Drainage in New Orleans

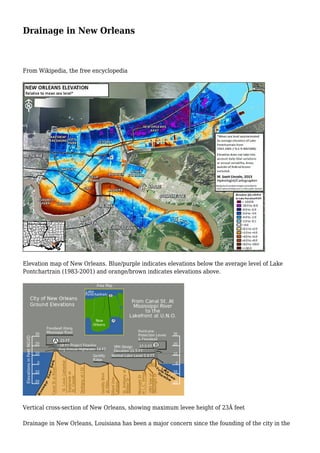

- 1. Drainage in New Orleans From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Elevation map of New Orleans. Blue/purple indicates elevations below the average level of Lake Pontchartrain (1983-2001) and orange/brown indicates elevations above. Vertical cross-section of New Orleans, showing maximum levee height of 23Â feet Drainage in New Orleans, Louisiana has been a major concern since the founding of the city in the

- 2. early 18th century, remaining an important factor in the history of New Orleans today. The central portion of metropolitan New Orleans (New Orleans/Metairie/Kenner) is fairly unique in that it is almost completely surrounded by water: Lake Pontchartrain to the north, Lake Borgne to the east, wetlands to the east and west, and the Mississippi River to the south. Much of the land area between these bodies of water is at or below sea level, and no longer has a natural outlet for flowing surface water. As such, virtually all rainfall occurring within this area must be removed through either evapotranspiration or pumping. Thus, flood threats to metropolitan New Orleans include the Mississippi River, Lake Pontchartrain, and natural rainfall. Artificial levees have been built to keep out rising river and lake waters but have had the negative effect of keeping rainfall in. Contents 1 History 2 Hurricane Katrina 2.1 After Katrina 3 See also 4 References 5 External links History New Orleans was originally built on natural levees along the Mississippi River that were a result of soil deposits left from the river's annual floods. The site chosen for New Orleans had many advantages. Because it sits where distance between the river and Lake Pontchartrain is shortest, Louisiana Indians had long used the area as a depot and market for goods carried between the two waterways. The narrow strip of land also aided rapid troop movements, and the river's crescent shape slowed ships approaching from downriver and exposed them to gunfire,[1] however flooding was always a hazard. The first artificial levees and canals were built in early colonial times. They were erected to protect New Orleans against routine flooding from the Mississippi River. The "back of town" away from the river originally drained down into the swamps running toward Lake Pontchartrain. Flooding from the lake side was rare and less severe as most of the old town had been built on high ground along the riverfront. As the city grew, demand for more land encouraged expansion into lower areas more prone to periodic flooding. For most of the 19th century most residential buildings were raised up at least a foot above street level (often several feet), since periodic flooding of the streets was a certainty at the time. In the 1830s state engineer George T. Dunbar proposed an ambitious system of underground drainage canals beneath the streets. The goal was to drain water by gravity into the low lying swamps, supplementing this with canals and mechanical pumps. The first of the city's steam engine powered drainage pumps, adapted from a ship's paddle wheel and used to push water along the Orleans Canal out to Bayou St. John, was constructed in this decade. However, only a few of Dunbar's plans were actually implemented as the panic of 1837 largely ended major systematic

- 3. improvements for a generation. In 1859 surveyor Louis H. Pilié improved the drainage canals, bricking in some portions. Four large steam "draining machines" were built to push water through the canals into the lake. In 1871, some 36 miles (58 km) of canals were built in the city for both improved drainage and small vessel shipping within town. However, despite earlier efforts, at the end of the 19th century it was still common for water to cover streets from curb to curb after rainstorms, sometimes for days. In 1893, the city government formed the Drainage Advisory Board to come up with better solutions to the city's drainage problems. Extensive topographical maps were made and some of the nation's top engineers were consulted. In 1899, a bond was floated, and a 2 mill per dollar property tax approved, which funded and founded the Sewerage & Water Board of New Orleans. The Sewerage & Water Board had the responsibility of draining the city along with constructing a modern sewage and tap water system for the city, which, at the time, still relied heavily on cisterns and outhouses. (A different entity, the Orleans Levee Board, is in charge of supervision of the city's levee and floodwall system.) The Sewerage & Water Board found A. Baldwin Wood, a young engineer who not only supervised the plans for improved drainage and pumping, but also invented a number of improvements in pumps and plumbing in the process. These improvements were not only used in New Orleans, but adopted all over the world. The central power plant for the pumping stations of the New Orleans drainage system, 1904 As the 20th century progressed, much of the land that had previously been swampland or considered fit for no other use than cow pasture (due to periodic flooding), was drained. The city then expanded back from the natural higher ground close to the river and the natural bayou formed ridges. On 15 April 1927 in what became known as the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the city was deluged by a downpour of some 15 inches (380 mm) of rain within 19 hours. At the time, almost all of the city's pumps relied completely on the municipal electricity system, which went out early in the storm, thus knocking the pumps off line, which led to extensive flooding in the city. After this, back up diesel generators with sufficient fuel to run the pumps for at least a day if electricity failed were added to the pumping stations. The "Good Friday Flood", as it was known locally, happened when the Mississippi River levels were dangerously high along the levees at the city, but was not directly connected to the more wide-ranging flood.

- 4. 1927 also saw the start of a project to build a more extensive system of levees on the shoreline of Lake Pontchartrain. After 1945, all land up to the lake had been developed. The city's system was effective when the 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane directly hit the city. Wood's drainage pumps kept the city proper mostly dry, while the neighboring suburbs on the East Bank of Jefferson Parish (which at the time did not have a comparable system operational), flooded under up to 6 feet (1.8Â m) of water. Most of the city weathered Hurricane Betsy in 1965 without severe flooding, with the major exception of the Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood. The Lower Ninth Ward is separated from the rest of the city by the Industrial Canal and Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. It was flooded not by rainfall, but by a breach in the Industrial Canal levee, resulting in catastrophic flooding and loss of life in the neighborhood. By the 1980s, the city boasted a system of 20 pumping stations with 89 pumps, with a combined capacity of 15,642,000 US gallons (59,210,000Â L) per minute, equal to the flow of the Ohio River. In May 1995, torrential rains (up to 20 inches (510Â mm) in 12 hours in some places) overwhelmed pumping capacity, flooding substantial portions of the city. Slab houses in some low areas were flooded, and great numbers of automobiles on the city's flooded streets were declared insurance write-offs. This prompted projects increasing drainage capacity in the worst hit areas. By early 2005, the city had 148 drainage pumps. Hurricane Katrina Main article: Hurricane Katrina The greatest catastrophe in the city's drainage history occurred at the end of August 2005 when it was hit by Hurricane Katrina, after which eighty percent of the city flooded. Katrina brought tropical storm conditions to the city starting the night of 28 August, with hurricane conditions beginning the following day and lasting through the afternoon. The hurricane itself did not flood the city. Rather, a series of failures in mis-designed levees and floodwalls allowed water from the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Pontchartrain to flow into the city. The Industrial Canal was overwhelmed when storm surge, funneled in by the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, overflowed and breached levees and floodwalls in several locations, flooding not only the Lower Ninth Ward, but also Eastern New Orleans and portions of the Upper Ninth Ward west of the Canal. Meanwhile, waters from storm-swollen Lake Pontchartrain poured into the city, first from a breach in the 17th Street Canal, and then from a pair of breaches in both sides of the London Avenue Canal. These canals were among those used to channel water pumped from city streets into the lake. The storm caused the flow to reverse, and as water levels rose the entire drainage system failed. Examinations afterwards showed that water levels in these locations never topped the floodwalls, but instead the levees failed with a water level supposedly within their safe tolerance. In much of town west of the Industrial Canal, residents who did not evacuate before the storm reported that after the storm they were relieved to see their streets dry and the precipitation from the storm successfully pumped out. However, disaster was already spreading from the series of

- 5. levee breaches. In areas of town far from the breaches, flood water came not in through the streets, but up from the storm drains beneath the street, in some places changing streets from dry to under 3 feet (0.91Â m) of water within half an hour. Flood lines show levels of high water on this Mid City New Orleans house By the evening of August 30, some 80% of the city was under water. (This figure includes areas of widely differing flood levels, ranging from areas where streets were covered with water which never rose into homes to areas where homes were entirely submerged over the rooftops.) Most of the city's pumping stations were submerged. The few above the water line had no power and the emergency diesel fuel had run out. These few were often tiny islands in the flood, inaccessible even if intact enough to hypothetically be turned back on. For most of the city to the west of the Industrial Canal, the flood levels were much the same as those reached in mid-19th century storms when, like Katrina, major hurricanes created a "lake flood" by pushing Lake Pontchartrain up into the South Shore. At the time of these earlier storms the lower lying areas of the city had little development, so effects on life and property were much less severe. West of the Industrial Canal, the parts of the city unflooded or minimally flooded largely corresponded with areas of the city developed on naturally higher ground before 1900. On August 31, flood levels started to subside. The water level in the city had reached that of Lake Pontchartrain, and as the lake started to drain back into the Gulf, some water in the city started to flow into the lake via the same levee breeches they had entered through. In 19th century lake floods, the water soon flowed back into the lake as there were no levees on that side. In 2005, while the levees proved inadequate to keep the lake out of the city, even in breached form they were sufficient to keep much of the flooding from flowing back out. As breaches were gradually filled, some city pumps were reactivated, supplemented by additional pumps brought in by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Some of the city's pumps which survived could not be reactivated because of the failures of the canals that they pumped flood waters into. The combined task of closing breaches and pumping the flood waters out took weeks and was compounded by a setback in late September due to further flooding from Hurricane Rita. After Katrina Main article: 2005 levee failures in Greater New Orleans

- 6. See also: Civil engineering and infrastructure repair in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina By the start of October 2005, only a few small areas of flood waters remained within the city, but the disastrous flooding in the aftermath of Katrina left the majority of the city's houses and businesses so damaged as to be unusable until major renovations or repairs could be made. An article in the New Orleans Times-Picayune on 30 November 2005 reported that studies showed the 17th Street Canal levee was "destined to fail" as a result of fundamental design mistakes by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.[2] Additional investigations have found more problems with the design and construction of the London Avenue Canal, Industrial Canal, MRGO, and other levees and flood walls. While the majority of the city's drainage pumps were able to be reactivated after the storm, some of the usually reliable pumps failed in 2006 due to corrosion. This was caused by wiring being submerged in the brackish water from Katrina. As a stop-gap measure, the Corps of Engineers installed flood gates at the mouths of the drainage canals at Lake Pontchartrain, to be closed if the lake water level rises. While this prevents lake waters from flowing into the vulnerable canals, it also severely limits the ability of the city to pump out rain water while the gates are closed. In March 2006, it was revealed that temporary pumps installed by the USACE were defective.[3][4] Until all problems are rectified, concerns remain that parts of the city could experience significant flooding in a storm much smaller than Katrina. The system did survive during Hurricane Gustav in 2008. The storm weakened and brought less wind and rain than forecast. "The Lakefront pumps operated smoothly".[5] Metarie Pumping Station, also known as Pumping Station 6, building, constructed in 1899, near Metarie Road and the head of the 17th Street Canal. Now housing 15 Wood Screw Pumps, it can move over 6 billion US gallons (23,000,000 m3) of water a day. See also 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane Bonnet Carré Crevasse Bonnet Carré Spillway Effect of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans

- 7. Floods in the United States: 1901-2000 Floods in the United States: 2001-present Grand Isle Hurricane of 1909 Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 Hurricane Betsy Hurricane Katrina Hurricane Rita Levee failures in Greater New Orleans, 2005 May 8th 1995 Louisiana Flood New Orleans Hurricane of 1915 Orleans Levee Board Sauvé's Crevasse Southeast Louisiana Urban Flood Control Project References Notes ^ "The Cabildo - Colonial Louisiana". Louisiana State Museum. Retrieved 11 August 2010. ^ "?". ^ "?". Retrieved 11 August 2010. ^ "?". Retrieved 11 August 2010. ^ "?". Retrieved 11 August 2010. Bibliography "Charting Louisiana" Edited by Alfred E. Lemmon, John T. Magill, and Jason R. Wiese; John R. Hebert, consulting editor. Historic New Orleans Collection, 2003 "Geographies of New Orleans" by Richard Campanella, Center for Louisiana Studies, 2006 "History of New Orleans" by John Kendall. Lewis Publishing Company, 1922 "New Orleans The Making of an Urban Landscape" by Peirce F. Lewis. Second Edition, Center for American Places, 2003

- 8. "Time and Place in New Orleans" by Richard Campanella. Pelican Publishing Company, 2002 "Transforming New Orleans and Its Environs" edited by Craig E. Colten. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000. "An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans From Nature" by Craig E. Colten, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 2005 "Topical and Drainage Map of New Orleans and Surroundings From Recent Surveys and Investigations, by T. S. Hardee, Civil Engineer. Thomas Sydenham Hardee, 1878 External links Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drainage in New Orleans. New Orleans: The Story of Three Great Public Utilities, 1914 History of New Orleans Drainage, 1718-1893 PDF The Wood Screw Pump: A Study of the Drainage Development of New Orleans New Orleans: A Wonderful Drainage System. Colliers Weekly, 1901 New Orleans Hurricane Risk Public Health and Hurricanes: New Orleans Pilot Project "Fix The Pumps" blog detailing post-Katrina repairs Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Drainage_in_New_Orleans&oldid=610397422"