lesson, it seems reasonable to believe that group work motivates the classroom learner. Empirical evidence supporting this belief has been provided by several studies reported recently in Littlejohn (1983). It has been found, for example, that small-group, independent study can lead to increased motivation to study Spanish among beginning students (Littlejohn 1982); learners responding to a questionnaire reported that they felt less inhibited and freer to speak and make mistakes in the small group than in the teacher-led class. Similarly, in a study of children’s attitudes to the study of French in an urban British comprehensive school (Fitz-Gibbon and Reay 1982), three quarters of the pupils ranked their liking for French as a school subject significantly higher after competing a program in which 14-yearold non-native speakers tutored 1l-year-old non-natives in the language. Group Work: A Psycholinguistic Rationale 12

- 13. In addition to pedagogical arguments for the use of group work as at least a complement to lockstep instruction, there now is independent psycholinguistic evidence for group work in SL teaching. This evidence has emerged from recent work on the role of comprehensible input in SLA and on the nature of non-native/non-native conversation. It is to this work that we now turn. Comprehensible Input in Second Language Acquisition A good deal of research has now been conducted on the special features of speech addressed to SL learners by native speakers (NSs)of the language or by non-native speakers (NNSs) who are more proficient than the learners are. Briefly, it seems that this linguistic input to the learner, like the speech that caretakers address to young children learning their mother tongue, is modified in a variety of ways to (among other reasons) make it comprehensible. This modified speech, or foreigner talk, is a reduced or “simplified” form of the full, adult NS variety and is typically characterized by shorter, syntactically less complex utterances, higher-frequency vocabulary items, and the avoidance of idiomatic expressions. It also tends to be delivered at a slower rate than normal adult speech and to be articulated somewhat more clearly. (See Hatch 1983 for a review of the research findings on foreigner talk, Chapter 9; for a review of similar findings on teacher talk in SL classrooms, see Gaies 1983a and Chaudron in press) It has further been shown that NSs, especially those (like ESL teachers) with considerable experience in talking to foreigners, are adept at modifying not just the language itself, but also the shape of the conversations with NNSs in which the modified speech occurs. They help their non-native conversational partners both to participate and comprehend in a variety of ways. For example, they manage to make topics salient by moving them to the front of an utterance, saying something like San Diego, did you like it?, rather than Did you like San Diego? They use more questions than they would with other NSs and employ a number of devices for clarifying both what they are saying and what the NNS is saying. The devices include clarification requests, confirmation checks, comprehension checks, and repetitions and rephrasing of their own and the NNSs’ utterances. (For a review of the research on conversational adjustments to NNSs, see Long 1983a.) It is important to note that when making these linguistic and conversational adjustments, speakers are concentrating on communicating with the NNS; that is, their focus is on what they are saying, not on how they are saying it. As with parents and elder siblings talking to young children, the adjustments come naturally from trying to communicate. While their use seems to grow more sophisticated with practice, they require no special training. A recent study by Hawkins (in press) has shown that it is dangerous to assume that the adjustments always lead to comprehension by NNSs, even when they appear to have understood, as judged by the appropriateness of their responses. On the other hand, at least two studies (Chaudron 1983 and Long in press) have demonstrated clear improvements in comprehension among groups of NNSs as a result of specific and global speech modifications, respectively. Other research has demonstrated that the modifications themselves are more likely to occur when the native speaker and the non-native speaker each start out a conversation with information the other needs in order for the pair to complete some task successfully. Tasks of this kind, called two-way tasks (as distinct from one-way tasks, in which only one speaker has information to communicate), result in significantly more conversational modifications by the NS (Long 1980, 1981, 1983 b). This is probably because the need for the NS to obtain unknown information from the NNS makes it important for the NS to monitor the NNS’s level of comprehension and thus to adjust until the NNS’s understanding is sufficient for performance of his or her part of the task. There is also a substantial amount of evidence consistent with the idea that the more language that learners hear and understand or the more comprehensible input they receive, the faster and better they learn. (For a review of this evidence, see Krashen 1980, 1982 and Long 1981, 1983b) Krashen has proposed an explanation for this, which he calls the Input Hypothesis, claiming that learners improve in a SL by understanding language which contains some target language forms (phonological, lexical, morphological, or syntactic) which are a little ahead of their current knowledge and which they could not understand in isolation. Ignorance of the new forms is compensated for by hearing them used in a situation and embedded in other language that they do understand: A necessary condition to move from stage i to stage i + 1 is that the acquirer understand input that 13

- 14. contains i + 1, where “understand” means that the acquirer is focused on the meaning and not the form of the utterance (Krashen 1980:170). Whether or not simply hearing a nd understanding the new items are both necessary and sufficient for a learner to use them successfully later is still unclear. Krashen claims that speaking is unnecessary, that it is useful only as a means of obtaining comprehensible input. However, at least one researcher (Swain in press) has argued that learners must also be given an opportunity to produce the new forms —a position Swain calls the “comprehensible output [italics added] hypothesis.” What many researchers do agree upon is that learners must be put in a position of being able to negotiate the new input, thereby ensuring that the language in which it is heard is modified to exactly the level of comprehensibility they can manage. As noted earlier, the research shows that this kind of negotiation is perfectly possible, given two-way tasks, in NS/NNS dyads. The problem for classroom teachers, of course, is that it is impossible for them to provide enough of such individualized NS/NNS opportunities for all their students. It therefore becomes essential to know whether two (or more) non-native speakers working together during group work can perform the same kind of negotiation for meaning. This question has been one of the main motivations for several recent studies of NNS/NNS conversation, often referred to in the literature as interlanguage talk. The focus in these studies of NNSs working together in small groups is no longer just the quantity of language practice students are able to engage in, but the quality of the talk they produce in terms of the negotiation process. Studies of Interlanguage Talk An early study of interlanguage talk was carried out by Long, Adams, McLean, and Castaños (1976) in intermediate-level, adult ESL classes in Mexico. The researchers compared speech samples from two teacher-led class discussions to speech from two small group discussions (two learners per group) doing the same task. To examine the quantity and quality of speech in both contexts, the researchers first coded moves according to a special category system designed for the study. Quality of speech was defined by the variety of moves, and quantity of speech was defined by the number of moves. The amount and variety of student talk were found to be significantly greater in the small groups than in the teacher-led discussions. In other words, students not only talked more, but also used a wider range of speech acts in the small-group context. In a larger study, Porter (1983) examined the language produced by adult learners in task-centered discussions done in pairs. The learners were all NSs of Spanish. The 18 subjects (12 NNSs and 6 NSs) represented three proficiency levels: intermediate, advanced, and native speaker. Each subject participated in separate discussions with a subject from each of the three levels. Porter was thus able to compare interlanguage talk with talk in NS/NNS conversations, as well as to look for differences across learner proficiency levels. Among many other findings, the following are relevant to the present discussion: 1. With regard to quantity of speech, Porter’s results supported those of Long, Adams, McLean, and Castaños (1976): Learners produced more talk with other learners than with NS partners. In addition, learners produced more talk with advanced-level than with intermediate-level partners, in part because the conversations with advanced learners lasted longer. 2. To examine quality of speech, Porter measured the number of grammatical and lexical errors and false starts and found that learner speech showed no significant differences across contexts. This finding contradicts the popular notion that learners are more careful and accurate when speaking with NSs than when speaking with other learners. 3. Other analyses focused on the interfactional features of the discussions; no significant differences were found in the amount of repair by NSs and learners. Repair was a composite variable, consisting of confirmation checks, clarification requests, comprehension checks, and three communication strategies (verification of meaning, definition request, and indication of lexical uncertainty). Porter emphasized the importance of this finding, suggesting that it shows that learners are capable of negotiating repair in a manner similar to NSs and that learners at the two proficiency levels in her study were equally competent to do such repair work. A related and not surprising finding was that learners made more repairs of this kind with intermediate than with advanced learners. 4. Closer examination of communication strategies, a subset of repair features, revealed very low frequencies of “appeals for assistance” (Tarone 1981), redefined for the Porter study to include 14

- 15. verification of meaning, definition request, and indication of lexical uncertainty. In addition, learners made the appeals in similar numbers whether talking to NSs or to other learners (28 occurrences in 4 ¼ hours with NSs versus 21 occurrences in 4 ½ hours with other learners.) Porter suggested that her data contradict the notion that other NNSs are not good conversational partners because they cannot provide accurate input when it is solicited. In fact, however, learners rarely ask for help, no matter who their interlocutors may be. It would appear that the social constraints that operate to keep foreigner- talk repair to a minimum (McCurdy 1980) operate similarly in NNS/NNS discussions. 5. Further evidence of these social constraints is the low frequency of other-correction by both learners and NSs. Learners corrected 1.5 percent and NSs corrected 8 percent of their interlocutors’ grammatical and lexical errors. Also of interest is the finding that learners miscorrected only .3 percent of the errors their partners made, suggesting that miscorrections are not a serious threat in unmonitored group work. 6. The findings on repair were paralleled by those on another interactive feature, labeled prompts, that is, words, phrases, or sentences added in the middle of the other speaker’s utterance to continue or complete that utterance. Learners and NSs provided similar numbers of prompts. One significant difference, however, was that learners prompted other learners five times more than they prompted NSs; thus, learners got more practice using this conversational resource with other learners than they did with NSs. Overall, Porter concluded that although learners cannot provide each other with the accurate grammatical and sociolinguistic input that NSs can, learners can offer each other genuine communicative practice, including the negotiation for meaning that is believed to aid SLA. Confirmation of Porter’s findings has since been provided in a small-scale replication study by Wagner (1983). Two additional studies of interlanguage talk (Varonis and Gass 1983, Gass and Varonis in press) should be mentioned. In the first study, the researchers compared interlanguage talk in 11 non-native conversational dyads with conversation in 4 NS/NNS dyads and 4 NS/NS dyads. Like the learners in Porter’s (1983) study, the NNSs were students from two levels of an intensive English program; unlike Porter’s subjects, these learners were from two native language backgrounds (Japanese and Spanish). Varonis and Gass tabulated the frequency of what they term nonunderstanding routines, which indicate a lack of comprehension and lead to negotiation for meaning through repair sequences. The main finding in the Varonis and Gass study was a greater frequency of negotiation sequences in non-native dyads than in dyads involving NSs. The most negotiation occurred when the NNSs were of different language backgrounds and different proficiency levels; the next highest frequency was in pairs sharing a language or proficiency level; and the lowest frequency was in pairs with the same language background and proficiency level. On the basis of these findings, Varonis and Gass argue for the value of non-native conversations as a nonthreatening context in which learners can practice language skills and make input comprehensible through negotiation. Building on this study, Gass and Varonis (in press) next examined negotiation by NNSs in two additional communication contexts: what Long (1981) calls one-way and two-way tasks. In the one- way task, one member of a dyad or triad described a picture which the other member(s) drew. In the two-way task, each member heard different information about a robbery, and the dyad/triad was to determine the identity of the robber. The participants, who were grouped into three dyads and one triad, were nine intermediate students from four different language backgrounds in an intensive ESL program. Gass and Varonis looked for differences in the frequency of negotiation sequences across the two task types; they found that there were more indicators of nonunderstanding in the one-way task, but the difference was not statistically significant. They suggest that there may have been more need for negotiation on the one-way task because of the lack of shared background information. A second concern in the study was the role of the participant initiating the negotiation. The finding was not surprising: The student drawing the picture in the one-way task used far more indicators of nonunderstanding than the describer did. A third finding related to the oneway task was a decrease in the number of nonunderstanding indicators on the second trial: Familiarity with the task seemed to decrease the need for negotiation, even though the roles were switched, with the students doing the describing and those doing the drawing changing places. 15

- 16. As in their earlier study, Gass and Varonis argue that negotiation in non-native exchanges is a useful activity in that it allows the learners to manipulate input. When input is negotiated, they maintain, conversation can then proceed with a minimum of confusion; additionally, the input will be more meaningful to the learners because of their involvement in the negotiation process. The importance of learners’ being able to adjust input by providing feedback on its comprehensibility was also stressed by Gaies (1983b). Gaies examined learner feedback to teachers on referential communication tasks. The participants were ESL students of various ages and proficiency levels and their teachers, grouped into 12 different dyads and triads. The students were encouraged to ask for clarification or re-explanation wherever necessary to complete the task of identifying and sequencing six different designs described by the teacher. On the basis of the audiotaped data, Gaies developed an inventory of learner verbal feedback consisting of 4 basic categories (responding, soliciting, reacting, and structuring) and 19 subcategories. Of interest here are Gaies’ findings that 1) learners used a variety of kinds of feedback, with reacting moves being the most frequent and structuring moves the least frequent, and 2) learners varied considerably in the amount of feedback they provided. In another study of non-native talk in small-group work, this time in a classroom setting, Pica and Doughty (in press) compared teacher-fronted discussions and small-group discussions on (oneway) decision-making tasks. Their data were taken from three classroom discussions and three small- group discussions (four students per group) involving low-intermediate-level ESL students. Their findings on grammaticality and amount of speech are similar to those of Porter (1983). Pica and Doughty found that student production, as measured by the percentage of grammatical T-units (Hunt 1970) per total number of T-units, was equally grammatical in the two contexts. In other words, students did not pay closer attention to their speech in the teacher’s presence. In terms of the amount of speech, Pica and Doughty found that the individual students talked more in their groups than in their teacher-fronted discussions, confirming previous findings of a clear advantage for group work in this area. Pica and Doughty also examined various interfactional features in the discussions. They found a very low frequency of comprehension and confirmation checks and clarification requests in both contexts and pointed out that such interfactional negotiation is not necessarily useful input for the entire class, as it is usually directed by and at individual students. In the teacher-led context, it serves only as a form of exposure for other class members, who may or may not be listening, whereas such negotiated input directed at a learner in a small group is far more likely to be useful for that learner. Finally, an examination of other-corrections and completions showed those features to be more typical of group work than of teacher-led discussions, thus supporting the arguments for learners’ conversational competence made by Porter and by Varonis and Gass. In a follow-up study, Doughty and Pica (1984) compared language use in teacher-fronted lessons, group work (four students per group), and pair work on a two-way task. The participants, who had the same level of proficiency as those in Pica and Doughty (in press), had to give and obtain information about how flowers were to be planted in a garden. Each started with an individual felt board displaying a different portion of a master plot. At the end of the activity, all participants were supposed to have constructed the same picture, which they compared against the master version then shown to them for the first time. The researchers compared their findings with those from their earlier study, in which a one-way task had been used. Doughty and Pica found that the two-way task generated significantly more negotiation work than the one-way task in the smallgroup setting but found no effect for task type in the teacher-led lessons. Negotiation was defined as the percentage of “conversational adjustments”; these adjustments included clarification requests, confirmation checks, comprehension checks, self- and other repetitions (both exact and semantic), over the total number of T-units and fragments. Clarification requests, confirmation checks, and comprehension checks, in particular, increased in frequency (from a total of 6 percent to 24 percent of all T-units and fragments in the small groups) with the switch to a two-way task in the second study. When task type was held constant, Doughty and Pica found that significantly more negotiation work (again measured by the ratio of conversational adjustments to total T-units and fragments) occurred in the small group (66 percent) and in pair work (68 percent) than in the lockstep format (45 percent), but that the difference in amounts between the small group and pair work was not statistically significant. 16

- 17. More total talk was generated in teacher-fronted lessons than in small groups on both types of task, and more total talk on two-way than on one-way tasks in both teacher-fronted and small-group discussions. However, the 33 percent increase in the amount of talk in the small groups for the two- way task was six times greater than the 5 percent increase provided by the two-way task in teacher- led lessons. Teacher-fronted lessons on a two-way task generated the most language use, and small- group discussion on a one-way task produced the least. As Doughty and Pica noted, however, the high total output in the teacher-fronted, one-way discussions was largely achieved by close to 50 percent of the talk being produced by the teachers, whereas teachers could not and did not dominate in this way on the garden-planting (two-way) task. Thus, students talked more on the two-way task, whether working with their teachers or in the four-person groups. Doughty and Pica also noted that negotiation work as a percentage of total talk was lower in teacher- fronted lessons on both oneway and two-way tasks. This finding, they suggested, may indicate that students are reluctant to indicate a lack of understanding in front of their teacher and an entire class of students and for that reason do not negotiate as much comprehensible input in wholeclass settings. This suggestion was supported by the researchers’ informal assessment of students’ actual comprehension, as judged by their lower success rate on the garden-planting task in the teacher-led than in the small-group discussions. Doughty and Pica concluded by emphasizing the importance not of group work per se, but of the nature of the task which the teacher provides for work done in small groups. Finally, two nonquantitative studies have contributed insights into interlanguage talk. Bruton and Samuda (1980) studied errors and error treatment in small-group discussions based on various problem solving tasks. Their learners were adults from a variety of language backgrounds, studying in an intensive course. The main findings were that 1) learners were capable of correcting each other successfully, even though their teachers had not instructed them to do so, and 2) learners were able to employ a variety of different error treatment strategies, among which were the offering of straight alternatives (i. e., explicit corrections) and the use of repair questions. In general, the learners’ treatments were much like those of their teachers, except that the most frequent errors treated by the learners were lexical items, not syntax or pronunciation. Bruton and Samuda also noted that in ten hours of observation, only once was a correct item changed to an incorrect one by a peer; furthermore, students did not pick up many errors from each other, a finding also reported by Porter (1983). Bruton and Samuda make the point that while learners seemed able to deal with apparent, immediate breakdowns in communication, several other, more subtle types of breakdown occurred which the students did not (and probably could not) treat. They suggest that learners be given an explanation of the various kinds of communication breakdowns that can occur, that they be taught strategies for coping with them, and that they be given explicit error-monitoring tasks during group work. Somewhat related to this work on error treatment is the analysis by Morrison and Low (1983) of monitoring in non-native discussions. Morrison and Low point out that their subjects, in addition to monitoring their own speech, self- correcting for lexis, syntax, discourse, and truth value without feedback from others and in a highly communicative context, also monitored the output of their interlocutors. This interactive view of monitoring, of making the struggle to communicate “a kind of team effort” includes the kind of negotiation that Varonis and Gass are describing. The transcripts presented by Morrison and Low, however, show a wide divergence in the extent to which groups pay attention to and provide feedback on their members’ speech. While some groups seemed to be involved in the topic and helped each other out at every lapse, other groups appeared totally absorbed in their own thoughts and inattentive to the speaker’s struggles to communicate. Summary of Research Findings The research findings reviewed above appear to support the following claims: Quantity Of Practice Students receive significantly more individual language practice opportunities in group work than in lockstep lessons (Long, Adams, McLean, and Castaños 1976, Doughty and Pica 1984, Pica and Doughty in press). They also receive significantly more practice opportunities in NNS/ NNS than in NS/NNS dyads (Porter 1983), more when the other NNS has greater rather than equal proficiency in the SL (Porter 1983), and more in two-way than in one-way tasks (Doughty and Pica 1984). 17

- 18. Variety Of Practice The range of language functions (rhetorical, pedagogic, and interpersonal) practiced by individual students is wider in group work than in lockstep teaching (Long, Adams, McLean, and Castaños 1976). Accuracy Of Student Production Students perform at the same level of grammatical accuracy in their SL output in unsupervised group work as in “public” lockstep work conducted by the teacher (Pica and Doughty in press). Similarly, the level of accuracy is the same whether the interlocutor in a dyad is a native or a non-native speaker (Porter 1983). Correction The frequency of other-correction and completions by students is higher in group work than in lockstep teaching (Pica and Doughty in press) and is not significantly different with NS and NNS interlocutors in small-group work, being very low in both contexts (Porter 1983). There seems to be considerable individual variability in the amount of attention students pay to their own and others’ speech (Gaies 1983b, Morrison and Low 1983), however, and some indication that training students to correct each other can help remedy this (Bruton and Samuda 1980). During group work, learners seem more apt to repair lexical errors, whereas teachers pay an equal amount of attention to errors of syntax and pronunciation (Bruton and Samuda 1980). Learners almost never miscorrect during unsupervised group work (Bruton and Samuda 1980, Porter 1983). Negotiation Students engage in more negotiation for meaning in the small group than in teacher- fronted, whole-class settings (Doughty and Pica 1984). NNS/NNS dyads engage in as much or more negotiation work than NS/NNS dyads (Porter 1983, Varonis and Gass 1983). In small groups, learners negotiate more with other learners who are at a different level of SL proficiency (Porter 1983, Varonis and Gass 1983) and more with learners from different first language backgrounds (Varonis and Gass 1983). Task Previous work on NS/NNS conversation has found two-way tasks to produce significantly more negotiation work than one-way tasks (Long 1980, 1981). The findings for interlanguage talk have been less clear, with one study (Gass and Varonis in press) not finding this pattern and another (Pica and Doughty in press) appearing not to do so, but actually not employing a genuine twoway task. The latest study of this issue (Doughty and Pica 1984), which did use a two-way task, that is, one requiring information exchange by both or all parties, supports the original claim for the importance of task type, with the two-way task significantly increasing the amount of talk, the amount of negotiation work, and—to judge impressionistically—the level of input comprehended by students, as measured by their task achievement. Finally, it seems that familiarity with a task decreases the amount of negotiation work it produces (Gass and Varonis in press). Implications for the Classroom The research findings on interlanguage talk generally support the claims commonly made for group work. Increases in the amount and variety of language practice available through group work are clearly two of its most attractive features, and these have obvious appeal to teachers of almost any methodological persuasion. The fact that the level of accuracy maintained in unsupervised groups has been found to be as high as that in teacher-monitored, lockstep work should help to allay fears that lower quality is the price to be paid for higher quantity of practice. The same is true of the findings that monitoring and correction occur spontaneously (although variably) in group work and that it seems possible to improve both through student training in correction techniques, if that is thought desirable. The apparently spontaneous occurrence of other-correction probably diminishes the importance sometimes attached to designation of one student in each group as leader, with special responsibility for monitoring accuracy. However, group leaders may still be needed for other reasons, such as ensuring that a task is carried out in the manner the teacher or materials writer intended. (See Long 1977 for further details concerning the logistics of organizing group work in the classroom) For many teachers, of course, concern about errors occurring and/or going uncorrected has diminished in recent years, since second language acquisition research has shown errors to be an inevitable, even “healthy,” part of language development. In fact, some teachers have been persuaded by theories of second language acquisition, such as Krashen’s (1982) Monitor Theory, and/or by new teaching methods, such as the Natural Approach (Krashen and Terrell 1983), to focus exclusively on communicative language use from the very earliest stages of instruction. Many others, while not abandoning attention to form altogether, are eager to ensure that their lessons contain sizable portions of communication work, even though this will inevitably involve errors. 18

- 19. For such teachers, the most interesting findings of the research on interlanguage talk do not concern quantity and variety of language practice or accuracy and correction, but rather, the negotiation work in NNS/NNS conversation. The findings of each of five studies which have looked at the issue of whether learners can accomplish as much or more of this kind of practice working together as with a NS are very encouraging. The related finding that students of mixed SL proficiencies tend to obtain more practice in negotiation than same-proficiency dyads suggests that when students with the same needs are working in small groups on the same materials or tasks, teachers of mixed-ability classes would do well to opt for heterogeneous (over homogeneous) ability grouping, unless additional considerations dictate otherwise. The fact that groups of mixed native language backgrounds tend to achieve greater amounts of negotiation also suggests grouping of students of mixed language backgrounds together where possible. For many teachers of multilingual classes, this would in any case be preferable, since it is one means of avoiding the development of “classroom dialects” intelligible only to speakers of a common first language—a phenomenon also avoidable through students having access to speakers of other target language varieties in lockstep work or outside the classroom. The finding concerning mixed first language groups does not mean, of course, that group work will be unsuccessful in monolingual classrooms, which is the norm in many EFL situations. To reiterate, the research shows clearly that the kind of negotiation work of interest here is also very successfully obtained in groups of students of the same first language background. Things simply seem slightly better with mixed language groups. Finally, the findings of research to date on interlanguage talk offer mixed evidence for the claimed advantages of two-way over oneway tasks in NS-NNS conversation. However, recent work on this issue seems to indicate that the claims are probably justified in the NNS-NNS context, too. Further, it appears to be the combination [of small-group work (including pair work) with two-way tasks] that is especially beneficial to learners in terms of the amount of talk produced, the amount of negotiation work produced, and the amount of comprehensible input obtained. In this light, teachers might think it desirable to include as many two-way tasks as possible among the activities students carry out in small groups. It is obviously useful to have students work on oneway tasks, such as telling a story which the listener does not know or describing a picture which the listener attempts to draw on the basis of the description alone. However, because one participant starts with all the information in such tasks, the other group members have nothing to “bargain” with; this limits the ability of the latter to negotiate the way the conversation develops. (Some one-way tasks in fact become monologues rather than conversations.) In conclusion, it should be remembered that group work is not a panacea. Teacher-fronted work is obviously useful for certain kinds of classroom activities, and poorly conceived or organized group work can be as ineffective as badly run lockstep lessons. Furthermore, additional information is still needed on such issues as the optimum size, composition, and internal organization of groups; about the structuring and management of tasks to be done in groups; and about the relationship between group work and teacher-led instruction. Despite these caveats, the authors are encouraged by the initial findings of what we hope will develop into a coherent and cumulative line of classroom-oriented research: studies of interlanguage talk. Together with theoretical advances concerning the role of input in second language acquisition, the studies we have reviewed have already contributed a psycholinguistic rationale to the existing pedagogical arguments for group work in the SL classroom. 19

- 20. ERIC Digest Identifier: ED427556. Publication Date: 1998-12-00 Authors: Moss, Donna - Van Duzer, Carol Source: National Clearinghouse for ESL Literacy Education - Washington DC. Digest Edited by: Tweedie, W.M. Project-Based Learning for Adult English Language Learners Project-based learning is an instructional approach that contextualizes learning by presenting learners with problems to solve or products to develop. For example, learners may research an aspect of one of their hobbies or their environments and create a report or handbook to share with other language learners in their program, or they might interview local citizens and create a bar graph mapping responses to questions quantitatively or qualitatively. This digest provides a rationale for using project-based learning with young English language learners, describes the process, and gives examples that demonstrate how the staff of an adult English as a Second Language (ESL) program has used project-based learning with their adult learners at varying levels of English proficiency. RATIONALE FOR PROJECT-BASED LEARNING Project-based learning functions as a bridge between using English in class and using English in real life situations outside of class (Fried-Booth, 1997). It does this by placing learners in situations that require authentic use of language in order to communicate (e.g., being part of a team or interviewing others). When learners work in pairs or in teams, they find they need skills to plan, organize, negotiate, make their points, and arrive at a consensus about issues such as what tasks to perform, who will be responsible for each task, and how information will be researched and presented. These skills have been identified by learners as important for living successful lives (Stein, 1995) and by employers as necessary in a high-performance workplace (U.S. Department of Labor, 1991). Because of the collaborative nature of project work, development of these skills occurs even among learners at low levels of language proficiency. Within the group work integral to projects, individuals' strengths and preferred ways of learning (e.g., by observing, reading, writing, listening, or speaking) strengthen the work of the team as a whole (Lawrence, 1997). Project-based learning is particularly applicable in the context of Technological Universities where practice and the practical application of knowledge acquired is given significant weight (70% of class time) in the curriculums of all career departments. This article and the work of the Editor (The PRIME Approach and Curriculum) justify the inclusion of project work in the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Programmes developed by the Editor for the Technological Universities of Mexico. THE PROCESS OF PROJECT-BASED WORK The basic phases found in most projects include: A. selecting a topic B. making plans C. researching D. developing products, and E. sharing results with others (reporting) (Wrigley, 1998) However, because project-based learning often hinges on group effort, establishing a trusting, cooperative relationship before embarking on a full-fledged project is also necessary. Activities that 20

- 21. engage learners in communication tasks and in peer- and self-evaluation help create the proper classroom environment. Information gap activities (where the assignment can only be completed through sharing of the different information each learner contributes), learner-to-learner interviews, role plays, simulations, field trips, contact assignments outside of class, and process writing with peers, prepare learners for project work. "Selecting Topics" A project should reflect the interests and concerns of the learners. Teachers can begin determining project topics at the start of an instructional cycle by conducting a class needs assessment to identify topic areas and skills to be developed. As the teacher and learners talk about projects and get to know each other, new topics and issues may come to light that are appropriate for project learning (Theme Webbing in the PRIME Approach). Projects will focus on the objectives spanning several units. They may be limited to one or two classes and/or culminate in a final event (presentation or report). Whatever the project, learners need to be in on the decision making from the beginning (Moss, 1998). "Making Plans and Doing Research" Once a topic is selected, learners work on their own or together (depending on learning style and the nature of the project selected) to plan the project, conduct research, and develop their reports, presentations, or products. Learners with low language proficiency or little experience working as part of a team may require structure and support throughout the project. Pre-project activities that introduce problem-solving strategies, language for negotiation, and methods for developing plans are useful. Learners may also need practice in specific language skills to complete project tasks. For example, learners using interviews as an information gathering technique may need instruction and practice in constructing and asking questions as well as in taking notes. "Sharing Results with Others" Project results can be shared in a number of ways. Oral presentations can accompany written reports or products developed within the classroom or in other classes within the program. Project products can also be disseminated in the larger community, as in the case of English language learners from an adult program in New York City, whose project culminated in the creation and management of a cafe and catering business (Lawrence, 1997; Wrigley, 1998). ASSESSING PROJECT-BASED WORK Project-based work lends itself well to evaluation of both employability skills and language skills. Introducing learners to self-evaluation and peer evaluation prior to embarking on a large project is advisable. Learners can evaluate themselves and each other through role plays, learner-to-learner interviews, and writing activities. They can become familiar with completing evaluation forms related to general class activities, and they can write about their learning in weekly journals where they reflect on what they learned, how they felt about their learning, and what they need to continue to work on in the future. They can even identify what should be evaluated and suggest how to do it. Assessment can be done by teachers, peers, or oneself. Teachers can observe the skills and knowledge that learners use and the ways they use language during the project. Learners can reflect on their own work and that of their peers, how well the team works, how they feel about their work and progress, and what skills and knowledge they are gaining. Reflecting on work, checking progress, and identifying areas of strength and weakness are part of the learning process. (See Iverson, S. The Five Dimensions of Learning) Assessment can also be done through small-group discussion with guided questions. What did your classmates do very well in the project? Was there anything that needed improvement? What? Why? The ability to identify or label the learning that is taking place builds life- long learning skills. Questionnaires, checklists, or essays can help learners do this by inviting them to 21

- 22. reflect critically on the skills and knowledge they are gaining. In a New York City initiative using project-based learning with adult English language learners called Expanding Capacity in ESOL programs (EXCAP), assessment occurred daily in dialogue journals, checklists, and portfolios (Lawrence, 1997). EXAMPLES FROM THE FIELD At the Arlington Education and Employment Program (REEP) in Virginia, a team of teachers designed and implemented several projects for their students, ranging from literacy level to advanced pre- TOEFL. They developed a framework for projects including learning strategies and affective behaviors that have a positive effect on progress and language learning. These behaviors include risk taking; using technological, human, and material resources; and organizing materials (Van Duzer, 1994). The project followed the four purposes for literacy identified by the Equipped for the Future initiative of the National Institute for Literacy--to access information, voice ideas and opinions, act independently, and continue learning throughout life (Stein, 1995). The two projects described below, developed by REEP staff, illustrate the range and complexity of project work. In one group project, parents in a family literacy program and their elementary school children created a coloring and activity book of community information for families living in their neighborhood in Arlington, Virginia. All of the parents and children took part in brainstorming sessions. They selected information, text, and graphics topics for each page of the book and contributed to the creation of the pages. Parents in the intermediate level class managed the production of the book and researched the topics selected (e.g., immunization, school). The adult literacy class located addresses and phone numbers of local agencies that provide needed services and illustrated a shopping guide of local stores they liked. They also designed a page of emergency telephone numbers. The children worked on drawings and activity pages for children. When the book was completed, the families presented it to the principal of the local elementary school. Some of the families participated in a "Meet the Authors" day at the local library. Parents and children alike kept their work in portfolios and completed assessment questionnaires. They shared their evaluations with each other and explained why they evaluated themselves the way they did. The teachers evaluated the parents on language skills, team participation, and successful completion of tasks. In another project, learners in an advanced intensive ESL class worked in pairs to present a thirty- minute lesson to other classes in the program. They worked collaboratively to determine the needs of their audience, interview teachers, choose topics, conduct research, prepare lessons, practice, offer evaluations to other teams during the rehearsal phase, present their lessons, and evaluate the effort. Topics ranged from ways to get rid of cockroaches to how the local government works. Before the lesson planning began, learners identified lesson objectives and evaluation criteria. They shared ideas on what makes a presentation successful, considering both language and presentation skills. The evaluation criteria used for feedback on rehearsals as well as for final evaluations include the following: Introduces self and the topic clearly, respectfully, and completely. Includes interactive activities in the lesson. Speaks in a way that is easy to understand. Is responsive to the audience. 22