HUM40-Podcast-F11-W2

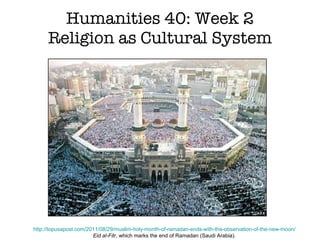

- 1. Humanities 40: Week 2 Religion as Cultural System http://topusapost.com/2011/08/29/muslim-holy-month-of-ramadan-ends-with-the-observation-of-the-new-moon/ Eid al-Fitr , which marks the end of Ramadan (Saudi Arabia).

- 3. BEFORE FRIDAY READ/WATCH: Interview with Robert Bellah, “Rethinking Secularism in a Global Age” Post “explanation” or “theory” of religion.

- 5. THE BIG PICTURE: SAMPLE BLOGS (Student Responses)

- 6. Sample Definitions of Religion

- 7. “ The religious response is a response to experience and is coloured by the wish to provide a wider context for a fragile, short and turbulent life.” – Philip Rousseau

- 8. A powerful system that tries to explain the unexplainable.

- 9. A belief system and way of life which include certain rituals, practices, or moral codes.

- 10. A lifestyle choice, a strong connection with a certain spiritual figure that you look to in order to answer life’s hard questions.

- 11. How does Jerome Bruner’s model of human development ( enactive, iconic, and symbolic forms of representation ) relate to the practice of religion? BURNING QUESTION 1

- 12. How does [any model] of human development relate to the practice of religion? DEEPER QUESTION

- 13. How does the practice of religion follow the process of human development cross-culturally? EVEN DEEPER QUESTION

- 14. What are the differences between substantive and functionalist definitions of religion? REVIEW QUESTION 1

- 15. Describe at least two dimensions of religion you’ve experienced or witnessed in the last year. Share with your classmate. REVIEW QUESTION 2

- 16. Do you think America would be the Supreme Power of the world had it not been for the combination of Christianity and Government ? BURNING QUESTION 2

- 17. Do you think China would be the Economic Power of the world had it not been for the combination of Communism, Global Capitalism, and Government ? ALTERNATIVE QUESTION

- 18. Do you think [any country] would be the [dominating force] of the world had it not been for the combination of [religious or non-religious beliefs] and [political structures] ? DEEPER QUESTION

- 19. In what ways do political nations or empires develop their power or systems of government from the religious (or non-religious) ideas and practices of their citizens (and leaders)? REFRAMED QUESTION

- 20. In what ways do religion and politics (or other institutions) influence each other? DEEPER QUESTION

- 21. SUGGESTED TEXT

- 22. REVIEW

- 23. 1. Religion is a cultural system. 2. Religion is best understood as a vernacular practice (as lived). Two propositions

- 25. The “Reality” of Religion sacred profane gray area religion “ reality”

- 36. Seven Dimensions of the Sacred

- 37. sacred: regarded with great respect or reverence by an individual or group

- 38. sacred: induces experiences of awe and wonder

- 39. wonder: a feeling of surprise mingled with admiration, caused by something beautiful, unexpected, unfamiliar, or inexplicable

- 49. Seven Dimensions of the Sacred: Two Examples

- 52. CLIFFORD GEERTZ Religion as Cultural System

- 54. RODNEY STARK and WILLIAM BAINBRIDGE Religion as Compensator

- 55. RODNEY STARK and WILLIAM BAINBRIDGE RATIONAL-CHOICE THEORY

- 56. RODNEY STARK and WILLIAM BAINBRIDGE Religion is made up of practices that “reward” an individual or group for some physical lack or frustrated goal.

- 57. Rituals a series of repeated actions or behaviors that are regularly followed by an individual or group

- 58. Rituals often agreed-upon, formalized patterns of movements carried out in particular contexts

- 59. Rituals employ powerful symbols and engage the body through multiple senses

- 60. Rites of Passage life-cycle rituals: birth, childhood, coming-of-age, marriage, death

- 61. Rites of Passage transitional periods that culturally mark a change from one stage of life to another

- 66. Graduation Ceremony (San Diego City College, 2008) What happens during graduation? Why?

- 67. Young monks in training (Burma) What are the ages and genders of these participants? How are they dressed? How are their bodies positioned?

- 69. Navjote Ceremony (Parsi community, India)

- 70. Fulbe boys (northern Cameroon)

- 73. Papua New Guinea (Sepik River)

- 74. Samoan Gangs (Long Beach, CA)

- 75. Samoan Gangs (Long Beach, CA)

- 76. U.S. Marine recruits (“jarheads”)

- 77. Crossing the Equator (U.S. Navy)

- 78. CASE STUDY: Apache Girls (Sunrise Ceremony) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5B3Abpv0ysM

Notas del editor

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- (for Benjamin, this quality surrounds the "original" work of art, and provides it with a sense of unreproducible "authenticity")

- Seattle Public Library

- Why do people believe in different ideas? Why is there so much religious conflict? What the relationship between science and religion? Can change happen?

- Émile Durkheim (1858−1917)—author of The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)—and others thought that Aboriginal groups provided a lens into the most basic forms of religious behavior. 1. Durkheim identified the primary force behind religion as the sacred and argued that the sacred serves as a mirror of a particular society. A society holds up symbols so that, in effect, it can worship itself and propagate its value system. 2. Durkheim viewed religion as an expression of social cohesion in human societies.

- Émile Durkheim (1858−1917)—author of The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)—and others thought that Aboriginal groups provided a lens into the most basic forms of religious behavior. 1. Durkheim identified the primary force behind religion as the sacred and argued that the sacred serves as a mirror of a particular society. A society holds up symbols so that, in effect, it can worship itself and propagate its value system. 2. Durkheim viewed religion as an expression of social cohesion in human societies.

- Émile Durkheim (1858−1917)—author of The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)—and others thought that Aboriginal groups provided a lens into the most basic forms of religious behavior. 1. Durkheim identified the primary force behind religion as the sacred and argued that the sacred serves as a mirror of a particular society. A society holds up symbols so that, in effect, it can worship itself and propagate its value system. 2. Durkheim viewed religion as an expression of social cohesion in human societies.

- Émile Durkheim (1858−1917)—author of The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)—and others thought that Aboriginal groups provided a lens into the most basic forms of religious behavior. 1. Durkheim identified the primary force behind religion as the sacred and argued that the sacred serves as a mirror of a particular society. A society holds up symbols so that, in effect, it can worship itself and propagate its value system. 2. Durkheim viewed religion as an expression of social cohesion in human societies.

- Émile Durkheim (1858−1917)—author of The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)—and others thought that Aboriginal groups provided a lens into the most basic forms of religious behavior. 1. Durkheim identified the primary force behind religion as the sacred and argued that the sacred serves as a mirror of a particular society. A society holds up symbols so that, in effect, it can worship itself and propagate its value system. 2. Durkheim viewed religion as an expression of social cohesion in human societies.

- Émile Durkheim (1858−1917)—author of The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)—and others thought that Aboriginal groups provided a lens into the most basic forms of religious behavior. 1. Durkheim identified the primary force behind religion as the sacred and argued that the sacred serves as a mirror of a particular society. A society holds up symbols so that, in effect, it can worship itself and propagate its value system. 2. Durkheim viewed religion as an expression of social cohesion in human societies.

- Eliade suggests that at the heart of religious experience is human awareness of the sacred. He argued that the sacred is made known through heirophanies (manifestations of the sacred) and theophanies (manifestations of God). When people perceive a manifestation of the sacred, everything changes—objects, people, places, and even time. A theophany is a manifestation of God. 1. Moses encountered God and received the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. 2. When Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River, the sky opened, a dove descended, and God’s resounding voice declared, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased!” 3. At a pivotal moment in the Bhagavad Gita, a dialogue takes place between Arjuna (a warrior about to go into battle, who is the focus of the Bhagavad Gita) and his chariot driver. The chariot driver reveals himself as Krishna, the incarnation of the Lord Vishnu. 4. From the Islamic tradition comes the time when, during an interlude of prayer and meditation, Muhammad was first called to be a prophet. A hierophany is a broader category indicating a manifestation of the sacred. For example, according to Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha Gautama was conceived during a miraculous vision by his mother and was born through her side as flowers bloomed out of season. Sages appeared to visit the newborn and make prophecies about his auspicious career. Sacred time is a universal category in the religions. 1. Easter Sunday is the most sacred day in the Christian calendar. Sunday, then, became the sacred day of the week—a shift from the Jewish Sabbath that starts Friday evening and lasts until sundown Saturday. 2. Muslims are required to fast and refrain from all pleasurable activities from sunrise until sunset throughout the sacred lunar month of Ramadan each year. 3. For Jews, the most holy day of the year is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Traditionally, Yom Kippur is understood as the date on which Moses received the Ten Commandments for the second time. 4. The Hindu festival of Holi is celebrated each spring; devotees imitate Krishna’s frivolous play with the gopis (cowherds’ wives).

- Eliade suggests that at the heart of religious experience is human awareness of the sacred. He argued that the sacred is made known through heirophanies (manifestations of the sacred) and theophanies (manifestations of God). When people perceive a manifestation of the sacred, everything changes—objects, people, places, and even time. A theophany is a manifestation of God. 1. Moses encountered God and received the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. 2. When Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River, the sky opened, a dove descended, and God’s resounding voice declared, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased!” 3. At a pivotal moment in the Bhagavad Gita, a dialogue takes place between Arjuna (a warrior about to go into battle, who is the focus of the Bhagavad Gita) and his chariot driver. The chariot driver reveals himself as Krishna, the incarnation of the Lord Vishnu. 4. From the Islamic tradition comes the time when, during an interlude of prayer and meditation, Muhammad was first called to be a prophet. A hierophany is a broader category indicating a manifestation of the sacred. For example, according to Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha Gautama was conceived during a miraculous vision by his mother and was born through her side as flowers bloomed out of season. Sages appeared to visit the newborn and make prophecies about his auspicious career. Sacred time is a universal category in the religions. 1. Easter Sunday is the most sacred day in the Christian calendar. Sunday, then, became the sacred day of the week—a shift from the Jewish Sabbath that starts Friday evening and lasts until sundown Saturday. 2. Muslims are required to fast and refrain from all pleasurable activities from sunrise until sunset throughout the sacred lunar month of Ramadan each year. 3. For Jews, the most holy day of the year is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Traditionally, Yom Kippur is understood as the date on which Moses received the Ten Commandments for the second time. 4. The Hindu festival of Holi is celebrated each spring; devotees imitate Krishna’s frivolous play with the gopis (cowherds’ wives).

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto)

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc. Ethnic sculpture and fugurines of the Jhakri culture. Jhakris in healing Ritual of sick person. Shamans/Jhakris get into a trace by singing, dancing, taking entheogens, meditating and drumming.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto) Torah, legal imperatives; Shari’a; Buddhism: four great virtues; Confucianism: morality: the ideal investment in human behavior. Religious specialists or priests: gurus, lawyers, pastors, rabbis, imams, shamans, etc.) Sacred sites of worship: chapels, cathedrals, temples, mosques, icons, books, pulpits, monasteries, etc.

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto)

- Worship, Meditation, Pilgrimage, Sacrifice, Rites, and Healing. Example: impermanence (Buddhism); Original Sin (Christianity); interact with previous dimensions; some more strict or rigid than others: e.g., Catholicism more than Quakerism, Buddhism more than African religions, Theravada more than Zen. Stories: Christ’s life, death, and resurrection; Buddha’s life; Muhammad’s life; “founders” of religion. Secular examples: “history” instead of “myth”; history taught in schools is major generator of “national” identity; it enhances pride in our ancestors, our national heroes and heroines Examples: enlightenment of the Buddha, prophetic visions of Muhammad, conversion of Paul, etc. The Vision Quest: Zen, Native American classical religion, the idea of the “holy” (Otto)

- Eliade suggests that at the heart of religious experience is human awareness of the sacred. He argued that the sacred is made known through heirophanies (manifestations of the sacred) and theophanies (manifestations of God). When people perceive a manifestation of the sacred, everything changes—objects, people, places, and even time. A theophany is a manifestation of God. 1. Moses encountered God and received the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. 2. When Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River, the sky opened, a dove descended, and God’s resounding voice declared, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased!” 3. At a pivotal moment in the Bhagavad Gita, a dialogue takes place between Arjuna (a warrior about to go into battle, who is the focus of the Bhagavad Gita) and his chariot driver. The chariot driver reveals himself as Krishna, the incarnation of the Lord Vishnu. 4. From the Islamic tradition comes the time when, during an interlude of prayer and meditation, Muhammad was first called to be a prophet. A hierophany is a broader category indicating a manifestation of the sacred. For example, according to Buddhist tradition, Siddhartha Gautama was conceived during a miraculous vision by his mother and was born through her side as flowers bloomed out of season. Sages appeared to visit the newborn and make prophecies about his auspicious career. Sacred time is a universal category in the religions. 1. Easter Sunday is the most sacred day in the Christian calendar. Sunday, then, became the sacred day of the week—a shift from the Jewish Sabbath that starts Friday evening and lasts until sundown Saturday. 2. Muslims are required to fast and refrain from all pleasurable activities from sunrise until sunset throughout the sacred lunar month of Ramadan each year. 3. For Jews, the most holy day of the year is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Traditionally, Yom Kippur is understood as the date on which Moses received the Ten Commandments for the second time. 4. The Hindu festival of Holi is celebrated each spring; devotees imitate Krishna’s frivolous play with the gopis (cowherds’ wives).

- The rational choice theory has been applied to religions, among others by the sociologists Rodney Stark (1934 – ) and William Sims Bainbridge (1940 – ).[59] They see religions as systems of "compensators".[60] Compensators are a body of language and practices that compensate for some physical lack or frustrated goal. They can be divided into specific compensators (compensators for the failure to achieve specific goals), and general compensators (compensators for failure to achieve any goal).[60][61] They define religion as a system of compensator that relies on the supernatural.[62] They assert that only a supernatural compensator can explain death or the meaning of life.[62]

- The rational choice theory has been applied to religions, among others by the sociologists Rodney Stark (1934 – ) and William Sims Bainbridge (1940 – ).[59] They see religions as systems of "compensators".[60] Compensators are a body of language and practices that compensate for some physical lack or frustrated goal. They can be divided into specific compensators (compensators for the failure to achieve specific goals), and general compensators (compensators for failure to achieve any goal).[60][61] They define religion as a system of compensator that relies on the supernatural.[62] They assert that only a supernatural compensator can explain death or the meaning of life.[62]

- The rational choice theory has been applied to religions, among others by the sociologists Rodney Stark (1934 – ) and William Sims Bainbridge (1940 – ).[59] They see religions as systems of "compensators".[60] Compensators are a body of language and practices that compensate for some physical lack or frustrated goal. They can be divided into specific compensators (compensators for the failure to achieve specific goals), and general compensators (compensators for failure to achieve any goal).[60][61] They define religion as a system of compensator that relies on the supernatural.[62] They assert that only a supernatural compensator can explain death or the meaning of life.[62]

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret From Birth to Death—Religious Rituals Scope: Rituals are a central feature in human society. We all participate in a variety of ritual activities all the time—from the protocol involved in greeting one another or the playing of the national anthem before sporting events to graduation or initiation rituals. In both secular and religious contexts, we can identify two major types of rituals: those based on the lifecycle and those based on the calendar. This lecture explores the common features of religious rituals that mark key stages in the lifecycle: birth, childhood, coming-of-age, marriage, and death. Rituals embody obligatory and repetitive components charged with symbolism; they are dramatic, engaging all the senses; and they are necessary to change the participants’ life status permanently. Lifecycle rituals in all religions encompass three distinct stages: separation, transition, and reincorporation. In this lecture, we find examples of these stages in baptism, Bar or Bat Mitzvah, marriage, Buddhist and Christian ordination, and funeral rituals. Outline I. Rituals are a central feature of human life, both individually and in community. Rituals are a prescribed set of actions that often employ powerful symbols to accomplish both religious and secular purposes. A. People in all cultures participate in rituals based on both the human lifecycle and the calendar. 1. In the United States, secular lifecycle rituals include graduation from high school, a swearing-in ceremony for a public official, initiation into a fraternity or sorority, a celebration on reaching the age of 21, and so on. 2. Common secular calendar rituals in the United States include such activities as reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to start the day at public school, ritual traditions around Thanksgiving, and birthday celebrations. B. James Livingston defines a religious ritual as “an agreed-upon, formalized pattern of ceremonial movements and actions carried out in a sacred context.” We will examine common features of both religious lifecycle and calendar rituals in this and the next lecture. C. Rituals share several common elements. The words, actions, and symbols are repetitive and obligatory, and they engage multiple senses in the process of accomplishing specific goals. II. French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep identified three stages commonly found in lifecycle rite-of-passage rituals: separation, transition, and reincorporation. A brief consideration of the structure of a high school graduation ceremony illustrates the three stages. III. Religious lifecycle rituals occur one time (theoretically) during the course of an individual’s lifecycle. The major religions we are considering incorporate rituals to mark four stages in the human lifecycle: birth, coming of age, marriage, and death. In the rituals associated with these events, we can identify the three stages of separation, transition, and reincorporation. A. Religious rituals associated with birth welcome or initiate the new life into the community of faith. 1. In Judaism, males are circumcised on the eighth day after birth, according to the covenant given in the Book of Genesis. 2. Many Christian denominations—Catholics, Orthodox, and some Protestants (such as Lutherans and Presbyterians)—practice infant baptism. Others practice “dedication of babies” in the belief that the ritual of baptism should take place only after one has made an adult profession of faith. B. Religious coming-of-age rituals are often associated with physical maturation around the time of puberty. 1. The Hindu sacred thread ceremony ( upanayana) initiates boys into their new role as students who will learn the teachings and practices required of their religion. 2. A Jewish boy or girl becomes a “son/daughter of the Commandment” through the prescribed ritual known as Bar or Bat Mitzvah . From this point forward, the young man or woman must follow Jewish Law, tradition, and ethics and participate fully in all aspects of Jewish community life. C. Marriage rituals mark a new stage of life—socially and legally—as individuals formally leave their families to form new homes. 1. Christian marriage ceremonies follow prescribed patterns (instruction, vows) and incorporate many religious symbols and dramatic elements, such as special music and visual effects to appeal to the senses. 2. The ordination of a Buddhist monk or a Christian monk, nun, or priest who takes a vow of celibacy is a parallel form of commitment within the respective religions. D. Rituals associated with death mark the end of an individual’s lifecycle and provide powerful moments to educate the religious community about the meaning of life and the changing human community of faith. 1. Muslim funeral practices prescribe burial of the deceased before sundown of the day after death and emphasize equality before God with burial in simple garments. The body is placed facing in the direction of Mecca. 2. Jewish rituals also require burial before sundown of the day following death, with the grave close to Jerusalem, if possible, in preparation for the coming of the messiah on the day of resurrection. Relatives and close friends stay with the body until the time of burial. 3. The traditional Hindu practice of cremation is based on the belief that the soul does not enter another body until the original body is returned to the basic elements. 4. Buddhist practices vary a great deal. Tibetan Buddhists, for example, engage in a lengthy, intricate ritual to help the deceased make the proper transition into a blissful state. 5. Christian funeral rites include many of the same components of separation, transition, and reincorporation visible in other religions. Suggested Readings: Catherine Bell, ed., Teaching Ritual. Jean Holm and John Bowker, Rites of Passage. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage. Questions to Consider: 1. Identify and describe five or more religiously connected lifecycle rituals with which you have personally been involved. In what ways have these been stale and perfunctory? In what ways have they been powerful, engaging, and memorable events for you or those you have observed obtaining a new status through the ritual event? 2. What might the rituals marking major stages of the human lifecycle in the different religions suggest about commonality across religious lines? ©

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret From Birth to Death—Religious Rituals Scope: Rituals are a central feature in human society. We all participate in a variety of ritual activities all the time—from the protocol involved in greeting one another or the playing of the national anthem before sporting events to graduation or initiation rituals. In both secular and religious contexts, we can identify two major types of rituals: those based on the lifecycle and those based on the calendar. This lecture explores the common features of religious rituals that mark key stages in the lifecycle: birth, childhood, coming-of-age, marriage, and death. Rituals embody obligatory and repetitive components charged with symbolism; they are dramatic, engaging all the senses; and they are necessary to change the participants’ life status permanently. Lifecycle rituals in all religions encompass three distinct stages: separation, transition, and reincorporation. In this lecture, we find examples of these stages in baptism, Bar or Bat Mitzvah, marriage, Buddhist and Christian ordination, and funeral rituals. Outline I. Rituals are a central feature of human life, both individually and in community. Rituals are a prescribed set of actions that often employ powerful symbols to accomplish both religious and secular purposes. A. People in all cultures participate in rituals based on both the human lifecycle and the calendar. 1. In the United States, secular lifecycle rituals include graduation from high school, a swearing-in ceremony for a public official, initiation into a fraternity or sorority, a celebration on reaching the age of 21, and so on. 2. Common secular calendar rituals in the United States include such activities as reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to start the day at public school, ritual traditions around Thanksgiving, and birthday celebrations. B. James Livingston defines a religious ritual as “an agreed-upon, formalized pattern of ceremonial movements and actions carried out in a sacred context.” We will examine common features of both religious lifecycle and calendar rituals in this and the next lecture. C. Rituals share several common elements. The words, actions, and symbols are repetitive and obligatory, and they engage multiple senses in the process of accomplishing specific goals. II. French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep identified three stages commonly found in lifecycle rite-of-passage rituals: separation, transition, and reincorporation. A brief consideration of the structure of a high school graduation ceremony illustrates the three stages. III. Religious lifecycle rituals occur one time (theoretically) during the course of an individual’s lifecycle. The major religions we are considering incorporate rituals to mark four stages in the human lifecycle: birth, coming of age, marriage, and death. In the rituals associated with these events, we can identify the three stages of separation, transition, and reincorporation. A. Religious rituals associated with birth welcome or initiate the new life into the community of faith. 1. In Judaism, males are circumcised on the eighth day after birth, according to the covenant given in the Book of Genesis. 2. Many Christian denominations—Catholics, Orthodox, and some Protestants (such as Lutherans and Presbyterians)—practice infant baptism. Others practice “dedication of babies” in the belief that the ritual of baptism should take place only after one has made an adult profession of faith. B. Religious coming-of-age rituals are often associated with physical maturation around the time of puberty. 1. The Hindu sacred thread ceremony ( upanayana) initiates boys into their new role as students who will learn the teachings and practices required of their religion. 2. A Jewish boy or girl becomes a “son/daughter of the Commandment” through the prescribed ritual known as Bar or Bat Mitzvah . From this point forward, the young man or woman must follow Jewish Law, tradition, and ethics and participate fully in all aspects of Jewish community life. C. Marriage rituals mark a new stage of life—socially and legally—as individuals formally leave their families to form new homes. 1. Christian marriage ceremonies follow prescribed patterns (instruction, vows) and incorporate many religious symbols and dramatic elements, such as special music and visual effects to appeal to the senses. 2. The ordination of a Buddhist monk or a Christian monk, nun, or priest who takes a vow of celibacy is a parallel form of commitment within the respective religions. D. Rituals associated with death mark the end of an individual’s lifecycle and provide powerful moments to educate the religious community about the meaning of life and the changing human community of faith. 1. Muslim funeral practices prescribe burial of the deceased before sundown of the day after death and emphasize equality before God with burial in simple garments. The body is placed facing in the direction of Mecca. 2. Jewish rituals also require burial before sundown of the day following death, with the grave close to Jerusalem, if possible, in preparation for the coming of the messiah on the day of resurrection. Relatives and close friends stay with the body until the time of burial. 3. The traditional Hindu practice of cremation is based on the belief that the soul does not enter another body until the original body is returned to the basic elements. 4. Buddhist practices vary a great deal. Tibetan Buddhists, for example, engage in a lengthy, intricate ritual to help the deceased make the proper transition into a blissful state. 5. Christian funeral rites include many of the same components of separation, transition, and reincorporation visible in other religions. Suggested Readings: Catherine Bell, ed., Teaching Ritual. Jean Holm and John Bowker, Rites of Passage. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage. Questions to Consider: 1. Identify and describe five or more religiously connected lifecycle rituals with which you have personally been involved. In what ways have these been stale and perfunctory? In what ways have they been powerful, engaging, and memorable events for you or those you have observed obtaining a new status through the ritual event? 2. What might the rituals marking major stages of the human lifecycle in the different religions suggest about commonality across religious lines? ©

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret From Birth to Death—Religious Rituals Scope: Rituals are a central feature in human society. We all participate in a variety of ritual activities all the time—from the protocol involved in greeting one another or the playing of the national anthem before sporting events to graduation or initiation rituals. In both secular and religious contexts, we can identify two major types of rituals: those based on the lifecycle and those based on the calendar. This lecture explores the common features of religious rituals that mark key stages in the lifecycle: birth, childhood, coming-of-age, marriage, and death. Rituals embody obligatory and repetitive components charged with symbolism; they are dramatic, engaging all the senses; and they are necessary to change the participants’ life status permanently. Lifecycle rituals in all religions encompass three distinct stages: separation, transition, and reincorporation. In this lecture, we find examples of these stages in baptism, Bar or Bat Mitzvah, marriage, Buddhist and Christian ordination, and funeral rituals. Outline I. Rituals are a central feature of human life, both individually and in community. Rituals are a prescribed set of actions that often employ powerful symbols to accomplish both religious and secular purposes. A. People in all cultures participate in rituals based on both the human lifecycle and the calendar. 1. In the United States, secular lifecycle rituals include graduation from high school, a swearing-in ceremony for a public official, initiation into a fraternity or sorority, a celebration on reaching the age of 21, and so on. 2. Common secular calendar rituals in the United States include such activities as reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to start the day at public school, ritual traditions around Thanksgiving, and birthday celebrations. B. James Livingston defines a religious ritual as “an agreed-upon, formalized pattern of ceremonial movements and actions carried out in a sacred context.” We will examine common features of both religious lifecycle and calendar rituals in this and the next lecture. C. Rituals share several common elements. The words, actions, and symbols are repetitive and obligatory, and they engage multiple senses in the process of accomplishing specific goals. II. French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep identified three stages commonly found in lifecycle rite-of-passage rituals: separation, transition, and reincorporation. A brief consideration of the structure of a high school graduation ceremony illustrates the three stages. III. Religious lifecycle rituals occur one time (theoretically) during the course of an individual’s lifecycle. The major religions we are considering incorporate rituals to mark four stages in the human lifecycle: birth, coming of age, marriage, and death. In the rituals associated with these events, we can identify the three stages of separation, transition, and reincorporation. A. Religious rituals associated with birth welcome or initiate the new life into the community of faith. 1. In Judaism, males are circumcised on the eighth day after birth, according to the covenant given in the Book of Genesis. 2. Many Christian denominations—Catholics, Orthodox, and some Protestants (such as Lutherans and Presbyterians)—practice infant baptism. Others practice “dedication of babies” in the belief that the ritual of baptism should take place only after one has made an adult profession of faith. B. Religious coming-of-age rituals are often associated with physical maturation around the time of puberty. 1. The Hindu sacred thread ceremony ( upanayana) initiates boys into their new role as students who will learn the teachings and practices required of their religion. 2. A Jewish boy or girl becomes a “son/daughter of the Commandment” through the prescribed ritual known as Bar or Bat Mitzvah . From this point forward, the young man or woman must follow Jewish Law, tradition, and ethics and participate fully in all aspects of Jewish community life. C. Marriage rituals mark a new stage of life—socially and legally—as individuals formally leave their families to form new homes. 1. Christian marriage ceremonies follow prescribed patterns (instruction, vows) and incorporate many religious symbols and dramatic elements, such as special music and visual effects to appeal to the senses. 2. The ordination of a Buddhist monk or a Christian monk, nun, or priest who takes a vow of celibacy is a parallel form of commitment within the respective religions. D. Rituals associated with death mark the end of an individual’s lifecycle and provide powerful moments to educate the religious community about the meaning of life and the changing human community of faith. 1. Muslim funeral practices prescribe burial of the deceased before sundown of the day after death and emphasize equality before God with burial in simple garments. The body is placed facing in the direction of Mecca. 2. Jewish rituals also require burial before sundown of the day following death, with the grave close to Jerusalem, if possible, in preparation for the coming of the messiah on the day of resurrection. Relatives and close friends stay with the body until the time of burial. 3. The traditional Hindu practice of cremation is based on the belief that the soul does not enter another body until the original body is returned to the basic elements. 4. Buddhist practices vary a great deal. Tibetan Buddhists, for example, engage in a lengthy, intricate ritual to help the deceased make the proper transition into a blissful state. 5. Christian funeral rites include many of the same components of separation, transition, and reincorporation visible in other religions. Suggested Readings: Catherine Bell, ed., Teaching Ritual. Jean Holm and John Bowker, Rites of Passage. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage. Questions to Consider: 1. Identify and describe five or more religiously connected lifecycle rituals with which you have personally been involved. In what ways have these been stale and perfunctory? In what ways have they been powerful, engaging, and memorable events for you or those you have observed obtaining a new status through the ritual event? 2. What might the rituals marking major stages of the human lifecycle in the different religions suggest about commonality across religious lines? ©

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret From Birth to Death—Religious Rituals Scope: Rituals are a central feature in human society. We all participate in a variety of ritual activities all the time—from the protocol involved in greeting one another or the playing of the national anthem before sporting events to graduation or initiation rituals. In both secular and religious contexts, we can identify two major types of rituals: those based on the lifecycle and those based on the calendar. This lecture explores the common features of religious rituals that mark key stages in the lifecycle: birth, childhood, coming-of-age, marriage, and death. Rituals embody obligatory and repetitive components charged with symbolism; they are dramatic, engaging all the senses; and they are necessary to change the participants’ life status permanently. Lifecycle rituals in all religions encompass three distinct stages: separation, transition, and reincorporation. In this lecture, we find examples of these stages in baptism, Bar or Bat Mitzvah, marriage, Buddhist and Christian ordination, and funeral rituals. Outline I. Rituals are a central feature of human life, both individually and in community. Rituals are a prescribed set of actions that often employ powerful symbols to accomplish both religious and secular purposes. A. People in all cultures participate in rituals based on both the human lifecycle and the calendar. 1. In the United States, secular lifecycle rituals include graduation from high school, a swearing-in ceremony for a public official, initiation into a fraternity or sorority, a celebration on reaching the age of 21, and so on. 2. Common secular calendar rituals in the United States include such activities as reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to start the day at public school, ritual traditions around Thanksgiving, and birthday celebrations. B. James Livingston defines a religious ritual as “an agreed-upon, formalized pattern of ceremonial movements and actions carried out in a sacred context.” We will examine common features of both religious lifecycle and calendar rituals in this and the next lecture. C. Rituals share several common elements. The words, actions, and symbols are repetitive and obligatory, and they engage multiple senses in the process of accomplishing specific goals. II. French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep identified three stages commonly found in lifecycle rite-of-passage rituals: separation, transition, and reincorporation. A brief consideration of the structure of a high school graduation ceremony illustrates the three stages. III. Religious lifecycle rituals occur one time (theoretically) during the course of an individual’s lifecycle. The major religions we are considering incorporate rituals to mark four stages in the human lifecycle: birth, coming of age, marriage, and death. In the rituals associated with these events, we can identify the three stages of separation, transition, and reincorporation. A. Religious rituals associated with birth welcome or initiate the new life into the community of faith. 1. In Judaism, males are circumcised on the eighth day after birth, according to the covenant given in the Book of Genesis. 2. Many Christian denominations—Catholics, Orthodox, and some Protestants (such as Lutherans and Presbyterians)—practice infant baptism. Others practice “dedication of babies” in the belief that the ritual of baptism should take place only after one has made an adult profession of faith. B. Religious coming-of-age rituals are often associated with physical maturation around the time of puberty. 1. The Hindu sacred thread ceremony ( upanayana) initiates boys into their new role as students who will learn the teachings and practices required of their religion. 2. A Jewish boy or girl becomes a “son/daughter of the Commandment” through the prescribed ritual known as Bar or Bat Mitzvah . From this point forward, the young man or woman must follow Jewish Law, tradition, and ethics and participate fully in all aspects of Jewish community life. C. Marriage rituals mark a new stage of life—socially and legally—as individuals formally leave their families to form new homes. 1. Christian marriage ceremonies follow prescribed patterns (instruction, vows) and incorporate many religious symbols and dramatic elements, such as special music and visual effects to appeal to the senses. 2. The ordination of a Buddhist monk or a Christian monk, nun, or priest who takes a vow of celibacy is a parallel form of commitment within the respective religions. D. Rituals associated with death mark the end of an individual’s lifecycle and provide powerful moments to educate the religious community about the meaning of life and the changing human community of faith. 1. Muslim funeral practices prescribe burial of the deceased before sundown of the day after death and emphasize equality before God with burial in simple garments. The body is placed facing in the direction of Mecca. 2. Jewish rituals also require burial before sundown of the day following death, with the grave close to Jerusalem, if possible, in preparation for the coming of the messiah on the day of resurrection. Relatives and close friends stay with the body until the time of burial. 3. The traditional Hindu practice of cremation is based on the belief that the soul does not enter another body until the original body is returned to the basic elements. 4. Buddhist practices vary a great deal. Tibetan Buddhists, for example, engage in a lengthy, intricate ritual to help the deceased make the proper transition into a blissful state. 5. Christian funeral rites include many of the same components of separation, transition, and reincorporation visible in other religions. Suggested Readings: Catherine Bell, ed., Teaching Ritual. Jean Holm and John Bowker, Rites of Passage. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage. Questions to Consider: 1. Identify and describe five or more religiously connected lifecycle rituals with which you have personally been involved. In what ways have these been stale and perfunctory? In what ways have they been powerful, engaging, and memorable events for you or those you have observed obtaining a new status through the ritual event? 2. What might the rituals marking major stages of the human lifecycle in the different religions suggest about commonality across religious lines? ©

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret From Birth to Death—Religious Rituals Scope: Rituals are a central feature in human society. We all participate in a variety of ritual activities all the time—from the protocol involved in greeting one another or the playing of the national anthem before sporting events to graduation or initiation rituals. In both secular and religious contexts, we can identify two major types of rituals: those based on the lifecycle and those based on the calendar. This lecture explores the common features of religious rituals that mark key stages in the lifecycle: birth, childhood, coming-of-age, marriage, and death. Rituals embody obligatory and repetitive components charged with symbolism; they are dramatic, engaging all the senses; and they are necessary to change the participants’ life status permanently. Lifecycle rituals in all religions encompass three distinct stages: separation, transition, and reincorporation. In this lecture, we find examples of these stages in baptism, Bar or Bat Mitzvah, marriage, Buddhist and Christian ordination, and funeral rituals. Outline I. Rituals are a central feature of human life, both individually and in community. Rituals are a prescribed set of actions that often employ powerful symbols to accomplish both religious and secular purposes. A. People in all cultures participate in rituals based on both the human lifecycle and the calendar. 1. In the United States, secular lifecycle rituals include graduation from high school, a swearing-in ceremony for a public official, initiation into a fraternity or sorority, a celebration on reaching the age of 21, and so on. 2. Common secular calendar rituals in the United States include such activities as reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to start the day at public school, ritual traditions around Thanksgiving, and birthday celebrations. B. James Livingston defines a religious ritual as “an agreed-upon, formalized pattern of ceremonial movements and actions carried out in a sacred context.” We will examine common features of both religious lifecycle and calendar rituals in this and the next lecture. C. Rituals share several common elements. The words, actions, and symbols are repetitive and obligatory, and they engage multiple senses in the process of accomplishing specific goals. II. French anthropologist Arnold van Gennep identified three stages commonly found in lifecycle rite-of-passage rituals: separation, transition, and reincorporation. A brief consideration of the structure of a high school graduation ceremony illustrates the three stages. III. Religious lifecycle rituals occur one time (theoretically) during the course of an individual’s lifecycle. The major religions we are considering incorporate rituals to mark four stages in the human lifecycle: birth, coming of age, marriage, and death. In the rituals associated with these events, we can identify the three stages of separation, transition, and reincorporation. A. Religious rituals associated with birth welcome or initiate the new life into the community of faith. 1. In Judaism, males are circumcised on the eighth day after birth, according to the covenant given in the Book of Genesis. 2. Many Christian denominations—Catholics, Orthodox, and some Protestants (such as Lutherans and Presbyterians)—practice infant baptism. Others practice “dedication of babies” in the belief that the ritual of baptism should take place only after one has made an adult profession of faith. B. Religious coming-of-age rituals are often associated with physical maturation around the time of puberty. 1. The Hindu sacred thread ceremony ( upanayana) initiates boys into their new role as students who will learn the teachings and practices required of their religion. 2. A Jewish boy or girl becomes a “son/daughter of the Commandment” through the prescribed ritual known as Bar or Bat Mitzvah . From this point forward, the young man or woman must follow Jewish Law, tradition, and ethics and participate fully in all aspects of Jewish community life. C. Marriage rituals mark a new stage of life—socially and legally—as individuals formally leave their families to form new homes. 1. Christian marriage ceremonies follow prescribed patterns (instruction, vows) and incorporate many religious symbols and dramatic elements, such as special music and visual effects to appeal to the senses. 2. The ordination of a Buddhist monk or a Christian monk, nun, or priest who takes a vow of celibacy is a parallel form of commitment within the respective religions. D. Rituals associated with death mark the end of an individual’s lifecycle and provide powerful moments to educate the religious community about the meaning of life and the changing human community of faith. 1. Muslim funeral practices prescribe burial of the deceased before sundown of the day after death and emphasize equality before God with burial in simple garments. The body is placed facing in the direction of Mecca. 2. Jewish rituals also require burial before sundown of the day following death, with the grave close to Jerusalem, if possible, in preparation for the coming of the messiah on the day of resurrection. Relatives and close friends stay with the body until the time of burial. 3. The traditional Hindu practice of cremation is based on the belief that the soul does not enter another body until the original body is returned to the basic elements. 4. Buddhist practices vary a great deal. Tibetan Buddhists, for example, engage in a lengthy, intricate ritual to help the deceased make the proper transition into a blissful state. 5. Christian funeral rites include many of the same components of separation, transition, and reincorporation visible in other religions. Suggested Readings: Catherine Bell, ed., Teaching Ritual. Jean Holm and John Bowker, Rites of Passage. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage. Questions to Consider: 1. Identify and describe five or more religiously connected lifecycle rituals with which you have personally been involved. In what ways have these been stale and perfunctory? In what ways have they been powerful, engaging, and memorable events for you or those you have observed obtaining a new status through the ritual event? 2. What might the rituals marking major stages of the human lifecycle in the different religions suggest about commonality across religious lines? ©

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret Bar Mitzvah, Bat Mitzvah and Confirmation http://www.jewfaq.org/barmitz.htm Jews become responsible for observing the commandments at the age of 13 for boys, 12 for girls• This age is marked by a celebration called bar (or bat) mitzvah• Some synagogues have an additional celebration called confirmation Bar Mitzvah and Bat Mitzvah"Bar Mitzvah" literally means "son of the commandment.” "Bar" is "son" in Aramaic, which used to be the vernacular of the Jewish people. "Mitzvah" is "commandment" in both Hebrew and Aramaic. "Bat" is daughter in Hebrew and Aramaic. (The Ashkenazic pronunciation is "bas"). Technically, the term refers to the child who is coming of age, and it is strictly correct to refer to someone as "becoming a bar (or bat) mitzvah." However, the term is more commonly used to refer to the coming of age ceremony itself, and you are more likely to hear that someone is "having a bar mitzvah" or "invited to a bar mitzvah."So what does it mean to become a bar mitzvah? Under Jewish Law, children are not obligated to observe the commandments, although they are encouraged to do so as much as possible to learn the obligations they will have as adults. At the age of 13 (12 for girls), children become obligated to observe the commandments. The bar mitzvah ceremony formally, publicly marks the assumption of that obligation, along with the corresponding right to take part in leading religious services, to count in a minyan (the minimum number of people needed to perform certain parts of religious services), to form binding contracts, to testify before religious courts and to marry.A Jewish boy automatically becomes a bar mitzvah upon reaching the age of 13 years, and a girl upon reaching the age of 12 years. No ceremony is needed to confer these rights and obligations. The popular bar mitzvah ceremony is not required, and does not fulfill any commandment. It is certainly not, as one episode of the Simpsons would have you believe, necessary to have a bar mitzvah in order to be considered a Jew! The bar or bat mitzvah is a relatively modern innovation, not mentioned in the Talmud, and the elaborate ceremonies and receptions that are commonplace today were unheard of as recently as a century ago In its earliest and most basic form, a bar mitzvah is the celebrant's first aliyah. During Shabbat services on a Saturday shortly after the child's 13th birthday, or even the Monday or Thursday weekday services immediately after the child's 13th birthday, the celebrant is called up to the Torah to recite a blessing over the weekly reading. Today, it is common practice for the bar mitzvah celebrant to do much more than just say the blessing. It is most common for the celebrant to learn the entire haftarah portion, including its traditional chant, and recite that. In some congregations, the celebrant reads the entire weekly torah portion, or leads part of the service, or leads the congregation in certain important prayers. The celebrant is also generally required to make a speech, which traditionally begins with the phrase "today I am a man." The father traditionally recites a blessing thanking G-d for removing the burden of being responsible for the son's sins (because now the child is old enough to be held responsible for his own actions).In modern times, the religious service is followed by a reception that is often as elaborate as a wedding reception.In Orthodox and Chasidic practice, women are not permitted to participate in religious services in these ways, so a bat mitzvah, if celebrated at all, is usually little more than a party. In other movements of Judaism, the girls do exactly the same thing as the boys.It is important to note that a bar mitzvah is not the goal of a Jewish education, nor is it a graduation ceremony marking the end of a person's Jewish education. We are obligated to study Torah throughout our lives. To emphasize this point, some rabbis require a bar mitzvah student to sign an agreement promising to continue Jewish education after the bar mitzvah.Sadly, an alarming number of Jewish parents today view the bar or bat mitzvah as the sole purpose of Jewish education, and treat it almost as a Jewish hazing ritual: I had to go through it, so you have to go through it, but don't worry, it will all be over soon and you'll never have to think about this stuff again.ConfirmationConfirmation is a somewhat less widespread coming of age ritual that occurs when a child is 16 or 18. Confirmation was originally developed by the Reform movement, which scorned the idea that a 13 year old child was an adult (but see explanation below). They replaced bar and bat mitzvah with a confirmation ceremony at the age of 16 or 18. However, due to the overwhelming popularity of the bar or bat mitzvah, the Reform movement has revived the practice. I don't know of any Reform synagogues that do not encourage the practice of bar and bat mitzvahs at age 13 today.In some Conservative synagogues, however, the confirmation concept has been adopted as a way to continue a child's Jewish education and involvement for a few more years.Is 13 an Adult?Many people mock the idea that a 12 or 13 year old child is an adult, claiming that it is an outdated notion based on the needs of an agricultural society. This criticism comes from a misunderstanding of the significance of becoming a bar mitzvah.Bar mitzvah is not about being a full adult in every sense of the word, ready to marry, go out on your own, earn a living and raise children. The Talmud makes this abundantly clear. In Pirkei Avot, it is said that while 13 is the proper age for fulfillment of the Commandments, 18 is the proper age for marriage and 20 is the proper age for earning a livelihood. Elsewhere in the Talmud, the proper age for marriage is said to be 16-24.Bar mitzvah is simply the age when a person is held responsible for his actions and minimally qualified to marry. If you compare this to secular law, you will find that it is not so very far from our modern notions of a child's maturity. In Anglo-American common law, a child of the age of 14 is old enough to assume many of the responsibilities of an adult, including minimal criminal liability. Under United States law, 14 is the minimum age of employment for most occupations (though working hours are limited so as not to interfere with school). In many states, a fourteen year old can marry with parental consent. Children of any age are permitted to testify in court, and children over the age of 14 are permitted to have significant input into custody decisions in cases of divorce. Certainly, a 13-year-old child is capable of knowing the difference between right and wrong and of being held responsible for his actions, and that is all it really means to become a bar mitzvah.Gifts One of the most common questions I get on this site is: do you give gifts at a bar or bat mitzvah, and if so, what kind of gifts?Yes, gifts are commonly given. They are ordinarily given at the reception, not at the service itself. Please keep in mind that a bar mitzvah is incorporated into an ordinary sabbath service, and many of the people present at the service may not be involved in the bar mitzvah.The nature of the gift varies significantly depending on the community. At one time, the most common gifts were a nice pen set or a college savings bond (usually in multiples of $18, a number that is considered to be favorable in Jewish tradition, see: Hebrew Alphabet: Numerical Values). In many communities today, however, the gifts are the same sort that you would give any child for his 13th birthday. It is best to avoid religious gifts if you don't know what you're doing, but Jewish-themed gifts are not a bad idea. For example, you might want to give a book that is a biography of a Jewish person that the celebrant might admire. I hesitate to get into specifics, for fear that some poor celebrant might find himself with several copies of the same thing!When in doubt, it never hurts to ask the parents or the synagogue's rabbi what is customary within the community.

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret Navjote Ceremony Anil Saigal 12/13/2002 One of the most important events in the life of a young Parsi child is the Navjote Ceremony. Rutty and Adi Guzdar recently celebrated this event for their grandchildren Simonne and Gabriel. Adi Guzdar is a charter member of TIE-Boston and very actively involved in its activities. Simmone is 11 years old and Gabriel is 7 years old and they live in Cincinnati. Their mother is Zerlina, daughter of Rutty and Adi. Zerlina is a Research Scientist in the Beauty Care Products Division of Proctor and Gamble. Phil, their father, works in Cincinnati as and Independent Financial Consultant.It was a proud day in the lives of Adi and Rutty as the performed the Navjote Ceremony The word Navjote is made up of two concepts: Nav, meaning new, and Zote, meaning one who offers prayers. In preparation for the ceremony, the children are told the story of Zarathustra. Through this life-story, the children are taught the fundamentals of the religion -a very rare and free religion, where nothing is imposed on one except the advice of good thoughts, good words, and good deeds, along with the great traditions of charity towards all, kindness, consideration to the less fortunate, and the care of and respect towards the elements and the environment. The child is taught that there is only one God and that He is all knowing, all wise and everywhere. God is in all the good souls of humankind. The concept of freedom of choice - to choose between right and wrong - is introduced and the child is taught that God wants us to choose the good path of our own free will. Basic prayers, which are said during the Navjote ceremony, have been learned by the children. The ceremony consists of a sacred shirt called the Sudrah and a sacred thread called Kusti. The Sudrah is made out of white cotton cloth. White is the symbol of purity and cotton is used to show that in God's eyes rich and poor are equal. It has a V-shaped neck in front. The tip of the V is the most important part of the Sudrah, called the Gireban. This is the pocket of good thoughts. It has a slit in the center for the good thoughts to enter and is a one-inch square piece of the same cloth. The Kusti is made of wool from lamb, which has pure white fleece.Just before the ceremony starts, the children are given the Nahn, or the purification bath. The children enter the room with their family. The family will carry a Ses containing the new clothes to be worn after the ceremony. The children are led to the place where the ceremony is to be performed. The stage is covered with a white sheet and a fire is lit. There is also a tray filled with rose petals, rice, and pomegranate seeds, which will be sprinkled on the children.At the end of the ceremony Simonne and Gabriel's parents and grandparents wish them well. The children leave to put on their new clothes and then return to social segment of the ceremony.A final thought from all present - we can all live richer lives if we have: Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds. Perhaps this is the very essence of all religions.

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret Pollywog tradtions

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret The first woman, White Painted Woman (also known as Esdzanadehe, and Changing Woman) survives the great Flood in an abalone shell, then wanders the land as the waters recede. Atop a mountain, she is impregnated by the sun, and gives birth of a son, Killer of Enemies. Soon afterwards, she is impregnated by the Rain, and gives birth to Son of Water. However, the world the People live in is not safe until White Painted Woman's sons kill the Owl Man Giant who has been terrorizing the tribe. When they return from their victory, bringing the meat they have hunted, White Painted Woman expresses a cry of triumph and delight, which later will be echoed by the godmother at the Sunrise Ceremony. She then is guided by spirits to establish a puberty rite to be given for all daughter born to her people, and to instruct the women of the tribe in the ritual, and the rites of womanhood.When she becomes old, White Painted Woman walks east toward the sun until she meets her younger self, merges with it, and becomes young again. Thus repeatedly, she is born again and again, from generation to generation. What purpose does it serve for the girls who experience it? The Sunrise Ceremony serves many purposes - personally, spiritually and communally - and is often one of the most memorable and significant experiences of Apache females today, just as it was for Apache women in the past.First, by re-enacting the Creation myth, and personifying White Painted Woman, the girl connects deeply to her spiritual heritage, which she experiences, often for the first time, as the core of her self. In her connection to Changing Woman/ White Painted Woman, she gains command over her weaknesses and the dark forces of her nature, and knows her own spiritual power, sacredness and her goodness. She also may discover her own ability to heal. Second, she learns about what it means to become a woman, first through attunement to the physical manifestations of womanhood such as as menstruation (and learning about sexuality), as well as the development of physical strength and endurance. The rigorous physical training she must go through in order to survive four days of dancing and running is considerable, and surviving and triumphing during the "sacred ordeal" strengthens her both physically and emotionally. Most Apache women who have experienced the Sunrise Ceremony say afterwards that it significantly increased their self-esteem and confidence. When it ended, they no longer felt themselves to be a child; they truly experienced themselves as "becoming woman."Third, the Apache girl entering womanhood experiences the interpersonal and communal manifestations of womanhood in her culture - the necessity to work hard, to meet the needs and demands of others, to exercise her power for others' benefit, and to present herself to the world, even when suffering or exhausted, with dignity and a pleasant disposition. Her temperament during the ceremony is believed to be the primary indicator of her temperament throughout her future life. Not only does she give to the community - food, gifts, healings, blessings, but she also joyfully receives from the community blessings, acceptance and love. Throughout the ceremony, she receives prayers and heartfelt wishes for prosperity, wellbeing, fruitfulness, a long life, and a healthy old age. Finally, the Sunrise ceremony serves the community as well as the girls entering womanhood. It brings extended families and tribes together, strengthening clan obligations, reciprocity and emotional bonds, and deepening the Apache's connection to his or her own spiritual heritage.

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret

- Humanities 1: Dr. Dylan Eret