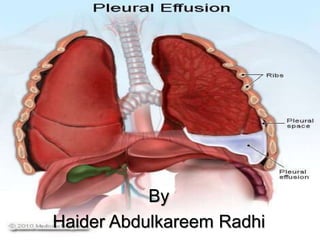

Pleural Effusiion

- 2. Background A pleural effusion is collection of fluid abnormally present in the pleural space, usually resulting from excess fluid production and/or decreased lymphatic absorption. It is the most common manifestation of pleural disease, and its etiologies range in spectrum from cardiopulmonary disorders and/or systemic inflammatory conditions to malignancy

- 3. Etiology The normal pleural space contains approximately 10 mL of fluid, representing the balance between (1) hydrostatic and oncotic forces in the visceral and parietal pleural capillaries and (2) persistent lymphatic drainage. Pleural effusions may result from disruption of this natural balance.

- 4. Presence of a pleural effusion indicate an underlying disease process that may be pulmonary or nonpulmonary in origin and, furthermore, that may be acute or chronic. Although the etiologic spectrum of pleural effusion can be extensive, most pleural effusions are caused by congestive heart failure, pneumonia, malignancy, or pulmonary embolism.

- 5. Mechanisms * Altered permeability of the pleural membranes (eg, inflammation, malignancy, pulmonary embolism) * Reduction in intravascular oncotic pressure (eg, hypoalbuminemia due to nephrotic syndrome or cirrhosis) * Increased capillary permeability or vascular disruption (eg, trauma, malignancy, inflammation, infection, pulmonary infarction, drug hypersensitivity, uremia, pancreatitis) * Increased capillary hydrostatic pressure in the systemic and/or pulmonary circulation (eg, congestive heart failure, superior vena cava syndrome) * Reduction of pressure in the pleural space (ie, due to an inability of the lung to fully expand during inspiration); this is known as "trapped lung" (eg, extensive atelectasis due to an obstructed bronchus or contraction from fibrosis leading to restrictive pulmonary physiology)

- 6. * Decreased lymphatic drainage or complete lymphatic vessel blockage, including thoracic duct obstruction or rupture (eg, malignancy, trauma) * Movement of fluid from pulmonary edema across the visceral pleura * Persistent increase in pleural fluid oncotic pressure from an existing pleural effusion, causing further fluid accumulation

- 7. Pleural effusions are generally classified as transudates or exudates, based on the mechanism of fluid formation and pleural fluid chemistry. Transudates result from an imbalance of oncotic and hydrostatic pressures, whereas exudates are the result of inflammatory processes of the pleura and/or decreased lymphatic drainage. In some cases, it is not rare for pleural fluid to exhibit mixed characteristics of transudate and exudate.

- 8. Transudate Transudates are caused by a small, defined group of etiologies, including the following: Congestive heart failure Cirrhosis (hepatic hydrothorax) Atelectasis (may be due to occult malignancy or pulmonary embolism) Hypoalbuminemia Nephrotic syndrome Peritoneal dialysis Constrictive pericarditis Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks to the pleura (in the setting of ventriculopleural shunting or of trauma/surgery to the thoracic spine) Extravascular migration of central venous catheter

- 9. Exudates • Produced by a variety of inflammatory conditions (and often requiring a more extensive evaluation and treatment strategy than transudates), exudative effusions develop from inflammation of the pleura or from decreased lymphatic drainage at pleural edges. • Mechanisms of exudative formation include pleural or parenchymal inflammation, impaired lymphatic drainage of the pleural space, altered permeability of pleural membranes, and/or increased capillary wall permeability or vascular disruption. Pleural membranes are involved in the pathogenesis of the fluid formation. Of note, the permeability of pleural capillaries to proteins is increased in disease states with elevated protein content.

- 10. The more common causes of exudates include the following: Parapneumonic causes Malignancy (most commonly lung or breast cancer, lymphoma, and leukemia; less commonly ovarian carcinoma, stomach cancer, sarcomas, melanoma) [9] Pulmonary embolism Collagen-vascular conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus Tuberculosis (TB) Pancreatitis Trauma Esophageal perforation Sarcoidosis Pericardial disease Uremia Chylothorax (acute illness with elevated triglycerides in pleural fluid) Fistula (ventriculopleural, biliopleural, gastropleural)

- 12. Distinguishing Transudates From Exudates • The initial diagnostic consideration is distinguishing transudates from exudates. Although a number of chemical tests have been proposed to differentiate pleural fluid transudates from exudates, the tests first proposed by Light et al have become the criterion standards. • The fluid is considered an exudate if any of the following are found: • Ratio of pleural fluid to serum protein greater than 0.5 • Ratio of pleural fluid to serum LDH greater than 0.6 • Pleural fluid LDH greater than two thirds of the upper limits of normal serum value

- 13. Pleural Effusion Clinical Presentation Some patients with pleural effusion have no symptoms, with the condition discovered on a chest x-ray that is performed for another reason. The patient may have unrelated symptoms due to the disease or condition that has caused the effusion . Symptoms of pleural effusion include: Chest pain Dry, nonproductive cough Dyspnea Orthopnea (the inability to breathe easily unless the person is sitting up straight or standing erect)

- 14. Physical Examination Physical findings in pleural effusion are variable and depend on the volume of the effusion. Typically, there are no clinical findings for effusions less than 300 mL. With effusions greater than 300 mL, chest wall/pulmonary findings may include the following: Dullness to percussion, and asymmetrical chest expansion, with diminished or delayed expansion on the side of the effusion: These are the most reliable physical findings of pleural effusion. Mediastinal shift away from the effusion: This finding is observed with effusions greater than 1000 mL. Displacement of the trachea and mediastinum toward the side of the effusion is an important clue to obstruction of a lobar bronchus by an endobronchial lesion, which can be due to malignancy or, less commonly, to a nonmalignant cause, such as a foreign body obstruction. Diminished or inaudible breath sounds Pleural friction rub

- 15. Other physical and extrapulmonary findings may suggest the underlying cause of the pleural effusion. Peripheral edema, distended neck veins, and S3 gallop suggest congestive heart failure. Edema may also be a manifestation of nephrotic syndrome or pericardial disease . Cutaneous changes and ascites suggest liver disease. Lymphadenopathy or a palpable mass suggests malignancy.

- 16. Approach Considerations Thoracentesis should be performed for new and unexplained pleural effusions when sufficient fluid is present to allow a safe procedure. Observation of pleural effusion is reasonable when benign etiologies are likely, as in the setting of overt congestive heart failure, viral pleurisy, or recent thoracic or abdominal surgery. Laboratory testing helps to distinguish pleural fluid transudates from exudates. However, certain types of exudative pleural effusions might be suspected simply by observing the gross characteristics of the fluid obtained during thoracentesis. Note the following:

- 17. Frankly purulent fluid indicates an empyema A putrid odor suggests an anaerobic empyema A milky, opalescent fluid suggests a chylothorax, resulting most often from lymphatic obstruction by malignancy or thoracic duct injury by trauma or surgical procedure Grossly bloody fluid may result from trauma, malignancy or asbestos-related effusion and indicates the need for a spun hematocrit test of the sample. A pleural fluid hematocrit level of more than 50% of the peripheral hematocrit level defines a hemothorax, which often requires tube thoracostomy

- 18. Normal pleural fluid Normal pleural fluid has the following characteristics: Clear ultrafiltrate of plasma that originates from the parietal pleura A pH of 7.60-7.64 Protein content of less than 2% (1-2 g/dL) Fewer than 1000 white blood cells (WBCs) per cubic millimeter Glucose content similar to that of plasma Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) less than 50% of plasma

- 19. Pleural Fluid LDH, Glucose, and pH Pleural fluid LDH • Pleural fluid LDH levels greater than 1000 IU/L suggest empyema, malignant effusion, rheumatoid effusion. Pleural fluid LDH levels are also increased in effusions from Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly, P carinii) pneumonia. The diagnosis is suggested by a pleural fluid/serum LDH ratio of greater than 1, with a pleural fluid/serum protein ratio of less than 0.5.

- 20. Pleural fluid glucose and pH • In addition to the previously discussed tests, glucose and pleural fluid pH should be measured during the initial thoracentesis in most situations. • A low pleural glucose concentration (30-50 mg/dL) suggests malignant effusion, tuberculous pleuritis, esophageal rupture, or lupus pleuritis. A very low pleural glucose concentration (ie, < 30 mg/dL) further restricts diagnostic possibilities, to rheumatoid pleurisy or empyema.

- 21. • Pleural fluid pH is highly correlated with pleural fluid glucose levels. A pleural fluid pH of less than 7.30 with a normal arterial blood pH level is caused by the same diagnoses as listed above for low pleural fluid glucose. However, for parapneumonic effusions, a low pleural fluid pH level is more predictive of complicated effusions (that require drainage) than is a low pleural fluid glucose level. In such cases, a pleural fluid pH of less than 7.1-7.2 indicates the need for urgent drainage of the effusion, while a pleural fluid pH of more than 7.3 suggests that the effusion may be managed with systemic antibiotics alone. • In malignant effusions, a pleural fluid pH of less than 7.3 has been associated in some reports with more extensive pleural involvement, higher yield on cytology, decreased success of pleurodesis, and shorter survival times

- 22. Pleural Fluid Cell Count Differential • If an exudate is suspected clinically or is confirmed by chemistry test results, send the pleural fluid for total and differential cell counts, Gram stain, culture, and cytology. • Pleural fluid lymphocytosis, with lymphocyte values greater than 85% of the total nucleated cells, suggests TB, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, chronic rheumatoid pleurisy, and chylothorax. Pleural lymphocyte values of 50-70% of the nucleated cells suggest malignancy.

- 23. • Pleural fluid eosinophilia (PFE), with eosinophil values greater than 10% of nucleated cells, is seen in approximately 10% of pleural effusions and is not correlated with peripheral blood eosinophilia. PFE is most often caused by air or blood in the pleural space. Blood in the pleural space causing PFE may be the result of pulmonary embolism with infarction or benign asbestos pleural effusion. PFE may be associated with other nonmalignant diseases, including parasitic disease , fungal infection and a variety of medications.

- 24. Pleural Fluid Culture and Cytology • Cultures of infected pleural fluids yield positive results in approximately 60% of cases. This occurs even less often for anaerobic organisms. Diagnostic yields, particularly for anaerobic pathogens, may be increased by directly culturing pleural fluid into blood culture bottles. • Malignancy is suspected in patients with known cancer or with lymphocytic, exudative effusions, especially when bloody. Direct tumor involvement of the pleura is diagnosed most easily by performing pleural fluid cytology

- 25. Chest Radiography • Effusions of more than 175 mL are usually apparent as blunting of the costophrenic angle on upright posteroanterior chest radiographs. On supine chest radiographs, which are commonly used in the intensive care setting, moderate to large pleural effusions may appear as a homogenous increase in density spread over the lower lung fields. Apparent elevation of the hemidiaphragm, lateral displacement of the dome of the diaphragm, or increased distance between the apparent left hemidiaphragm and the gastric air bubble suggests subpulmonic effusions.

- 30. Diagnostic Thoracentesis • A diagnostic thoracentesis should be performed if the etiology of the effusion is unclear or if the presumed cause of the effusion does not respond to therapy as expected. Pleural effusions do not require thoracentesis if they are too small to safely aspirate or, in clinically stable patients, if their presence can be explained by underlying congestive heart failure (especially bilateral effusions) or by recent thoracic or abdominal surgery.

- 31. Contraindications • Relative contraindications to diagnostic thoracentesis include a small volume of fluid (< 1 cm thickness on a lateral decubitus film), bleeding diathesis or systemic anticoagulation, mechanical ventilation, and cutaneous disease over the proposed puncture site. Reversal of coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia may not be necessary as long as the procedure is performed under ultrasound guidance by an experienced operator. Mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure does not increase the risk of pneumothorax after thoracentesis, but it increases the likelihood of severe complications (tension pneumothorax or persistent bronchopleural fistula) if the lung is punctured. An uncooperative patient is an absolute contraindication for this procedure

- 32. Complications • Complications of diagnostic thoracentesis include pain at the puncture site, cutaneous or internal bleeding from laceration of an intercostal artery or spleen/liver puncture, pneumothorax, empyema, reexpansion pulmonary edema, malignant seeding of the thoracentesis tract, and adverse reactions to anesthetics used in the procedure. Pneumothorax complicates approximately 6% of thoracenteses but requires treatment with a chest tube drainage of the pleural space in less than 2% of cases

- 33. Biopsy • Pleural biopsy should be considered, only if TB or malignancy is suggested. Medical thoracoscopy with the patient under conscious sedation and local anesthesia has emerged as a diagnostic tool to directly visualize and take a biopsy specimen from the parietal pleura in cases of undiagnosed exudative effusions.

- 34. How is pleural effusion treated? • Treatment of pleural effusion is based on the underlying condition and whether the effusion is causing severe respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath or difficulty breathing. • Diuretics and other heart failure medications are used to treat pleural effusion caused by congestive heart failure or other medical causes. A malignant effusion may also require treatment with chemotherapy, radiation therapy or a medication infusion within the chest. • A pleural effusion that is causing respiratory symptoms may be drained using therapeutic thoracentesis or through a chest tube (called tube thoracostomy).

- 35. • For patients with pleural effusions that are uncontrollable or recur due to a malignancy despite drainage, a sclerosing agent (a type of drug that deliberately induces scarring) occasionally may be instilled into the pleural cavity through a tube thoracostomy to create a fibrosis (excessive fibrous tissue) of the pleura (pleural sclerosis). • Pleural sclerosis performed with sclerosing agents (such as talc, doxycycline, and tetracycline) is 50 percent successful in preventing the recurrence of pleural effusions.

- 36. Surgery • Pleural effusions that cannot be managed through drainage or pleural sclerosis may require surgical treatment. • The two types of surgery include: Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) Thoracotomy (Also referred to as traditional, “open” thoracic surgery)