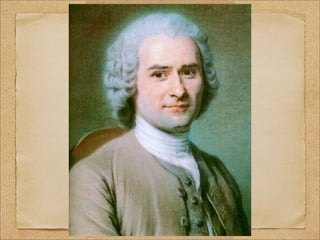

Rousseau's Early Life & Influences

- 1. Rousseau Justice & Power, session viii

- 2. Rousseau Justice & Power, session viii

- 3. Topics in This Session i.Early Life ii.Writing iii.Du contrat social, 1762 iv.Criticism

- 4. Early Life

- 5. Early Life Rousseau meets Mme de Warens

- 6. I. Early Life A. parents 1. déclassé B. education 1. reading 2. apprenticeship C. leaving Geneva 1. curfew, 1728 2. conversion D. no vocation 1. relations with women a. Mme de Warens b. Thérèse Levasseur 2. ministry, tutoring, diplomacy, clerking 3. music

- 8. A plaque commemorating the bicentenary of Rousseau's birth. Issued by the city of Geneva on 28 June 1912. The legend at the bottom says "Jean- Jacques, aime ton pays" ("love your country"), and shows Rousseau's father gesturing towards the window. The scene is drawn from a footnote to the Letter to d'Alembert where Rousseau recalls witnessing the popular celebrations following the exercises of the St Gervais regiment. Wikipedia

- 9. ...in his Letter to M. D’ Alembert on the Theater written when he was forty-five, there is an eloquent passage which reads: I remember being struck in my childhood by a rather simple scene...the St. Gervais militia had completed their exercises and, as was the custom, each of the companies ate together; and after supper most of them met in the square of St. Gervais, where the officers and soldiers all danced together around the fountain. My father, embracing me, was thrilled in a way that I can still feel and share. ‘Jean-Jacques’, he said to me, ‘love your country. Look at these good Genevans, they are all friends; they are all brothers; joy and harmony reigns among them. You are a Genevan. One day you will see other nations, but even if you travel as far as your father has, you will never find any people to match your own. Maurice Cranston, trans., Introduction, Rousseau; A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, 1984. pp. 18-1 9

- 10. Rousseau’s parents Isaac Rousseau Suzanne Bernard Rousseau 1672-1747 1673-1712 3rd generation Genevan from a wealthier family with watchmaker connections to the Genevan academic elite married “above his station” her father was a Calvinist himself, well educated, saw to preacher, her uncle left her a his son’s education beautiful home and impressive library 1722-exiled after a quarrel, left his son to the care of his she died 9 days after giving brother-in-law Gabriel birth to Jean-Jacques Bernard, went to Turkey

- 11. The house where Rousseau was born at number 40, place du Bourg-de-Four, Geneva.

- 12. I.B.1-reading Rousseau had no recollection of learning to read, but he remembered how when he was 5 or 6 his father encouraged his love of reading: Every night, after supper, we read some part of a small collection of romances [i.e., adventure stories], which had been my mother's. My father's design was only to improve me in reading, and he thought these entertaining works were calculated to give me a fondness for it; but we soon found ourselves so interested in the adventures they contained, that we alternately read whole nights together and could not bear to give over until at the conclusion of a volume. Sometimes, in the morning, on hearing the swallows at our window, my father, quite ashamed of this weakness, would cry, "Come, come, let us go to bed; I am more a child than thou art." Confessions, Book 1 Not long afterward, Rousseau abandoned his taste for escapist stories in favor of the antiquity of Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, which he would read to his father while he made watches. Wikipedia, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- 13. [After his father’s exile] Jean-Jacques was left with his maternal uncle, who packed him, along with his own son, Abraham Bernard, away to board for two years [1722-24] with a Calvinist minister in a hamlet outside Geneva. Here the boys picked up the elements of mathematics and drawing. Rousseau, who was always deeply moved by religious services, for a time even dreamed of becoming a Protestant minister. Ibid.

- 14. I.B.2-apprenticeship & C.1.curfew Virtually all our information about Rousseau's youth has come from his posthumously published Confessions, in which the chronology is somewhat confused, though recent scholars have combed the archives for confirming evidence to fill in the blanks. At age 13, Rousseau was apprenticed first to a notary and then to an engraver who beat him. At 15, he ran away from Geneva (on 14 March 1728) after returning to the city and finding the city gates locked due to the curfew. Ibid.

- 15. I.C.Leaving Geneva 2.conversion In adjoining Savoy he took shelter with a Roman Catholic priest, who introduced him to Françoise-Louise de Warens, age 29. She was a noblewoman of Protestant background who was separated from her husband. As professional lay proselytizer, she was paid by the King of Piedmont to help bring Protestants to Catholicism. They sent the boy to Turin, the capital of Savoy (which included Piedmont, in what is now Italy), to complete his conversion. This resulted in his having to give up his Genevan citizenship, although he would later revert to Calvinism in order to regain it. In converting to Catholicism, both De Warens and Rousseau were likely reacting to Calvinism's insistence on the total depravity of man. Leo Damrosch writes, "an eighteenth-century Genevan liturgy still required believers to declare ‘that we are miserable sinners, born in corruption, inclined to evil, incapable by ourselves of doing good'." De Warens, a deist by inclination, was attracted to Catholicism's doctrine of forgiveness of sins. Ibid.

- 16. Les Charmettes the house where Jean-Jacques Rousseau lived with Mme de Warens It is now a museum dedicated to Rousseau

- 17. Les Charmettes the house where Jean-Jacques Rousseau lived with Mme de Warens It is now a museum dedicated to Rousseau

- 18. 1.D.- no vocation 1.relations with women a.Mme de Warens 1699-born a Swiss Protestant, at age 26, she emigrated to Annecy, Savoy 1726-that year, she converted to Roman Catholicism & annulled her marriage. She then received a fee for converting Genevan Protestants 1728-Palm Sunday-age 28, met Rousseau (15) and became his benefactress and, later, his mistress. He called her maman. 1733-She(33) took him (20) as a lover. She was also intimate with her servant. “This ménage à trois left him sexually confused”-Wiki Françoise-Louise de Warens “She gave [him] the education he lacked and fulfilled 1699-1762 his hungry spirit, his need for love. Rousseau never forgot her.” --French Wiki

- 19. 1.D.1.b. - Thérèse Le Vasseur “At first I sought to give myself amusement, but I saw I had gone further and had given myself a companion.”-- Confessions 1745-later, Rousseau (33) began an affair with Marie-Thérèse (24) she was a seamstress, sole support of her family in the Confessions he would refer to her as his “wife, mistress, servant, daughter”-German Wiki his friends, fellow philosophes, were at a loss to explain their partnership. She seemed “beneath his station,” certainly, she was less than beautiful they never married, had four children, all of whom were given to a foundling hospital, i.e., orphaned although he would take up with other women, he Thérèse Le Vasseur would return to this other great love at life’s end 1721-1801

- 20. I.D-no vocation.2-ministry, tutoring 1722-24--he considered becoming a Calvinist minister 1725-28--two different failed apprenticeships 1729--sent to Turin to become grounded in his new Catholic faith, he left the minor seminary. He had no vocation for ministry in the Church of Rome either 1730-returning to Mme de Warens, he took music and other lessons. He began copying music to earn money and tutoring a few of the local youth 1737-he came into a small inheritance from his mother and used a portion of it to repay his benefactress 1739-he moved to Lyons and became a tutor there 1742-not satisfied with this lifestyle, he went to Paris to present to the Académie des Sciences a new system of musical notation which he believed would make his fortune. Without success.

- 21. 1.D.2.diplomacy 1743-44-as secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, he travelled to Venice the ambassador regarded him as a sort of servant, but Rousseau acted as if he were much more like a member of the diplomatic staff needless to say, this was a disaster waiting to happen there were arguments over pay, which was delayed because the ambassador himself received his stipend from Paris as much as a year late after eleven months of bickering Rousseau was Palazzo in Venice that served as dismissed. Clearly he had no vocation for the French Embassy during Rousseau's period as Secretary diplomacy to the Ambassador

- 22. 1.D.2.diplomacy [a different take] In 1743 Rousseau was thirty-one years old and working as private secretary to the Comte de Montaigu, French Ambassador to the Venetian Republic. This place gave Rousseau his first intimate acquaintance with politics and government. The ambassador was a retired general with no qualifications or aptitude for diplomacy. Rousseau, who was quick and capable, and could speak Italian, performed the duties of Embassy Secretary. Unfortunately, he had no official status; he was not a diplomatist; he was the ambassador’s personal employee; he was, as the ambassador tactlessly reminded him from time to time, a domestic servant. Rousseau felt cheated and humiliated. To do the work of a diplomatist and be treated as a lackey was unbearable.* Within a year he was gone, dismissed, and not even given his promised wages. *Indeed Voltaire put about the false story that Rousseau had been the ambassador’s valet, not his secretary. For evidence of Rousseau’s duties at the Embassy, see R.A. Leigh, ed., Correspondance complète de Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Geneva, 1965, as quoted in Maurice Cranston, trans., Rousseau; The Social Contract, 1968. p. 9

- 23. 1.D.3-music scene from his opera Le Devin du Village

- 24. 1.D.3-music Rousseau continued his interest in music. He wrote both the words and music of his opera Le Devin du Village (The Village Soothsayer), which was performed for King Louis XV in 1752. The king was so pleased by the work that he offered Rousseau a lifelong pension. To the exasperation of his friends, Rousseau turned down the great honor, bringing him notoriety as "the man who had refused a king's pension." The opera remained popular and was performed at the wedding of the Dauphin and Marie Antoinette. He also turned down several other advantageous offers, sometimes with a brusqueness bordering on truculence that gave offense and caused him problems. Ibid.

- 25. Writing

- 27. II. Writing A. Dijon competition, 1749 1. road to Vincennes jail 2. Discours sur les sciences et les arts, 1750 3. notoriety B. dropping out C. Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, 1755 1. natural 2. moral (political & social) 3. “the last term of inequality” D. Discourse on Political Economy, 1755 1. political equality and respect for Volonte General 2. universal public education 3. egalitarian fiscal policy E. Montmorency, 1756-62 1. romance and Nouvelle Heloise, 1761 2. Emile :Ou de l’education, 1762 a. “follow nature” b. progressive dogmas

- 28. II.A. Dijon Competition, 1749-1.road to Vincennes jail Every reader of the Confessions must remember the story Rousseau tells of his walk to Vincennes to visit Diderot when he was imprisoned there, and his discovering on the way an advertisement for a prize essay at Dijon on the subject of how the revival of the arts and sciences had improved men’s morals, and his realization in a blinding flash, that such progress had in fact corrupted morals. Hardly able to breathe, let alone walk, he tells us, he sat down under a tree and wept. Cranston, Inequality, p. 24

- 29. II.A.2 he “wrote Discourse in response to an advertisement that appeared in a 1749 issue of Mercure de France, which offered a prize for an essay responding to the question: "Has the restoration of the sciences and the arts contributed to refining moral character?" “nature made man happy and good, but… society depraves him and makes him miserable ...vice and error, foreign to his constitution, enter it from outside and insensibly change him." Rousseau "authored a scathing attack on scientific progress...an attack whose principles he never disavowed."--JJS Black in Wiki Rousseau anticipated that his response would cause "a universal outcry against me", but held that "a few sensible men" would appreciate his position

- 30. II. A. 3. notoriety Rousseau's argument was controversial, and drew a great number of responses. One from critic Jules Lemaître calling the instant deification of Rousseau as 'one of the strongest proofs of human stupidity.' Rousseau himself answered five of his critics in the two years or so after he won the prize. Among these five answers were replies to Stanisław Leszczyński, King of Poland, M. l'Abbe Raynal, and the "Last Reply" to M. Charles Bordes. These responses provide clarification for Rousseau's argument in the Discourse, and begin to develop a theme he further advances in the Discourse on Inequality – that misuse of the arts and sciences is one case of a larger theme, that man, by nature good, is corrupted by civilization. Inequality, luxury, and the political life are identified as especially harmful. Wikipedia, “Discourse on the Arts and Sciences”

- 31. II. B. dropping out (underlying causes) What [had] made the Comte de Montaigue’s attitude [in Venice in 1743]the more unbearable to Rousseau was not only the injustice, but also the underlying reality: Jean-Jacques was a servant, and he had never been anything much better. He had the soul and the mind, as the whole world was soon to recognize, of an exceptional and superior being, but his rank and condition were humble. __________ Cranston, Social Contract. p. 9 He also had a urinary disease which afflicted him increasingly during this time and required him to wear a catheter.* This could not help but increase his discomfort in social settings--jbp *op. cit., p. 23

- 32. II. B. dropping out (rejection of the social conventions) Rousseau entered midlife at this time and despite the widespread recognition which his prize gave him, he began to shun society. This is when he refuses to dress up, go to Versailles, and receive the annuity which Louis xv offered as a reward for his opera. He enjoyed the fame among the upper classes and the appreciation of many of them. But he resented the fact that his birth and condition kept him as an outsider. “...he was painfully ill at ease in the salons, in social gatherings that were governed by intricate rules of behavior….he began to live what he spoke of as a ‘life of solitude’.”* Still, his friend, Diderot commissioned him to write 344 articles for his Encyclopédie at this time. But first, he would pour out his frustration over social inequality.--jbp _______________________ * Cranston, Inequality. p. 18

- 33. II. B. dropping out (the Encyclopedists) The Encyclopaedists were immensely influenced by Bacon [Sir Francis Bacon, 1561-1626]--they spoke a lot about Locke, but Bacon was really their hero; and although Montesquieu continued to uphold Locke’s kind of politics, the other Encyclopaedists were drawn ever closer to Bacon with his radical scheme to wipe away religion and traditional philosophy and replace it with the role of science and technology aimed at improving the life of man on earth. Science was to be the salvation of mankind. Bacon’s personal project was to make James I a king who would use his absolute powers to govern scientifically as Bacon advised him to govern; and this was the package which Voltaire, Holbach and La Rivière tried to sell such monarchs as Frederick II of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia. [ la despotisme éclairé (Enlightened Despotism)]* _______________________ *Ibid. p. 18

- 34. II. C * * The matter ought to be considered as it is according to its nature, not as it is in its present depravity. ARISTOT.. Politic. I, 2

- 35. II. C Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes), also commonly known as the "Second Discourse". The text was written in 1754 in response to another prize competition of the Academy of Dijon answering the prompt: What is the origin of inequality among men, and is it authorized by natural law? Though he was not recognized by the prize committee for this piece (as he had been for the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences) he nevertheless published the text in 1755. Wikipedia

- 36. II.C.1-3 1. there were two sorts of inequality. The first, “natural," such as height, strength &c. This type of inequality was relatively unimportant 2.the second type, “moral,” that is, political and social, is endemic to society and causes differences in power and wealth. Society is a trick perpetrated by the powerful on the weak in order to maintain their power and wealth

- 37. II. C. “The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said "This is mine," and found people naïve enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, p. 109

- 38. II. C. a cynicism about “mankind in general” as profound as Machiavelli’s “Finally, a devouring ambition, the burning passion to enlarge one’s fortune, not so much from real need as to put oneself ahead of others, inspires in all men a dark propensity to injure one another, a secret jealousy which is all the more dangerous in that it often assumes the mask of benevolence in order to do its deeds in greater safety; in a word, there is competition and rivalry on the one hand, conflicts of interest on the other, and always the hidden desire to gain an advantage at the expense of other people. All these evils are the main effects of property and the inseparable consequences of nascent inequality.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, p. 119

- 39. II.C.1-3 1. there were two sorts of inequality. The first, natural," such as height, strength &c. was relatively unimportant 2.the second, “moral,” that is, political and social, is endemic to society and causes differences in power and wealth. Society is a trick perpetrated by the powerful on the weak in order to maintain their power and wealth 3.he concludes that “the last term [in a series of historical developments] of inequality is despotism”

- 40. II. C. 3 “...despotism….This is the last stage of inequality, and the extreme term which closes the circle and meets the point from which we started. It is here that all individuals become equal again because they are nothing, here where subjects have no longer any law but the will of the master….Here everything is restored to the sole law of the strongest….The insurrection which ends with the strangling or dethronement of a sultan is just as lawful an act as those by which he disposed the day before of the lives and property of his subjects. Force alone maintained him; force alone overthrows him…..” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Inequality, pp. 134-35

- 41. II. D. Discourse on Political Economy, 1755 Rousseau begins this article for Diderot’s Encyclopedia with a description of the state as a mechanical man, just as Hobbes did in his introduction to Leviathan. jbp

- 42. II. D. Discourse on Political Economy, 1755 Rousseau begins this article for Diderot’s Encyclopedia with a description of the state as a mechanical man, just as Hobbes did in his introduction to Leviathan. jbp

- 43. II. D. a.-political equality and respect for the Volonte Géneral 1. As might be expected from his critical writing on inequality, this article emphasized the need for political equality. In addition to advocating universal manhood suffrage, he makes first mention of his concept of the General Will. jbp

- 44. II. D. 1 “The body politic, therefore, is also a moral being possessed of a will; and this general will, which tends always to the preservation and welfare of the whole and of every part, and is the source of the laws, constitutes for all the members of the State, in their relations to one another and to it, the rule of what is just or unjust...” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Political Economy

- 45. II. D. Discourse on Political Economy, 1755 1. As might be expected from his critical writing on inequality, this article for the Encyclopédie emphasized the need for political equality. In addition to advocating universal manhood suffrage, he makes first mention of his concept of the General Will. 2. He is also an early advocate of free universal public education. jbp

- 46. II. D. 2 T form citizens is not the work of a day; and in order to have men it is o necessary to educate them when they are children….It is too late to change our natural inclinations, when they have taken their course, and egoism is confirmed by habit: it is too late to lead us out of ourselves when once the human Ego, concentrated in our hearts, has acquired that contemptible activity which absorbs all virtue and constitutes the life and being of little minds….Government ought the less indiscriminately to abandon to the intelligence and prejudices of fathers the education of their children, as that education is of still greater importance to the State than to the fathers….Public education, therefore, under regulations prescribed by the government...is one of the fundamental rules of popular or legitimate government. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Political Economy

- 47. II. D. Discourse on Political Economy, 1755 1. As might be expected from his critical writing on inequality, this article for the Encyclopédie emphasized the need for political equality. In addition to advocating universal manhood suffrage, he makes first mention of his concept of the General Will. 2. He is also an early advocate of free universal public education. 3. Finally, he argues that the tax structure needed to advance a more equal distribution of wealth instead of the present regressive system. jbp

- 48. II. D. 3 III. It is not enough to have citizens and to protect them, it is also necessary to consider their subsistence. Provision for the public wants is an obvious inference from the general will, and the third essential duty of government. This duty is not...to fill the granaries of individuals and thereby to grant them a dispensation from labour, but to keep plenty so within their reach that labour is always necessary and never useless for its acquisition. It extends also to everything regarding...the expenses of public administration. It should be remembered that the foundation of the social compact is property; and its first condition, that every one should be maintained in the peaceful possession of what belongs to him. It is true that, by the same treaty, every one binds himself...to be assessed toward the public wants:... it is plain that such assessment...must be voluntary; it must depend, not indeed on a particular will, as if it were necessary to have the consent of each individual,...but on a general will, decided by vote of a majority, and on the basis of a proportional rating which leaves nothing arbitrary in the imposition of the tax. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on Political Economy

- 49. a cosy retreat--L’Hermitage in the vale of Montmorency, now a Parisian suburb 15 km

- 50. a cosy retreat--L’Hermitage in the vale of Montmorency, now a Parisian suburb his hostess Mme d’Épinay

- 51. II.E.Montmorency, 1756-62 1761-romance and Nouvelle Heloise

- 52. II.E.Montmorency, 1756-62 Sophie d’Houdetot (27) & J-JR (45) she was his inspiration and anything more?? 1761-romance and Nouvelle Heloise The original title of The New Heloise, a European best-selling “bodice ripper”

- 53. II.E.Montmorency, 1756-62 1761-romance and Nouvelle Heloise 1762-Émile; Ou de l’Éducation “follow nature” progressive dogmas

- 55. blowup He resented being at Mme d'Épinay's beck and call and detested the insincere conversation and shallow atheism of the Encyclopédistes whom he met at her table. Wounded feelings gave rise to a bitter three-way quarrel between Rousseau and Madame d'Épinay; her lover, the philologist Grimm; and their mutual friend, Diderot, who took their side against Rousseau. Diderot later described Rousseau as being, "false, vain as Satan, ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical, and wicked ... He sucked ideas from me, used them himself, and then affected to despise me".

- 56. II. Writing A. Dijon competition, 1749 B. dropping out C. Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, 1755 D. Discourse on Political Economy, 1755 E. Montmorency, 1756-62 F. later life 1. proscriptions, exiles, and paranoia a. Switzerland b. England c. France 1. Confessions, 1770 2. peace at last, 1776-78

- 57. II.F.-later life; 1762-1778 Rousseau spoke of "the cry of unparalleled fury" that went up across Europe. "I was an infidel, an atheist, a lunatic, a madman, a wild beast, a wolf ..."

- 58. II.F.-later life; 1762-1778 Rousseau spoke of "the cry of unparalleled fury" that went up across Europe. "I was an infidel, an atheist, a lunatic, a madman, a wild beast, a wolf ..." after the bombshell of The Social Contract proscriptions, exiles & paranoia Geneva, Bern, Paris, England, return to France under an assumed name 1765-David Hume “You don’t know your man. I will tell you plainly, you are nursing a viper in your bosom-Baron d’Holbach “This lover of mankind who orphans his own children-Voltaire 1770-Confessions, forbidden to publish, he gave private readings-- Mme d’Épinay enjoined publication until 1782 1776-78-peace at last Ermenonville-a place of pilgrimage for his disciples

- 59. II.F.-later life; 1762-1778 after the bombshell of The Social Contract proscriptions, exiles & paranoia 1765-David Hume “You don’t know your man. I will tell you plainly, you are nursing a viper in your bosom-Baron d’Holbach “This lover of mankind who orphans his own children-Voltaire 1770-Confessions, forbidden to publish, he gave private readings--Mme d’Épinay enjoined publication until 1782 1776-78-peace at last painting by Hubert Robert, 1780 Ermenonville-a place of he also landscaped the park & designed the cenotaph pilgrimage for his disciples

- 60. The Parc de Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the garden of René Louis de Girardin, “Rousseau’s last pupil,” his host at Ermenonville

- 61. Joseph II Gustav III Paul I Franklin Jefferson The tomb and the garden became a destination of pilgrimage for admirers of Rousseau, including Joseph II of Austria, King Gustav III of Sweden, the future Czar Paul I of Russia, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Danton, Robespierre, Chateaubriand, Queen Marie Antoinette and Napoleon Bonaparte. Danton Robespierre Chateaubriand Antoinette Bonaparte

- 62. for Rousseau, immortal glory; 1794 Sixteen years after his death, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794, where they are located directly across from those of his friend-turned-enemy, Voltaire. His tomb, in the shape of a rustic temple, on which, in bas relief an arm reaches out, bearing the torch of liberty, evokes Rousseau's deep love of nature and of classical antiquity.

- 63. Du contrat social 1762

- 64. 1762

- 65. The Social Contract is, as Rousseau explains in his preface, a fragment of something much more ambitious -- a comprehensive work on Institutions politiques which he began to write in 1743 [during his disastrous time in Venice, “his first intimate acquaintance with politics and government”], but never finished. Maurice Cranston, trans.,Rousseau; The Social Contract, 1968. p. 9

- 66. Bk I Chapter I Subject of the First Book First Paragraph “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains “One thinks himself the master of others, and still remains a greater slave than they “How did this change come about? “I do not know “What can make it legitimate? “That question I think I can answer.”

- 67. III. Du contrat social, 1762; bks., IV, pp. 52 (Great Books ed.) A. Bk. I. “any sure and legitimate rule of administration”? 1. “men as they are and laws as they might be” 2. force and right 3. the “first convention” a. one or two contracts? CAUTION (III, 16) 4. key problem 5. who is the sovereign? a. fundamental law? b. “forced to be free” B. Bk. II. “important deduction [s]” 1. representative democracy? 2. three types of will a. particular will b. general will (Volonté Général) c will of all 3. role of association

- 68. III.A.1-3 After this brilliant opening paragraph, Rousseau develops his solution to the problem of tyranny promising to describe “men as they are and laws as they might be.” In Chapter III he rejects the notion of “the right of the strongest” by contrasting the terms “force” and “right.” In Bk. I, Chap. 5, THAT WE MUST ALWAYS GO BACK TO A FIRST CONVENTION, Rousseau seems to be following Locke in having a two-stage compact; first forming “a people,” then establishing a political compact. But in Bk. III, Chap. 16,THAT THE INSTITUTION OF GOVERNMENT IS NOT A CONTRACT, he asserts,”There is only one contract in the state: that of the association itself. jbp

- 69. III.A.4-key problem BOOK I CHAPTER VI THE SOCIAL COMPACT The problem is to find a form of association which will defend and protect with the whole common force the person and goods of each associate, and in which each, while uniting himself with all, may still obey himself alone, and remain as free as before. This is the fundamental problem of which the Social Contract provides the solution… These clauses, properly understood, may be reduced to one--the total alienation of each associate, together with all his rights, to the whole community; for in the first place, as each gives himself absolutely, the conditions are the same for all; and, this being so, no one has any interest in making them burdensome to others...

- 70. III.A.5. Finally, each man, in giving himself to all, gives himself to nobody; and as there is no associate over which he does not acquire the same right as he yields others over himself, he gains an equivalent for everything he loses, and an increase of force for the preservation of what he has. If then we discard from the social contract what is not of its essence, we shall find that it reduces itself to the following terms: Each of us puts his person and a! his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will, and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole. At once, in place of the individual personality of each contracting party, this act of association creates a moral and collective body….

- 71. III.A.5. b-”...forced to be free….” In order then that the social contract may not be a empty formula, it tacitly includes the undertaking, which alone can give force to the rest, that whosoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the whole body. This means nothing less than that he will be forced to be free [emphasis added] ….obedience to a law which we prescribe to ourselves is liberty.

- 72. III.B.1-representative democracy? BOOK II CHAPTER I THAT SOVEREIGNTY IS UNALIENABLE The first and most important deduction from the principles we have so far laid down is that the general will alone can direct the State according to the object for which it was instituted, i.e., the common good: for if the clashing of particular interests make the establishment of societies necessary, the agreement of these very interests made it possible…. I hold then that Sovereignty, being nothing less than the exercise of the general will, can never be alienated, and that the Sovereign, who is no less that a collective being, cannot be represented except by himself : the power indeed may be transmitted, but not the will. apparently not

- 73. III.B.2-three types of will BOOK II CHAPTER III WHETHER THE GENERAL WILL IS FALLIBLE It follows from what has gone before that the general will is always right and tends to the public advantage; but it does not follow that the deliberations of the people are always equally correct. Our will is always for our own good; but we do not always see what that is; the people is never corrupted, but it is often deceived, and on such occasions only does it seem to will what is bad. There is often a great deal of difference between the will of all and the general will; the latter considers only the common interest, while the former takes private interest into account, and is no more than the sum of the particular wills; but take away from these same wills the plusses and minuses that cancel one another, and the general will remains as the sum of the differences.

- 74. Now what can this mean? III.B.2.a. the particular will=the will of each individual III.B.2.b. the general will=”the sum of the differences” when one takes away “the plusses and minuses” of the particular wills “that cancel one another”--whatever that could mean in real life!!! And we are assured that the general will “is always right and tends to the public advantage” III.B.2.c. the will of all=something that “takes private interest into account” and, if it is the product of what he has called “the deliberations of the people,” it is fallible, unlike the general will Since these concepts are crucial to his argument, we are entitled to be worried about what seems to be mystification or fuzzy thinking here!

- 75. III.B.3-the role of associations BOOK II CHAPTER III WHETHER THE GENERAL WILL IS FALLIBLE (cont. from the same spot) If when the people, being furnished with adequate information, held its deliberations, had no communication one with another, the grand total of the small differences would always give the general will, and the decision would always be good. But when factions arise, and partial associations are formed at the expense of the great association, the will of each of these associations becomes general in relation to its members, while it remains particular in relation to the State : it may then be said that there are no longer as many votes as there are men, but only as many as there are associations. The differences become less numerous and give a less general result. Lastly, when one of these (cont.)

- 76. III.B.3-the role of associations BOOK II CHAPTER III WHETHER THE GENERAL WILL IS FALLIBLE (cont. from the same spot) and give a less general result. Lastly, when one of these (cont.) associations is so great as to prevail over all the rest, the result is no longer a sum of small differences, but a single difference; in this case there is no longer a general will, and the opinion which prevails is purely particular. It is there fore essential, if the general will is to be able to express itself, that there should be no partial society within the State, and that each citizen should think only his own thoughts: which was indeed the sublime and unique system established by the great Lycurgus [of Sparta]. But if there are partial societies, it is best to have as many as possible and to prevent them from being unequal as was done by Solon….These precautions are the only ones that can guarantee that the general will shall always be enlightened, and that the people shall in no way deceive itself….

- 77. III. Du contrat social, 1762; bks., IV, pp. 52 (Great Books ed.) A. Bk. I. “any sure and legitimate rule of administration”? B. Bk. II “important deduction [s]” C. Bk III “different forms” 1. force and will in the body politic a. what is government? 2. historical and geographic factors a. Projet de constitution pour la Corse, 1765 b. Considerations sur le gouvernement de la Pologne, 1770 (?) 3. tendency to degenerate a. civic virtue and deputies D. Bk IV the ultimate foundation of authority 1. voting 2. historical discussion on Rome 3. civil religion

- 78. III.C.1-force and will in the body politic BOOK III CHAPTER I GOVERNMENT IN GENERAL I warn the reader that this chapter requires careful reading, and that I am unable to make myself clear to those who refuse to be attentive. Every free action is produced by the concurrence of two causes: one moral, i.e. the will which determines the act; the other physical, i.e. the power which executes it. I walk towards an object, it is necessary first that I should will to go there, and, in the second place, that my feet should carry me. If a paralytic wills to run and an active man wills not to, they will both stay where they are. The body politic has the same motive powers; here too force and will are distinguished, will under the name of legislative power, and force under that of executive power. Without their concurrence, nothing is, or should be, done. (continued)

- 79. III.C.1-force and will in the body politic BOOK III CHAPTER I GOVERNMENT IN GENERAL concurrence, nothing is, or should be, done. (continued) We have seen that the legislative power belongs to the people, and can belong to it alone. It may on the other hand, readily be seen, from the principles laid down above, that the executive power cannot belong to the generality as the legislature or Sovereign, whose acts must always be laws. The public force therefore needs an agent of its own to bind it together and set it to work under the direction of the general will, to serve as a means of communication between the State and the Sovereign, and to do for the collective person more or less what the union of soul and body does for men. Here we have what is, in the State, the basis of government, often wrongly confused with the Sovereign, whose minister it is. (continued)

- 80. III.C.1-force and will in the body politic a. what is government? BOOK III CHAPTER I GOVERNMENT IN GENERAL it is. (continued) What then is government? An intermediate body set up between the subjects and the Sovereign, to secure their mutual correspondence, charged with the execution of the laws and the maintenance of liberty, both civil and political. The members of this body are called magistrates or kings, that is to say governors, and the whole body bears the name of prince. Thus those that hold that the act, by which a people puts itself under a prince, is not a contract, are certainly right. It is simply and solely a commission, an employment, in which the rulers, mere officials of the Sovereign, exercise in their own name the power of which it makes them depositaries. This power it can limit, modify, or recover at pleasure; for the alienation of such a right is incompatible with the nature of the social body, and contrary to the end of association. (continued)

- 81. III.C.1-force and will in the body politic a. what is government? BOOK III CHAPTER I GOVERNMENT IN GENERAL contrary to the end of association. (continued) I call then government, or supreme administration, the legitimate exercise of the executive power, and prince or magistrate the man or body entrusted with that administration. In government reside the intermediate forces whose relations make up that of the whole to the whole or of the Sovereign to the State. This last relation may be represented as that between the extreme terms of a continuous proportion, which has government as its mean proportional.

- 82. Diagram of this mathematical analogy Sovereign Government (all the people) = Government State or (all the people) Sovereign State : Government :: Government : (all the people) (all the people) Whatever this might mean!!!

- 83. III.C.1-force and will in the body politic a. what is government? continuous proportion, which has government as its mean proportional. The government gets from the Sovereign the orders it gives the people, and, for the State to be properly balanced, there must, when everything is reckoned in, be equality between the product or power of the government taken in itself, and the product or power of the citizens, who are on the one hand sovereign and on the other subject. Furthermore, none of these three terms can be altered without the equality being instantly destroyed. If the Sovereign desires to govern, or the magistrate to give laws, or if the subjects refuse to obey, disorder takes the place of regularity, force and will no longer act together, and the State is dissolved and falls into despotism or anarchy. Lastly, as there is also only one mean proportional between each relation, there is also only one good government possible for a State. But, as countless events may change the relations of a people, not only may different governments be good for different people, but also for the same people at different times….

- 84. III.C.2-historical & geographic factors a. Projet de constitution pour la Corse, 1765 b. Considerations sur le gouvernement de la Pologne, 1770 (?) In 1762, as a political philosopher, Rousseau wrote the sentence above, that “different governments may be good for different people.” In the next decade, as a political scientist, he would try his hand at this very task. Clearly influenced by Montesquieu’s geographic approach, Rousseau responded to requests from these two countries, Corsica and Poland. Both were tottering on the brink of conquest and the extinction of self-government; Corsica by France, Poland by Prussia, Russia, and Austria. These attempts to apply the ideas of the Social Contract to real life situations shed an interesting light on Rousseau’s thinking, often at odds with his more idealistic musings in 1762.

- 85. III.C.3-tendency to degenerate A constant theme in his thought, beginning with the first discourse in 1749, was how civilization tended to corrupt man’s natural goodness.--jbp BOOK III CHAPTER X THE ABUSE OF GOVERNMENT AND ITS TENDENCY TO DEGENERATE As the particular will acts constantly in opposition to the general will, the government continually exerts itself against the Sovereignty. The greater this exertion becomes, the more the constitution changes; and as there is in this case no other corporate will to create an equibrilum by resisting the will of the prince, sooner or later the prince must inevitably suppress the Sovereign and break the social treaty. This is the unavoidable and inherent defect which, from the very birth of the body politic, tends to destroy it, as age and death end by destroying the human body….

- 86. III.C.3-tendency to degenerate a. civic virtue and deputies When citizens replace civic virtue with greed for a comfortable life, they hire deputies to govern for them--jbp BOOK III CHAPTER XV DEPUTIES OR REPRESENTATIVES As soon as public service ceases to be the chief business of the citizens and they would rather serve with their money than with their persons, the State is not far from its fall. When it is necessary to march out to war, they pay troops and stay at home: when it is necessary to meet in council, they name deputies and stay at home. By reason of idleness and money, they end by having soldiers to enslave their country and representatives to sell it. (continued)

- 87. III.C.3-tendency to degenerate a. civic virtue and deputies BOOK III CHAPTER XV DEPUTIES OR REPRESENTATIVES and representatives to sell it. (continued) It is through the hustle of commerce and the arts, through the greedy self-interest of profit, and through softness and love of amenities that personal services are replaced by money payments. Men surrender a part of their profits in order to have time to increase them at leisure. Make gifts of money, and you will not be long without chains…. ….In a well-ordered city every man flies to the assemblies: under a bad government no one cares to stir a step to get to them, because no one is interested in what happens there, because it is foreseen that the general will will not prevail, and lastly because domestic cares are all-absorbing…. As soon as any man says of the affairs of the State What does it matter to me? the State may be given up for lost….

- 88. III.D.-the ultimate foundation of authority 1. voting 2. historical discussion on Rome 3. civil religion In Chapter I of this final book Rousseau’s idealization of Swiss public assemblies is clearly observable. “When we see among the happiest people in the world bands of peasants regulating the affairs of state under an oak tree, and always acting wisely, can we help feeling a certain contempt for the refinements of other nations, which employ so much skill and mystery to make themselves at once illustrious and wretched?” In Chapters 2 & 3 he attempts to relate voting to the discovery of the general will. In Chapters 4-7 he reviews the political history of Rome and its pursuit of the general will. In Chapter 8, “The Civil Religion,” he reviews the history of religious strife and offers a vision of a unifying patriotic faith which would bind men to their civic duty towards the State.

- 89. III.D.3-civil religion BOOK IV CHAPTER VIII THE CIVIL RELIGION ...But I err in speaking of a Christian republic; for each of these terms contradicts the other. Christianity preaches only servitude and submission. In spirit it is too favorable to tyranny for tyranny not to take advantage of it. True Christians are made to be slaves; they know it and they hardly care; this short life has too little value in their lives…. There is thus a profession of faith which is purely civil and of which it is the sovereign’s function to determine the articles, not strictly as religious dogmas, but as sentiments of sociability, without which it is impossible to be either a good citizen or a loyal subject.... The dogmas of the civil religion must be simple and few in number, expressed precisely and without explanations or commentaries. (cont.)

- 90. III.D.3-civil religion BOOK IV CHAPTER VIII THE CIVIL RELIGION expressed precisely and without explanations or commentaries. (cont.) The existence of an omnipotent, intelligent, benevolent divinity that foresees and provides; the life to come; the happiness of the just; the punishment of sinners; the sanctity of the social contract and the law --- these are the positive dogmas. As for the negative dogmas, I would limit them to a single one: no intolerance. Intolerance is something which belongs to the religions we have rejected.

- 91. Criticism

- 92. VOLTAIRE BENJAMIN CONSTANT JOHN CRAWFURD CHARLES MAURRAS 1694-1778 1767-1830 1783-1868 1868-1952 Criticism SIR KARL POPPER HANNAH ARENDT ROBERT PALMER MAURICE CRANSTON 1902-1994 1906-1975 1909-2002 1920-1993

- 93. IV. Criticism A. Historical Critics 1. 18th century 2. 19th century 3. 20th century B. Criticism from Justice & Power, 1977 1. Robespierre and post hoc ergo propter hoc 2. argumentum ad hominem 3. Sparta and civic virtue 4. totalitarian democracy?

- 94. Although Rousseau was wildly popular during his lifetime and especially after his death and during the Revolution, criticism dogged him beginning with those who had begun as his friends. The first to criticize Rousseau were his fellow Philosophes, above all, Voltaire. According to Jacques Barzun: Voltaire, who had felt annoyed by the first essay [On the Arts and Sciences], was outraged by the second, [Discourse on the Origin of Inequality Among Men], declaring that Rousseau wanted us to “walk on all fours” like animals and behave like savages, believing them creatures of perfection. From these interpretations, plausible but inexact, spring the clichés Noble Savage and Back to Nature. Wikipedia After receiving the Second Discourse he wrote, “I have received, Monsieur, your new book against the human race, and I thank you.” After the famous passage about the first man to enclose property, he wrote “Behold the philosophy of a beggar who would have the rich robbed by the poor.” Of his forty-one marginal notes, forty are critical.--quotes in Cranston, Inequality jbp

- 95. Following the French Revolution, other commentators fingered a potential danger of Rousseau’s project of realizing an “antique” conception of virtue amongst the citizenry in a modern world (e.g. through education, physical exercise, a citizen militia, public holidays, and the like). Taken too far, as under the Jacobins, such social engineering could result in tyranny. As early as 1819, in his famous speech “On Ancient and Modern Liberty,” the political philosopher Benjamin Constant, a proponent of constitutional monarchy and representative democracy, criticized Rousseau, or rather his more radical followers (specifically the Abbé de Mably), for allegedly believing that "everything should give way to collective will, and that all restrictions on individual rights would be amply compensated by participation in social power.” Wikipedia

- 96. Common also were attacks by defenders of social hierarchy on Rousseau's "romantic" belief in equality. In 1860, shortly after the Sepoy Rebellion in India, two British white supremacists, John Crawfurd and James Hunt, mounted a defense of British imperialism based on “scientific racism". Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, took over the presidency of the British Anthropological Society, which had been founded with the mission to defend indigenous peoples against slavery and colonial exploitation. Invoking "science" and "realism", the two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing that mankind was divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity.'" For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Since Crawfurd was Scottish, he thought the Scottish "race" superior and all others inferior; whilst Hunt, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon "race". Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau’s Noble Savage". (The pair ultimately quarreled because Hunt believed in slavery and Crawfurd did not). "As Ter Ellingson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau.” Wikipedia

- 97. Common also were attacks by defenders of social hierarchy on Rousseau's "romantic" belief in equality. In 1860, shortly after the Sepoy Rebellion in India, two British white supremacists, John Crawfurd and James Hunt, mounted a defense of British imperialism based on “scientific racism". Crawfurd, in alliance with Hunt, took over the presidency of the British Anthropological Society, which had been founded with the mission to defend indigenous peoples against slavery and colonial exploitation. Invoking "science" and "realism", the two men derided their "philanthropic" predecessors for believing in human equality and for not recognizing that mankind was divided into superior and inferior races. Crawfurd, who opposed Darwinian evolution, "denied any unity to mankind, insisting on immutable, hereditary, and timeless differences in racial character, principal amongst which was the 'very great' difference in 'intellectual capacity.'" For Crawfurd, the races had been created separately and were different species. Since Crawfurd was Scottish, he thought the Scottish "race" superior and all others inferior; whilst Hunt, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon "race". Crawfurd and Hunt routinely accused those who disagreed with them of believing in "Rousseau’s Noble Savage". (The pair ultimately quarreled because Hunt believed in slavery and Crawfurd did not). "As Ter Ellingson demonstrates, Crawfurd was responsible for re-introducing the Pre-Rousseauian concept of 'the Noble Savage' to modern anthropology, attributing it wrongly and quite deliberately to Rousseau.”

- 98. Karl Popper was the modern critic whom we met last fall as a critic of Plato. He also lists Rousseau as an Enemy of the Open Society. Popper sees the General Will as a foreshadowing of twentieth century totalitarianism. He equates Robespierre’s version of Rousseau with Lenin’s version of Marx and Hitler’s version of his own twisted ideas in Mein Kampf.

- 99. During the Cold War, Karl Popper criticized Rousseau for his association with nationalism and its attendant abuses. This came to be known among scholars as the "totalitarian thesis". An example is J. L. Talmon's, The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy (1952). Political scientist J. S. Maloy states that “the twentieth century added Nazism and Stalinism to Jacobinism on the list of horrors for which Rousseau could be blamed. ... Rousseau was considered to have advocated just the sort of invasive tampering with human nature which the totalitarian regimes of mid-century had tried to instantiate." But Maloy adds that "The totalitarian thesis in Rousseau studies has, by now, been discredited as an attribution of real historical influence.” Wikipedia

- 100. In 1919 Irving Babbitt, founder of a movement called the "New Humanism", wrote a critique of what he called "sentimental humanitarianism", for which he blamed Rousseau. Babbitt's depiction of Rousseau was countered in a celebrated and much reprinted essay by A. O. Lovejoy in 1923. In France, fascist theorist and anti-Semite Charles Maurras, founder of Action Française, “had no compunctions in laying the blame for both Romantisme et Révolution firmly on Rousseau in 1922." Wikipedia

- 101. In 1919 Irving Babbitt, founder of a movement called the "New Humanism", wrote a critique of what he called "sentimental humanitarianism", for which he blamed Rousseau. Babbitt's depiction of Rousseau was countered in a celebrated and much reprinted essay by A. O. Lovejoy in 1923. In France, fascist theorist and anti-Semite Charles Maurras, founder of Action Française, “had no compunctions in laying the blame for both Romantisme et Révolution firmly on Rousseau in 1922." Wikipedia

- 102. On similar grounds, one of Rousseau's strongest critics during the second half of the 20th century was political philosopher Hannah Arendt. Using Rousseau's thought as an example, Arendt identified the notion of sovereignty with that of the general will. According to her, it was this desire to establish a single, unified will based on the stifling of opinion in favor of public passion that contributed to the excesses of the French Revolution. Wikipedia

- 103. On similar grounds, one of Rousseau's strongest critics during the second half of the 20th century was political philosopher Hannah Arendt. Using Rousseau's thought as an example, Arendt identified the notion of sovereignty with that of the general will. According to her, it was this desire to establish a single, unified will based on the stifling of opinion in favor of public passion that contributed to the excesses of the French Revolution.

- 104. And what, in summary, was likely in his book to appeal to men in a mood of rebellion…? First of all, the theory of the political community, of the people, or nation, was revolutionary in implication: it posited a community based on the will of the living, and the active sense of membership…, rather than on history, or kinship, or race, or past conquest…. It denied sovereign powers to kings, to oligarchs, and to all governments. It said that any form of government could be changed. It held all public officers to be removable. It held that law could draw its force and its legality only from the community itself…. Not only monarchs, but also the constituted bodies…, would be justified in believing that the Social Contract sapped their foundations. R. R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution. vol. 1, pp. 126-127

- 105. In less than a hundred pages, Rousseau outlined a theory of evolution of the human race which prefigured the discoveries of Darwin; he revolutionized the study of anthropology and linguistics, and he made a seminal contribution to political and social thought….it altered people’s ways of thinking about themselves and their world; it even changed their ways of feeling. Of all his writings, Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality...has perhaps been the most influential. The books of his later years...are more ‘substantial’, but it is as the author of the second Discourse that Rousseau has both been held responsible for the French Revolution and acclaimed as the founder of modern social science. Maurice Cranston, Rousseau; A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, 1984. p. 29

- 106. IV. Criticism A. Historical Critics B. Criticism from Justice & Power, 1977 1. Robespierre and post hoc ergo propter hoc 2. argumentum ad hominem 3. Sparta and civic virtue 4. totalitarian democracy?

- 107. So what do we conclude? Herald of the Democratic Revolution in France? Dangerous romantic nationalist? A great deal of one’s reaction to Rousseau is bound up in one’s reaction to the French Revolution. Both have their admirable and not so admirable aspects. Much of our reaction is influenced by the wars of the Revolution and its successor Napoleon. A conservative voice warned of the bloodbath to come as early as 1790. But that’s another story… First, we’ll look back next week at our democratic revolution.