Kessuud Process Model2.1

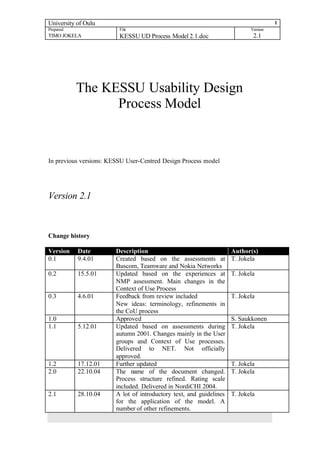

- 1. University of Oulu 1 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 The KESSU Usability Design Process Model In previous versions: KESSU User-Centred Design Process model Version 2.1 Change history Version Date Description Author(s) 0.1 9.4.01 Created based on the assessments at T. Jokela Buscom, Teamware and Nokia Networks 0.2 15.5.01 Updated based on the experiences at T. Jokela NMP assessment. Main changes in the Context of Use Process 0.3 4.6.01 Feedback from review included T. Jokela New ideas: terminology, refinements in the CoU process 1.0 Approved S. Saukkonen 1.1 5.12.01 Updated based on assessments during T. Jokela autumn 2001. Changes mainly in the User groups and Context of Use processes. Delivered to NET. Not officially approved. 1.2 17.12.01 Further updated T. Jokela 2.0 22.10.04 The name of the document changed. T. Jokela Process structure refined. Rating scale included. Delivered in NordiCHI 2004. 2.1 28.10.04 A lot of introductory text, and guidelines T. Jokela for the application of the model. A number of other refinements.

- 2. University of Oulu 2 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Abstract A reference model of usability design, KESSU UD model, is proposed. Its original purpose is to be as a reference of usability design – “what exactly designing usability is” - in the assessement the user-centredness of development projects. It can be – and also has been - used for other purposes, such as planning of usability activities for new projects. A unique feature of the model is that it is method- independent, i.e. does not presume of using any specific usability technique. This document gives the background and defines the KESSU UD model. Further, guidelines are provided for how to use the model in planning usability activities, and in assessment of usability processes.

- 3. University of Oulu 3 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Contents ABSTRACT...............................................................................................2 CONTENTS ...............................................................................................3 1 FOREWORDS .................................................................................4 2 BACKGROUND ..............................................................................4 3 WHAT IS USABILITY? .................................................................5 4 OVERVIEW OF THE KESSU UD PROCESS MODEL ............6 5 USING THE MODEL IN PLANNING USABILITY DESIGN ..9 5.1 MAPPING USABILITY METHODS WITH THE MODEL ..........................10 5.2 HOW MUCH TO DO? ........................................................................10 5.3 IF USABILITY REQUIREMENTS ARE NOT M ET ................................11 5.4 BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN USABILITY DESIGN AND PRODUCT DESIGN 12 5.5 INTEGRATION WITH THE PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT LIFECYCLE ......12 6 USING THE MODEL IN THE ASSESSMENT OF USER- CENTRED DESIGN .....................................................................13 7 DISCUSSION .................................................................................14 7.1 LIMITATIONS ..................................................................................14 7.2 IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS ...............................................14 REFERENCES ........................................................................................15 APPENDIX 1: DEFINITIONS OF PROCESSES ...............................17 IDENTIFICATION OF USERS GROUPS .......................................................17 CONTEXT OF USE ANALYS IS ..................................................................17 USER REQUIREMENTS DETERMINATION ................................................18 USER TASK REDESIGN ...........................................................................19 USABILITY F EEDBACK ...........................................................................19 USABILITY VERIFICATION .....................................................................20 INTERACTION DESIGN ...........................................................................20 APPENDIX 2: PERFORMANCE ATTRIBUTES ..............................22

- 4. University of Oulu 4 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 1 Forewords This document describes the KESSU UD Process model for usability design1 , UD, that has been developed first in the national KESSU project (2000 – 2003) in Finland, and later in additional industrial trials. Published research papers, where the different versions of the model are described, are for example [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. The KESSU model has earlier versions. One version was published in Cutter IT Journal [8]. The version described in this document can be regarded as an updated version of the Cutter IT Journal article. The model can be regarded as a concrete interpretation of the user-centred design process models of ISO 13407 [10] and ISO/TR 18529 [11]. The interpretation means a more explicit definition of UD processes. We find it useful to have clear, unambiguous and sense- making definitions of usability design processes. 2 Background When we consider designing usability, our first impulse is typically to think about usability methods. When planning usability actions, we may debate whether to use personas, use cases, task analysis, usability testing, user scenarios, or paper prototyping. Or should we use a usability methodology that covers the different phases of development, such as Contextual Design [12] or the Usability Engineering Lifecycle [13]? The jungle of usability methods makes it difficult to plan and manage the usability design process. Which methods are appropriate for a specific product or system development 2 project? Do we need to conduct field studies and extensive usability tests, both of which consume a lot of time and money? How many cycles of iteration are required? What kind of user involvement is appropriate? What are the specific challenges or typical obstacles we should consider when implementing usability actions? We seem to forget that methods and methodologies are, by definition, just various means for achieving usability, not the fundamental things. To have a firmer basis for planning and managing the usability design process, we need a method- independent model of usability design, analogous to the lifecycle models used in software engineering. The KESSU UD model is such a model of usability design. Concretely, the KESSU model defines usability design through processes and outcomes. The outcomes should be produced as a result of usability activities, in order to make usability design systematic. Usability methods come second; they are the practical means for performing the processes and generating the outcomes. 1 We use the term ’usability design’ to emphasise that the focus of the model is to support designing good usability. Earlier we used the term ’user-centred design’. There is a slight difference in these concepts: ’usability’ is the ultimate goal while ’user-centredness’ is a means (among others such as iteration) for achieving good usability. 2 In this document, we mainly use the term ’product development’. The discussion, however, is meant to apply generally to software and system development.

- 5. University of Oulu 5 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 The original motivation for developing the model was a number of usability maturity assessments that we carried out in several product and system development organizations [14]. We found it necessary to have an objective model as a foundation for discussions with development staff — we could not require an organization to use any specific methods. We have since successfully used the model as a basis for usability project planning and for gene rally communicating the essence of usability to development managers and practitioners. 3 What is usability? The main theoretical source for the model is the standard definition of usability. Therefore, before I describe the model, let’s examine what exactly usability is. The definition of usability from ISO 9241-11 [15] is: “the extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use.” This definition is not only a formal standard but is also becoming the de facto standard. For example, this definition is used in the recent Common Industry Format for usability testing [16], which was supported by a number of major corporations and other organizations. The definition means, first of all, that usability is not an absolute product property but always exists in relation to the users of the product (specified users). In other words, a product can be usable to some users but unusable to others. For each user, usability is further a function of achieving goals in defined environments of use. Finally, usability is a measurable characteristic defined through three attributes: effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction. As an example, the usability measures for an automated teller machine (ATM) might include the following: “90% [effectiveness] of 7 novices [specified users] can withdraw a desired sum of cash [specified goal] in less than one minute [efficiency] with an average satisfaction rating ‘6’ on an ordinal scale 1-7 [satisfaction] with any ATM [environment of use].” Any product typically has several different user groups. Some of the goals are shared by more than one user group; some user groups may have unique goals. When the types of users and environments of use differ, the levels of usability measures typically differ, too. To recap, product usability is not a single measure but a set of measures of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction that are functions of users, their goals, and environments of use, as (partially) illustrated in Figure 1. One might say that any use of product by any user reflects the product usability. Therefore usability is typically a complex measure, especially with product products that have a large user base. It is essential that a usability design model manage the complexity of usability.

- 6. University of Oulu 6 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 measures of usability effectivenes efficiency satisfaction effectivenes efficiency satisfaction effectivenes effectivenes s efficiency satisfaction effectivenes s efficiency satisfaction effectivenes s effectivenes s efficiency satisfaction effectiveness efficiency satisfaction effectivenes s efficiency s task environ s task environ s task characteristi environ task ment task characteristi environment task characteristi task csenvironment characteristi task csenvironment characteristi task characteristi characteristics mentgoal characteristi cs ment goal characteristi cs cs goal cs goal cs goal goal goal user user user Figure 1. Usability is a set of measures that build on users, goals, task characteristics and environments. 4 Overview of the KESSU UD Process Model The basics of the KESSU UD model lies in ISO 13407, which identifies four main user-centred design activities, illustrated in Figure 2. ISO/TR 18529 further explicates the ISO 13407 model to be applicable in process assessment through defining the processes with purpose statements, outcomes and base practices. identify need of human-centred design understand & specify the context of use evaluate designs specify the user & against organizational requirements requirements produce design solutions Figure 2. Activities of user-centred design: ISO 13407 In the KESSU model, the key definition of processes is the outcomes. Outcomes are typically — but not necessarily always — concrete deliverables (e.g., documents) that

- 7. University of Oulu 7 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 should be produced as a result of a usability process. Outcomes are the “what” of usability design; methods and principles are the “how.” We categorize the outcomes around six usability engineering processes, as the model in Figure 3 shows. The usability engineering processes feed user data into the interaction design processes, shown in the centre of the model. We identify seven different usability design processes (instead of four of ISO 13407 and ISO 18529). Six of them are usability engineering processes and one user interaction design process. In summary, we identify the following processes: The UE processes: • IDENTIFICATION OF USER GROUPS • CONTEXT OF USE ANALYS IS • USER REQUIREMENTS DETERMINATION • USER TASKS REDESIGN • USABILITY FEEDBACK • USABILITY VERIFICATION The UID process: • INTERACTION DESIGN The processes and their relationships are informally illustrated in Figure 2. In the Appendix 1: Definitions of processes, each process and the outcomes is defined in further detail. The model has evolved step by step through empirical findings and differs from the ISO 13407 and ISO 18529 models in: • Being systematically method independent • Taking the definition of usability carefully into account • Systematically using outcomes when defining the processes • Deliberately drawing a clear line between design and usability engineering activities

- 8. University of Oulu 8 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Identifica- tion of user User goals groups User Context of use groups Context of use of user group User task of user1group Context of use characteristics 1 of analysis Environments of use business drivers Adherence to design Usability requirements requirements Usability Usability feedback User requirements verification Interaction determination design Design Meeting requirements usability corporate requirements practices Software User task User task Design guidelines descriptions redesign Style guides Figure 3. Visualisation of the KESSU UD process model. Processes are modelled as ellipses, and outcome s as boxes. Unlike many other usability design models, we separate the usability and design processes. The outcomes of these two types of processes are different in nature. Usability processes produce user data, such as user descriptions, usability requirements, and usability evaluations. Design processes produce the actual designs: interaction and visual designs, user interface software, user documentation, and so on. This separation is useful because those who do usability (usability specialists) are typically not the same people as those who produce designs (software and other designers). Moreover, the model illustrates that it is not enough to introduce usability engineering processes only — the existing design processes need to change as well. Usability processes have no value unless the results are taken into account in the design processes. There are two other factors that also affect usability design. First, companies typically have design requirements — restrictions that must be considered when designing the user interface elements. These include style guides, company standards, and/or project standards. Second, business drivers naturally have a major impact on the usability design process. They determine the product business case and set boundaries on the available resources.

- 9. University of Oulu 9 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 5 Using the model in planning usability design Planning and implementing usability design are the responsibilities of usability specialists. The outcomes of the processes, illustrated in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 1, can be used as a basic checklist when discussing and planning usability actions with other stakeholders of a development project. User group definitions User goal definitions Descriptions of user task characteristics Descriptions of environments of use Usability requirements User interface design requirements User task descriptions Qualitative usability findings Quantitative usability measures Table 1. The outcomes as a checklist The process model of Figure 3 suggests the following sequence of usability design activities: • Identify user groups. • Determine user goals for each user group and then user task characteristics and environments of use. • Based on the outcomes of the two first steps and business drivers, determine usability requirements. At the same time, define the design requirements (which style guides to use, which design practices to follow, etc.). • Redesign user tasks. The earlier outcomes — apart from design requirements — are useful inputs to this. • Produce interaction designs: the interaction and visual designs, user documentation, package design, and so forth. • Qualitatively evaluate the interaction design proposals, and provide feedback to the interaction design process. • Quantitatively evaluated against usability requirements. This is the logical order, and it can be used to guide the planning of a usability process. In practice, however, iteration takes place not only between design and usability evaluation but in the earlier phases as well. For example, when working with user goals, the project team often realizes that the first definition of user groups was not the right. It is advisable to plan the usability design process so that each type of outcome is produced at least partly. The usability activities and outcomes form a logical

- 10. University of Oulu 10 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 continuum: if one type of outcome is not produced, then there is a hole in the usability design lifecycle. The early phases of the process — from user group definitions to usability and design requirements — are important; they are about determining what makes the product usable. It is possible to do usability testing and other evaluations without a proper definition phase. However, without the outputs from the requirements phase, such evaluations have a weak foundation. 5.1 Mapping usability methods with the model Methods are the practical — and necessary — means for producing the outcomes. Depending on the situation, the project team may choose simple methods or more elaborate ones. When selecting simple methods, the team should understand that the quality of the outcomes may not be as good as with advanced methods. However, even a sophisticated guess is better than nothing. A basic usability method for the early phases is the stakeholder meeting. A stakeholder meeting is a facilitated workshop involving the members of the project team and other stakeholders — which may or may not include users. Stakeholder meetings can be used to generate the outcomes of the early phases in an efficient and inexpensive way. Valid user data may be produced even without immediate user participation, provided the participants have grounded knowledge about users (i.e., participants have been in contact with users in different situations, such as customer service). If, on the other hand, participants in a stakeholder meeting discover that they need further user involvement to produce valid outcomes, they will need to employ more elaborate methods. In the early phases, true user involvement may come through methods such as user surveys, user interviews, and user observations (contextual inquiry). These results are typically processed in subsequent stakeholder meetings. Typical user task redesign methods are storyboarding or scenario writing. The most effective way of evaluating usability is usability testing, but various expert evaluations may be carried out as well. Table 2 maps the outcomes with possible methods for achieving them. In this context, prototyping as such is not considered a basic usability method. Prototypes are supporting technical solutions for making design solutions “real” quickly. Therefore, prototypes have a critical role, although they are not formally methods. 5.2 How much to do? It is not feasible to do complete usability design. On the one hand, there always are limitations on how many resources can be used. On the other hand, the complex nature of usability (see discussion in section 3) also sets practical limitations. Even the requirements phase is typically too complex to be implemented completely.

- 11. University of Oulu 11 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Outcome Sample methods User group definitions Stakeholder meeting Interviews User surveys User goal definitions Stakeholder meeting Contextual inquiry Personas Descriptions of user task Stakeholder meeting characteristics Contextual inquiry Descriptions of environments Stakeholder meeting of use Contextual inquiry Personas Usability requirements Stakeholder meeting Consolidation User interface design Stakeholder meeting requirements User task descriptions Storyboarding Scenario writing Evaluation of design Usability testing Expert evaluations Inspection Table 2. Sample usability methods for producing outcomes Be that as it may, it is still better to use even very rough and ad hoc methods than not to produce the outcomes at all. It may later prove that the outcomes were not totally the right ones: some relevant user group was not analysed, or usability requirements were unrealistic. However, making things explicit is helpful, and generating the outcomes is a useful thinking process. If something goes wrong, the team can at least identify where the problem was and improve next time. Some systems, especially off-the shelf products for international markets, necessarily have a great variety of different users. In such cases, the project team may find it reasonable to exclude minor user groups from detailed analysis or not pay attention to different environments of use. However, the team should make these kinds of decisions explicitly. 5.3 If Usability Requirements Are Not Met What if usability requirements are not met by the end of the lifecycle? Should the team perform repeat iterations until the requirements are met? If a particular usability requirement is merely a “nice to have” feature, it may be easy to let it slip from the iteration if it appears the project team will have difficulty meeting the requirement. The situation is totally different if the usability requirement has some true value to the customer. Iteration would probably take place if the

- 12. University of Oulu 12 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 usability requirements are stated in the contract and the customer strictly demands that they be achieved. This, however, is probably still rather seldom the case. One way to establish the value of usability requirements is to couple project incentives with the achievement of the usability requirements. Our experience shows that the extra salary that project staff gets from achieving usability targets truly motivates them to work toward better usability. 5.4 Bridging the Gap Between Usability design and Product Design In practice, usability engineers and designers are not the same people. The role of the usability specialists is to provide usability drivers, requirements, and guidance to designers and evaluate the design proposals, as illustrated in Figure 3. It is important to understand that, in the end, the usability of a product is not built into the product by usability engineers but by those who design the product — software and other designers. Carrying out usability design actions, even using advanced methods, is not adequate for making product usable if the results do not have an impact on the design solutions. It is not easy for usability engineers to influence the way designers do designs. Probably the most effective means for bridging the gap between usability and design is cross- functional teamwork. The stakeholder meetings are an example of effective teamwork that enables designers and usability practitioners to work through usability issues. The good news is that designers usually take to usability on contact; in our experience, the outcomes and processes of usability design seem to make sense to designers once they learn about them. The challenge lies in motivating designers to participate in the teamwork in the first place. 5.5 Integration with the Product Development Lifecycle How does usability design integrate with the product development lifecycle? The basic rule is do usability actions early in a product project. Usability requirements may affect even the architecture of the product, so the project team should carry out the usability activities during the requirements phase whenever possible. Fortunately, the usability design lifecycle does not require any new software. Effective techniques — such as paper prototyping [17] — make it feasible to evaluate the usability of a future product without a single line of code. 5.5.1 Managing the Usability design Process To check the status of usability actions in a development project, first examine the extent to which the various outcomes are produced. This assessment should provide an overall picture of the status of usability actions on the project, even to persons who are not usability professionals. The project team can then examine the status at a more detailed level. The main questions are: How do we know that the outcomes are right? How do we know that designers have considered usability results in the design solutions? To get valid answers to these questions, the help of an experienced usability specialist is required. Expertise is needed for understanding whether appropriate methods are used in a

- 13. University of Oulu 13 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 professional way. This individual can also judge whether the usability actions truly have had an impact on design solutions. 6 Using the model in the assessment of user-centred design In an assessment, the performance of the usability design processes is assessed through examining the outcomes of the processes with performance attributes. We identify three performance attributes: • The quantity of an outcome. The more extensively an outcome is produced, the higher rating it gets. • The quality of an outcome. With this dimension, the quality and validity of the outcomes is examined. • The integration of an outcome. The more extensively an outcome has impact on the design and on other usability processes, the higher rating is given to integration attribute. The basic attribute is ‘quantity’. It determines to which extent an outcome is produced. The more extensively the outcome is produced, the higher rating is given. Examination of the ‘quantity’ dimension is the basic thing. The examination of other dimensions is meaningful only if an outcome is produced at least partially. The rating of the ‘quality’ dimension is determined based on the validity of the methods and professionalism. The more appropriate usability methods are used and the more professionally they are implemented, the higher rating is given. The experience of many usability practitioners is that the results of their work are not considered in the design decisions. The ‘integration’ attribute examines this viewpoint. The more impact the results of an outcome have on design, the higher rating is given. We use the performance of attributes with a 4- level scale which used in the rating of base practices of formal process assessment. They are described in further detail in Appendix 2: Performance attributes. We emphasize that the examination of a development process through outcomes does not necessarily mean that the outcomes should not be documents. Usability engineering activities basically could be implicit: e.g. the stakeholders could share the same understanding on who are the different user groups of the end product. However, it is no t very believable that all the outcomes of usability engineering would exist but not documented. For example, if measurable usability goals (one intermediate outcome of usability engineering) are produced, they most probably would be documented. Further discussion and experiences on the assessment of usability design can be found in [14].

- 14. University of Oulu 14 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 7 Discussion Usability engineering should have a firm basis and not be driven by usability methods that are more or less unstable. This document proposes the KESSU model of usability design that is defined independent of methods, through processes and outcomes. Our empirical findings – in assessments, in trainings and design workshops – indicate that this kind of definition of processes (through concrete outcomes, clear limitation of the scope of processes) has worked and communicated well. The KESSU model does not make explicit the iterative and cross- functional nature of the UD work: the model does not explicitly require iteration and cross-functional teamwork to take place. These aspects, as well as true user involvement, are implicitly in the quality attribute. The production of high quality outcomes typically requires user involvement, iteration and cross- functional teamwork. Integration of outcomes typically requires cross- functional work, too. This document mainly discusses process issues. However, if there is one thing that management should pay special attention to, it is probably the challenging organizational position of usability specialists. Their job of bridging the gap between usability and software design is not an easy one — as the not-so-small number of frustrated usability practitioners indicates. This is an area where managerial support may well be required. 7.1 Limitations There have been two earlier major versions of the model. The model has evolved when more experience is gained. Our understanding is that the model will be refined with further experience. The interpretation of the processes is based on my personal understanding of designing usability. It is very possible that some others will disagree with my interpretation. Writing ‘good’ documentation of a model is a challenging task. I have personally found challenging the interpretation of even well documented models of other authors. I am sure that the readers of this document may find many interpretation problems. Please do not hesitate to contact the author (timo.jokela@oulu.fi). 7.2 Implications for Practitioners This process model was developed for the purpose of assessments of user-centred processes. Its main application for practitioners, however, could be – as it actually has been - a general framework of UD in training of and a high- level guide in the practical implementation of UD. The process model defines the outcomes that should be generated. It discusses only at a general level the practical methods for how to produce those outcomes. Issues such as the skills that a practitioner should have to carry out UD work are not discussed at all.

- 15. University of Oulu 15 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 It is not practical and not even recommendable to aim for producing all the outcomes fully in regard with all the performance attributes. In practice, there is no ideal UD. Rather, one should try to understand which processes and outcomes to fo cus, in order to make the UD as effective as possible in the context a development project. One general advice, however, could be given: try to generate all the outcomes – especially also the ones in the early phases, at least to some extent. References 1. Jokela, T., N. Iivari, M. Nieminen, and K. Nevakivi. Developing A Usability Capability Assessment Approach through Experiments in Industrial Settings. in Joint Proceedings of HCI 2001 and IHM 2001. 2001: Springer, London. 2. Jokela, T. An Assessment Approach for User-Centred Design Processes. in Proceedings of EuroSPI 2001. 2001. Limerick: Limerick Institute of Technology Press. 3. Jokela, T., Assessment of user-centred design processes as a basis for improvement action. An experimental study in industrial settings. Acta Universitatis Ouluensis, ed. J. Jokisaari. 2001, Oulu: Oulu University Press. 168. 4. Jokela, T. A Method-Independent Process Model of User-Centred Design. in IFIP 17th World Computer Conference 2002 - TC 13 Stream on Usability: Gaining a Competitive Edge. 2002. Montreal: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 5. Jokela, T. Making User-Centred Design Common Sense: Striving for an Unambiguous and Communicative UCD Process Model. in NordiCHI 2002. 2002. Aarhus, Denmark: ACM. 6. Jokela, T. Assessment of User-Centred Design Processes - Lessons Learnt and Conclusions. in Proceedings of Profes 2002. 2002. Rovaniemi, Finland. 7. Jokela, T. Assessments of Usability Engineering Processes: Experiences from Experiments. in HICSS -36. 2003. Hawaii. 8. Jokela, T., Beyond Usability Methods: Usability Engineering Through Processes and Outcomes. Cutter IT Journal, 2003. 16(10): p. 13-20. 9. Jokela, T., Evaluating the user-centredness of development organisations: Conclusions and implications from empirical usability capability maturity assessments. Interacting with Computers. In press, corrected proof, 2004. 10. ISO/IEC, 13407 Human-Centred Design Processes for Interactive Systems. 1999: ISO/IEC 13407: 1999 (E). 11. ISO/IEC, 18529 Human-centred Lifecycle Process Descriptions. 2000: ISO/IEC TR 18529: 2000 (E). 12. Beyer, H. and K. Holtzblatt, Contextual Design: Defining Customer-Centered Systems. 1998, San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. 472. 13. Mayhew, D.J., The Usability Engineering Lifecycle. 1999, San Fancisco: Morgan Kaufman. 14. Jokela, T., Evaluating the user-centredness of development organisations: conclusions and implications from empirical usability capability maturity assessments. Interacting with Computers (Article in Press, Corrected Proof), 2004.

- 16. University of Oulu 16 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 15. ISO/IEC, 9241-11 Ergonomic requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDT)s - Part 11 Guidance on usability. 1998: ISO/IEC 9241-11: 1998 (E). 16. ANSI, Common Industry Format for Usability Test Reports.. 2001: NCITS 354-2001. 17. Snyder, C., Paper Prototyping. The Fast and Easy Way to Design and Refine User Interfaces. 2003, San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

- 17. University of Oulu 17 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Appendix 1: Definitions of processes The process defintions have the following structure: • Purpose: a brief definition of why the process exists. • Description: an informal characterisation of the process • Outcomes: what outcomes (typically concrete deliverables) a process should produce. In the definitions – especially in the purpose statements - we partially use the wordings used in ISO 18529. We identify the outcomes of the processes but not the inputs (as typically are done in process descriptions). The main reason for this is to keep the model simple. If we included all the inputs, the model would become complex while the (1) many processes have many inputs and (2) the iterative nature of the UD process would make the model even more complex. Identification of users groups Purpose The purpose of the process Identification of user groups is to identify and categorise the different user segments: who are potential users of the product or system. In this document, we do not suggest any specific strategy for categorisation. The categorisation, however, needs to be meaningful and provide a good basis for the subsequent processes. Description The substance of this process is not explicitely included in ISO 13407 or ISO/TR 18529. We, however, find it sensible to be explicitely included in the model. Outcomes As a result of successful implementation of this process the f llowing outcomes are o achieved: User groups definitions The various user groups of the product should be identified. The relevant characteristics of each user group should be described. These may include job descriptions, knowledge, language, physical capabilities, anthropometrics, psychosocial issues, motivation for using the system, priorities, etc. An identifiable name should be given to each user group and the importance of each group (e.g. on the basis on how many users belong to this group) should be determined. Context of use analysis NOTE. This process needs to have an instance for each user group identified by the previous process.

- 18. University of Oulu 18 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Purpose The purpose of the Context of use analysis process is to establish and communicate the goals of users, characterise the tasks of users, the technical, organisational and the physical environment – as relevant - in which the product system will operate. Description The nature of this process is 'data elicitation and analysis'. It produces information about users, their goals and tasks, problems in performing tasks etc. On the other hand, this process is not a decision making process. The User requirements process makes conclusions based on the CoU information for the goals and requirements of the systems. Outcomes As a result of successful implementation of this process the following outcomes are achieved: User goals User goals (‘accomplishments’) should be determined in terms of what users need to accomplish with the product, not in terms of the equipment, functions or features of the software. It is important to understand that the user goal is a result, not a name or description of a task. Tasks characteristics Users achieve the goals through tasks. The characteristics of the tasks describe the nature of the tasks, for example frequency, duration of performance, criticality for errors, and whether the tasks are carried out under pressure or in a stressful situation. Environment of use The operational environment where the product is used should be regarded as relevant. Environment descriptions may include technical, physical and social factors. User Requirements Determination Purpose The purpose of this process is to define usability and UI design requirements for the product under development. The outcomes of this process should drive decision- making in the design processes. Description The main input for this process is the context of use information and business goals of the project. While business goals should drive the all usability processes, they especially should drive the User requirements process. One should understand that usability requirements might contradict with other requirements. Resolution between conflicting requirements should be performed in this process.

- 19. University of Oulu 19 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Outcomes As a result of successful implementation of this process the following outcomes are achieved: Usability Requirements Usability requirements are the required performance of the product from the user task performance point of view. Usability requirements could be given in terms of effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a quantitative way, as defined in [15]. UI Design Requirements Whereas usability requirements give the drivers for the design, design requirements set the restrictions that should be considered when the user interface elements are designed. Typically these include style guides and company or project standards. User Task Redesign Purpose The purpose of this process is to design how users are to carry out their tasks with the new product that is being developed. Description This is design phase where ‘the work of the users’ is designed: what are the accomplishments that there product will give support, and what are the scenarios of steps for how these accomplishments are reached. This phase is not yet design of user interface elements. Outcomes As a result of successful implementation of this process the following outcomes are achieved: User task descriptions In this process, the design should comply with how users are to carry out the tasks to achieve their goals with the new product being developed. It is essential to understand that better usability means better work practices. This design process produces a set of descriptions of the improved work practice of the users: i.e. how the user will carry out the tasks with the new product. Usability Feedback Purpose The purpose of this process is to qualitatively evaluate the product (including user documentation, user training etc.). Description This process is typically highly iterative with the Interaction Design process. Typical methdos for this process are qualitative usability tests and various usability inspections.

- 20. University of Oulu 20 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Outcomes Usability feedback Usability feedback is qualitative feedback on the usability of the design proposal. This outcome is typically an iterative set of evaluation results which identify those parts of the design solutions that work, and those which should be improved. Usability Verification Purpose The purpose of this process is to measure the product under development (including user documentation, user training etc.) against the usability and design requirements. Description This process addresses on usability only from the task performance aspect. Those activities that evaluate the generic, non-task driven issues (for example, heuristic evaluations, or adherence to style guides etc.) are activities of the Produce user interaction designs process. Outcomes Verification results against usability requirements The product is evaluated in order to determine to what extent the product meets the defined usability requirements and a report of the adherence is produced. Verification results against design requirements The design solutions of the user interface are checked against the design requirements and a report of the adherence is produced. Interaction Design There can be identified a number of design processes. The design processes, however, are not discussed in detail in the context of this document. Therefore, we depict the design activities through one process only. Purpose The purpose of this process is to design those elements of the product that are users interact with. These elements include interaction and graphical design of user interface, user documentation, user training, user support, etc. Description This process is different in one essential respect compared with the other processes of this category: a full output of the process is typically produced even if there were no user-centredness in the project. Another specific feature of this process is that the different outcomes should be produced parallel. People from different departments (user interface development, user documentation, customer training) typically work together.

- 21. University of Oulu 21 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Outputs As a result of successful implementation of this process the following outcomes are achieved: User interface The user interface (interactions, visual design) is produced. User documentation The user documentation is produced. User training The user training material and concepts are produced. Other relevant outputs Other relevant outputs are generated, for example packaging, user support procedures etc.

- 22. University of Oulu 22 Prepared File Version TIMO JOKELA KESSU UD Process Model 2.1.doc 2.1 Appendix 2: Performance attributes In an assessment, the performance of the usability design processes is assessed through examining the outcomes of the processes with performance attributes: • The quantity of an outcome. The more extensively an outcome is produced, the higher rating it gets. • The quality of an outcome. With this dimension, the quality and validity of the outcomes is examined. • The integration of an outcome. The more extensively an outcome has impact on the design and on other usability processes, the higher rating is given to integration attribute. The achievement of the performance attribute is rated with a 4-level scale, taken from the rating practice of base practices of formal process assessment: Rating Numerical Description equivalence N Not achieved 0 There is no or only very marginal evidence of the achievement of the defined dimension P Partially achieved 1 There is some relevant achievement of the defined dimension L Largely achieved 2 There is significant achievement of the defined dimension. F Fully achieved 3 There is full achievement of the defined dimension.