Oklahoma's Native Vegetation Types

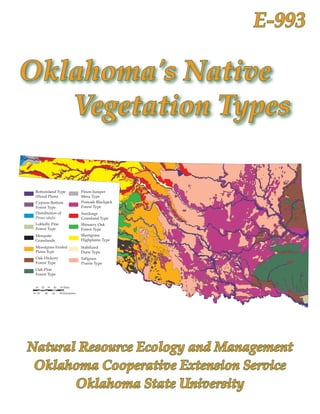

- 1. E- Oklahoma's Native Vegetation Types Bottomland Type Pinon-Juniper (Flood Plain) Mesa Type Cypress Bottom Postoak-Blackjack Forest Type Forest Type Distribution of Sandsage Pinus edulis Grassland Type Loblolly Pine Shinnery Oak Forest Type Forest Type Mesquite Shortgrass Grasslands Highplains Type Mixedgrass Eroded Stabilized Plains Type Dune Type Oak-Hickory Tallgrass Forest Type Prairie Type Oak-Pine Forest Type 10 20 30 40 50 Miles 10 20 40 60 80 Kilometers Natural Resource Ecology and Management Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service Oklahoma State University

- 2. Oklahoma's Native Vegetative Types Ronald J. Tyrl Professor of Botany Department of Botany, Oklahoma State University Terrence G. Bidwell Professor and Extension Rangeland Specialist Department of Natural Resources Ecology and Management Oklahoma State University Ronald E. Masters Director of Research Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida R. Dwayne Elmore Assistant Professor and Extension Wildlife Specialist Department of Natural Resources Ecology and Management Oklahoma State University John R. Weir Research Associate Department of Natural Resources Ecology and Management Oklahoma State University

- 3. Oklahoma State University, in compliance with Title VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive Order 11246 as amended, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and other federal laws and regulations, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, age, religion, disability, or status as a veteran in any of its policies, practices, or procedures. This includes but is not limited to admissions, employment, financial aid, and educational services. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Robert E. Whitson, Director of Cooperative Extension Service, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma. This publication is printed and issued by Oklahoma State University as authorized by the Vice President, Dean, and Director of the Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources and has been prepared and distributed at a cost of $1,911.15 for 750 copy. 0907 JA

- 4. ECOGEOGRAPHY OF OKLAHOMA B otanically, Oklahoma is a remarkable state! Within its borders, 173 fami- lies, 850 genera, and 2,465 species of vascular The distribution of Oklahoma’s vegetation types generally reflects these two gradients, with deciduous forests in the eastern third of the state plants can be found. Located at the juncture of giving way to tallgrass and mixedgrass prairie in several physiographic provinces, it is an eco- the middle and shortgrass prairie in the west. logical crossroad. Plants representative of sev- Temperature in Oklahoma also exhibits sea eral phytogeographic regions are present, with sonal and geographical variation, although not species characteristic of the eastern deciduous as strikingly as precipitation. In the eastern part forests and grasslands being most common. The of the state, temperature averages are lower in diversity of plant vegetation types present—14 the summer and higher in the winter. The frost- are traditionally recognized (Duck and Fletcher free season averages 225 days in the south to map on the cover)—reflects this diversity of less than 170 days in the north (Figure 1c). As is species. characteristic of a continental climate and famil- This tremendous diversity of plant species iar to all who live in the state, daily temperature and communities in Oklahoma reflects the con- fluctuations can be abrupt and dramatic. As siderable variation in the state’s climatic, phys- might be expected, species richness—the number iographic, geological, and edaphic features. A of different species present in an area—is greatest plethora of different habitats for plants is present. in the southeast corner of the state, which has Brief descriptions of this variation are presented the mildest winter temperatures and the longest in the following paragraphs. growing season. Climate Oklahoma’s continental climate is character Physiography and Geology ized by geographical and seasonal variability in In addition to being botanically diverse, Okla both precipitation and temperature (Oklahoma homa also is physiographically and geologically Climatological Survey, 1990). The eastern part of varied and complex (Johnson et al., 1979). Strata the state is more strongly influenced by moisture from every geological time period can be found from the Gulf of Mexico than the drier western exposed at one point or another within the state’s portion of the state. Average yearly precipitation boundaries (Figure 2). Approximately 99% of the varies from more than 56 inches (1,400 mm) in formations are sedimentary; e.g., the familiar the southeast to less than 16 inches (400 mm) in Permian sandstones in the west, the Mississip- the extreme northwest—a gradient of about 1 pian limestones in the northeast, and the Ordo- inch (25 mm) of rainfall for every 15 miles (25 vician to Pennsylvanian sandstones and shales km) traveled from east to west (Figure 1a). in the southeast. The remaining 1% is igneous Likewise, the Precipitation Effectiveness In (Wichita Mountains) or slightly metamorphic dex—the ratio of precipitation to evaporation in (parts of the Ouachita Mountains). 24 hours and an index of the growing conditions One of the common misconceptions about faced by plants—exhibits a gradient across the Oklahoma is that it is monotonously flat, with little state; more than 65% in the east to less than 25% topographic variation in its landscape. In reality, in the west (Figure 1b). this is not the case. Only a few areas of the state are

- 5. truly flat. Rolling hills and broad plains dissected tisols dominate in the eastern third of the state; by broad river valleys are more characteristic. The alfisols and mollisols in the center, and inceptisols Ozark Plateau and three mountain provinces— in the western third. Covering more area of the Ouachita, Arbuckle, and Wichita—provide con- state than any of the other soil types, the dark, spicuous relief. In addition, escarpments, cuestas, rich mollisols also are characteristic of the state’s buttes, mesas, narrow canyons, and deep ravines northeastern prairie and central Panhandle areas. are present. Twenty-six geomorphic provinces— Also present are vertisols and entisols. large regions of similar landforms resulting from A mosaic of clay, loam, and sandy soils occurs erosion and/or deposition of sediments—have across the state’s landscape. The physical prop been described in Oklahoma (Figure 3). The varied erties of these soils; for example depth, water, topographic features of these provinces provide a nutrient holding capacity, aeration, and resis- diversity of habitats for plants. tance to erosion, markedly influence the plants growing in them, and often distinctive, easily Soils observed assemblages of species will character- As might be expected because of Oklahoma’s ize them. Illustrative of this relationship is the geological and physiographical diversity, its soils sandsage-grassland community associated with also are quite diverse (Figure 4). In general, ul the sandy soils of western Oklahoma. Figure 1. Climatic features of Oklahoma. (a) average annual precipitation (inches; Oklahoma Climatological Survey, 1997).

- 6. Figure 1. (continued) (b-top) normal precipitation effectiveness (%; adapted from Curry, 1970). (c-bottom) length of grow- ing season (days; Oklahoma Climatological Survey, 1997).

- 7. Figure 2. Generalized geologic map of Oklahoma (adapted from Branson and Johnson, 1972).

- 8. Figure 3. Geomorphic provinces of Oklahoma (adapted from Curtis and Ham, 1972).

- 9. Figure 4. General Soil Map of Oklahoma (Carter, 1996).

- 10. VEGETATION OF OKLAHOMA correlated with prior studies of vegetation, O klahoma has 173 families, 850 genera, and 2,465 species of vascular plants. Within its borders, Oklahoma has plants characteristic of geology, soils, climate, and land use in relation to game animal populations. In the decades since the publication of Duck and Fletcher’s map, the forests of New England, the swamps of the vegetation studies in the state focused only on Gulf Coast states, the deserts of the Southwest, distinctive, local ecological areas or tracts of par- the mountains of the West, and the prairies of ticular economic or conservation interest. A mod- Canada. Fourteen vegetation types are tradition- ern classification of the state’s vegetation was not ally recognized and they reflect this diversity. attempted until the late 1990s when Hoagland These vegetation types and their alteration by (2000) published a scheme based on guidelines human activity are described in the following developed by the Vegetation Subcommittee for paragraphs. Classification and Information Standards (FGDC, 1997). He recognized 121 alliances in 151 associa- History of Classification tions. This detailed classification, incorporating Descriptions of the flora and vegetation of all previous systems, provides scientists with a Oklahoma begin with the observations of early basis for landscape mapping and conservation visitors such as Vasquez de Coronado, Juan de planning. Onate, Thomas Nuttall, Edwin James with the Long expedition, Washington Irving, Charles Synopsis of Vegetation Types Lathrobe, Josiah Gregg, S.W. Woodhouse with In this publication, we continue to use the the Sitgreaves and Woodruff expedition, G.G. Duck and Fletcher system because it is easy to use Shumard with the Marcy expedition, and J.M. by individuals with diverse backgrounds. Brief Bigelow with the Whipple expedition (Bruner, descriptions of the 14 categories recognized by 1931; Featherly, 1943). In their journals and expe- them are presented in the following paragraphs. dition reports are glimpses of the state’s vegeta- It must be noted that although Duck and Fletcher tion prior to the arrival of eastern tribes of Native mapped the distribution of pinion pine, Pinus Americans and Europeans. edulis (light blue on map), they did not describe it Systematic description of the vegetation, how as a distinct type in their 1945 treatise, but rather ever, is traditionally considered to begin with the included it in their Pinon-Juniper Mesa type. work of W.E. Bruner (1931) and W.F. Blair and T.H. Hubbell (1938). Their seminal monographs Forest Types were followed by publication of L.G. Duck and Oak-Hickory J.B. Fletcher’s vegetation map (1943, 1945), which In Oklahoma, this type represents the western serves as the cover graphic of this publication. edge of the eastern deciduous forest, with spe- The most widely recognized of all Oklahoma cies characteristic of the Ozark Plateau and espe classifications, it comprises 14 vegetation types cially the northeast quarter of the continent. Its called “game types” because the authors’ intent distribution coincides primarily with the limits was to describe habitats of game and fur-bearing of the Ozark Plateau Physiographic Province. animals in the state. The classification, descrip- Taxa typically encountered include: black oak, tions, and map are the product of field mapping

- 11. Quercus velutina; white oak, Q. alba; northern red bald cypress, Taxodium distichum; sweetgum, L. oak, Q. rubra; post oak, Q. stellata; mockernut styraciflua; blackgum, N. sylvatica; water oak, Q. hickory, Carya tomentosa; and bitternut hickory, C. nigra; willow oak, Q. phellos; and other woody cordiformis. Pockets of shortleaf pine, P. echinata, and herbaceous species characteristic of the also are present. Numerous other tree, shrub, and southeast quarter of the continent. herbaceous species characteristic of the decidu ous forest likewise occur. Bottomland (Flood Plain) Associated with gravel and sand bars, and the Oak-Pine lowest terrace of all river and creek systems, this This type is similar to the Oak-Hickory forest, type occurs across the state and is quite variable but includes short leaf pine, P. echinata, in abun- with respect to the species present. In the west, dance and other species characteristic of the south- cottonwood, Populus deltoides; species of willow, east quarter of the continent. Some ecologists do Salix; and the introduced salt cedar, Tamarix chi- not recognize it as a distinct type. Its distribution nensis, are encountered. In the east, sycamore, coincides with the limits of the Ouachita Mountain Platanus occidentalis; green ash, Fraxinus pennsyl- Province. In addition to the species characterizing vanica; white ash, F. americana; American elm, U. the Oak-Hickory Forest, also encountered are americana; and species of hackberry, Celtis spp., blackjack oak, Q. marilandica; winged elm, Ulmus also occur. Herbs, vines, and shrubs are typically alata; water oak, Q. nigra; willow oak, Q. phellos; abundant in the understory. and blackgum, Nyssa sylvatica. Grassland Types Post Oak-Blackjack Oak Tallgrass Prairie As its name implies, this type is dominated Covering the greatest area of Oklahoma, this by post oak, Q. stellata, and blackjack oak, Q. type dominates the center of Oklahoma from north marilandica, the two most abundant tree species to south. In some areas, the Post Oak-Blackjack in Oklahoma. Distributed in a north-south swath Oak Type bisects the Tallgrass Prairie and typically across the state, it typically forms a mosaic with forms the mosaic collectively referred to as the the Tallgrass Prairie, the two types being col- “Cross Timbers.” Often reaching heights of 3.28 lectively referred to as the “Cross Timbers.” As- sociated species include black hickory, C. texana; to 9.84 feet (1 to 3 m), big bluestem, Andropogon Shumard’s oak, Q. shumardii; chittamwood, gerardii; little bluestem, Schizachyrium scoparium; Bumelia lanuginosa; sugarberry, Celtis laevigata; Indiangrass, Sorghastrum nutans; and switchgrass, and northern hackberry, C. occidentalis. In several Panicum virgatum, dominate. Numerous other areas along its eastern edge, it is contiguous with perennial grasses and forbs are present. the oak-hickory and oak-pine forests. Shortgrass Prairie – High Plains Loblolly Pine Occurring in the counties of the Panhandle Also a portion of the eastern deciduous for and the extreme northwest corner of the body of ests, this type is dominated by loblolly pine, the state, this type is dominated by shortgrasses P. taeda, and other species characteristic of the such as buffalograss, Buchloe dactyloides, and blue southeast quarter of the continent; e.g., southern grama, Bouteloua gracilis. In moister sites, sideoats red oak, Q. falcata, and sweetgum, Liquidambar grama, Bouteloua curtipendula, and little bluestem, styraciflua. Its distribution corresponds to the S. scoparium, are present. Characterized by low, ir level, sandy soils of the Dissected Coastal Plain regular precipitation, these grasslands are nearly Geomorphic Province. devoid of trees. Cypress Bottoms Mixedgrass – Eroded Plains Present only in the drainages of the Little and Distributed across the western quarter of the Mountain Fork rivers, this type is dominated by body of the state, this type comprises a mixture

- 12. of tall- and shortgrasses. The more mesic eastern Oklahoma. As its name implies, stabilized sand tallgrasses occur where conditions are moist, dunes are its predominant topographic feature. whereas the western shortgrasses occur in the Sand-loving species playing important roles drier habitats. Trees and shrubs, such as eastern in stabilization and succession include: giant redcedar, Juniperus virginiana, and hackberry, sandreed, Calamovilfa gigantea; sand bluestem, Celtis spp., occur in deeply eroded ravines and A. gerardii ssp. hallii; lemon sumac, R. aromatica; canyons. sand plum, P. angustifolia; soapberry, Sapindus drummondii; and chittamwood, B. lanuginosa. Shrub – Grassland Types Sandsage Grassland Pinon-Juniper Mesa This type is defined to encompass all sandy In extreme northwest Cimarron County, Black grasslands in which sandsage, Artemisia filifolia, Mesa and the surrounding area support isolated stands of species characteristic of the western half is an important part of the cover. Distributed of the continent, including pinon pine, P. edulis; primarily throughout the northwest corner of one-seeded juniper, J. monosperma; and ponderosa the state, including the Panhandle, it occurs pine, P. ponderosa. Associated with these woody mainly on the north sides of the principal rivers species are shortgrass and herbaceous species and creeks. Species characteristic of sandy soils typical of the xeric conditions present. dominate and include sand bluestem, A. gerardii ssp. hallii; sand plum, Prunus angustifolia; lemon Vegetation Types and Ecogeography sumac, Rhus aromatica; sand lovegrass, Eragrostis As one traverses Oklahoma, it quickly be trichodes; and plains yucca, Yucca glauca. comes obvious that the distribution of the state’s vegetation types is correlated with climatic and Mesquite Grassland edaphic gradients, and their geographical dis- Occurring in the southwest corner of the tribution is somewhat predictable. This general state, this type comprises shortgrass species relationship is summarized in Figure 5. Histori- such as buffalograss, B. dactyloides; blue grama, cally, overlaying this interaction of soil, precipi- B. gracilis; and sideoats grama, B. curtipendula, as- tation, and vegetation were frequent wildfires, sociated with scattered trees of mesquite, Prosopis herbivory, and droughts. However, the distri- glandulosa. The soils for the most part are clays, butions of some woody species, most notably with gypsum often present. Redberry juniper, J. eastern red cedar, J. virginiana, and mesquite, P. pinchotii; plains yucca, Y. glauca; and plains prick- glandulosa, do not exhibit this relationship. lypear, Opuntia macrorhiza, also are present. Alteration by Humans Shinnery Oak – Grassland Although we have summarized the putative Distributed in sandy soils of the western most “natural” vegetation types of Oklahoma as de counties of the body of the state, this type is the scribed by Duck and Fletcher, it must be stressed eastern edge of a vegetation type that occurs in that these types have been altered significantly by the Texas Panhandle and eastern New Mexico. human activity. The arrival of prehistoric Native The dominant shrub is shinnery oak, Q. havardii, Americans, the relocation of Native American which forms extensive thickets of plants 1.64 to tribes from elsewhere in the country beginning 3.28 feet (0.5 to 1 m) tall interspersed with islands in the 1830s, and the subsequent influx of Euro of taller trees called mottes. Associated species pean settlers in vast numbers in the late 1800s are those characteristic of sandy soils and the impacted Oklahoma’s vegetation. Today, almost Sandsage Grassland type. all vegetation types have been altered to vary ing degrees. Factors contributing to this change Stabilized Dune include suppression of wildfires, plowing of the This type occurs on the north sides of the Ci land, poor management of grazing by domes marron and North Canadian rivers in northwest ticated animals, introduction of invasive exotic plant species, and urbanization.

- 13. 10 Climate Semiarid Humid TexturedTextured Coarse Fine shrubland upland forest forest S shortgrass mixed-grass tallgrass oils prairie prairie prairie Figure 5. Distribution of vegetation types in relation to climate and soils, excluding bottomland forest. Illustrative of this alteration in the landscape periods of time, and then did not occur for five of Oklahoma is the change in the oak-hickory and to twelve years. Such a fire regime reflects the oak-pine forests of the eastern third of the state. occurrence of the early Native American tribes in The arrival of aboriginal peoples in Oklahoma the areas and weather patterns (Foti and Glenn, coincided with glacial retreat in North America. 1991; Masters et al., 1995). Subsequent decline in At that time the eastern portion of the state fire frequency has been correlated with a decline was dominated by boreal forest as indicated by in the population of Native Americans inhabiting analyses of pollen cores (Delcourt and Delcourt, the area, possibly due to the introduction of dis 1987 and 1991). As this boreal forest retreated ease by Europeans and conflicts among different northward, prehistoric peoples used fire as a tool tribes (Gibson, 1965; Wyckoff and Fisher, 1985). to manipulate the forest (Buckner, 1989; Foti and Following relocation of the Choctaw Nation in Glenn, 1991). Plant communities developed under southeastern Oklahoma, fire frequency again the influence of frequent fire coupled with the increased. The region’s fire regime was further ongoing changes in climatic conditions associated altered as Europeans began to settle and actively with the glacial retreat. When Hernando de Soto suppress wildfires (Masters et al., 1995). journeyed into the Ozark region of Arkansas and Likewise, changes in the appearance of the post Missouri in the 1500s, his chronicler described a oak-blackjack oak forests of the Oklahoma Cross land dominated by prairies with trees restricted Timbers are due to the suppression of fire coupled to the drainages (Beilmann and Brenner, 1951). with poor grazing management (Francaviglia, In the 1700s and 1800s, explorers visiting the 2000). The original character of the Cross Timbers Ouachita Mountains described the landscape as was probably a mosaic of grasslands, savanna-like comprising forests or scattered trees interspersed grasslands, oak mottes, oak thickets, and dense with prairies (Lewis, 1924; Nuttall, 1980). oak woods. Grimm (1984) called this spatial Today, closed-canopy forests cover both variation a “fire probability pattern.” It resulted regions. In contrast to the savannah or open from hot, frequent fires sweeping a landscape that woodland structure of the past, these forests have contained both fire-prone topographic sites and overlapping crowns that prevent the growth of natural barriers to fire. Exclusion of fire allowed shade-intolerant herbaceous and woody plants in the development of closed tree canopies, reduced the understory. Suppression of fire is the reason the likelihood of fuel accumulations necessary to for this change. Historically, frequent anthropo support intense burns, and permitted invasion of genic- and (to a lesser extent) lightning-caused woody species such as eastern redcedar into the fires maintained the open nature of the vegetation grasslands, shrublands, and forests. (Masters et al., 1995). Although with an average Ranching practices, in particular poor grazing frequency of three to four years, these fires more management and fire suppression, also have had likely occurred at one- or two-year intervals for a profound impact on the vegetation of Oklaho-

- 14. 11 ma. Historically, large herbivores such as bison, be destroyed by plowing or urbanization. Thus, elk, mule deer, white-tailed deer, pronghorn an- restoration efforts can be accomplished on many telope, and small grazing/browsing mammals sites where native plant communities still exist. were attracted to areas that had been recently Patterns of grazing — varying from continu burned and formed a mosiac with unburned sites ous year-round stocking to multiple-paddock (Truett et al., 2001). These animals rotationally rotations with cross-fencing and many moves grazed prairies, shrublands, and forests based on during the grazing season — also have a pro- the scale and timing of fires (Engle and Bidwell, found impact on Oklahoma’s vegetation types, 2001). They congregated on the burned sites for especially the biological diversity of each. Differ the entire growing season or until the forage was ent grazing systems produce different landscape gone. They then moved to another burn site, usu- patterns, different plant community composition, ally the most recently burned. Thus, the historical and different habitat structure. For example, landscape structure, landscape pattern, and com- uneven grazing patterns under season-long and position of the plant communities present were year-long continuous grazing create a condition directly affected by the fire-grazing interaction of shortgrasses and bare ground interspersed or what we now call patch-burn/patch-graze among lightly grazed bunches of tall grasses. (Steuter, 1986; Fuhlendorf and Engle, 2001). Research studies indicate that continuous graz- The arrival in the 1800s of relocated Native ing at light to moderate stocking rates provides American tribes and European settlers drastically the best individual animal performance and a altered these ecological interactions. Fencing, for moderate level of habitat diversity in Oklahoma. example, prevented natural animal movement Importantly, it also provides the desired habitat and allowed areas to be stocked with more cattle structure and composition needed for wildlife than the land could support. Repeated grazing of species such as Northern Bobwhite Quail, Great- the grasses and forbs that constitute the fine fuels er-prairie Chicken, and Lesser-prairie Chicken. supporting fire reduced them to levels at which Rotational grazing with cross-fencing has fire was no longer a driving ecological force on been advocated to enhance animal performance, the landscape. As a result, woody plants began to prevent spot grazing, and improve grazing increase, the grasses and forbs declined further, distribution. This approach is based on mostly and the native plant communities present began unsupported claims and folk lore. For example, to degrade. proponents have suggested that moving cattle Today, improper grazing by livestock is still controlled by fencing from grazed to ungrazed a significant problem throughout the state. Two areas mimics the historical grazing patterns of terms commonly used to denote improper graz- the native, large herbivores such as bison and ing are overuse and overgrazing. Overuse by elk. This proposition is erroneous and has no livestock means that the plants are too short (leaf basis in science or historical evidence. As noted area needed for photosynthesis too reduced) to above, historical observations and contemporary maintain their vigor and thus persist at the site. research clearly demonstrate that grazing and As the preferred grazing plants decline or die, browsing animals are attracted to plants with other plants, usually those less palatable to the the highest forage quality that occur in the most grazing animals, replace them. A measurable recently burned area. Animals will spend most of change in the composition of the vegetation at the their time on the burned area until higher quality site as the result of overuse is defined as overgraz forage is available elsewhere. ing. This change is easily reversed by a change A significant drawback to rotational grazing in management in a relatively short period of with cross-fencing is that it reduces the structural time in the wetter central and eastern parts of and compositional diversity of an ecological site, Oklahoma. In contrast, in the drier western part, and thus reduces habitat quality for many wildlife measurable changes may take several years or species. An approach that mimics historical fire decades to occur. Fortunately, Oklahoma’s native and grazing patterns is the patch-burn/patch- plant communities are very resilient and can only graze system (Fuhlendorf and Engle, 2001).

- 15. 12 References Hedrick, editors. Restoration of Old-growth Beilmann, A.P. and L.G. Brenner. 1951. The recent Forests in the Interior Highlands of Arkansas intrusion of forests in the Ozarks. Annals of and Oklahoma. Proceedings of a Conference, the Missouri Botanical Garden 38:261-282. Winrock International, Morrilton, Arkansas. Blair, W.F. and T.H. Hubbell. 1938. The biotic Delcourt, P.A. and H.R. Delcourt. 1987. Long- districts of Oklahoma. American Midland term forest dynamics of the temperate zone. Naturalist 20:425-454. Ecological Studies 63. Springer-Verlag Inc., Branson, C.C. and K.S. Johnson. 1972. General- New York. ized geologic map of Oklahoma. p. 4. IN: Duck, L.G. and J.B. Fletcher. 1943. A Game Type Johnson, K.S., C.C. Branson, N.E. Curtis Jr., Map of Oklahoma. A Survey of the Game W.E. Ham, W.E. Harrison, M.V. Marcher, and Fur-bearing Animals of Oklahoma. Okla- and J.F. Roberts. 1979. Geology and Earth Re- homa Department of Wildlife Conservation, sources of Oklahoma. An Atlas of Maps and Oklahoma City. Cross Sections. Oklahoma Geological Survey Duck, L.G. and J.B. Fletcher. 1945. The game Education Publication Number 1. Norman, types of Oklahoma: introduction. IN: A Sur- Oklahoma. vey of the Game and Fur-bearing Animals of Bruner, W.E. 1931. The vegetation of Oklahoma. Oklahoma. State Bulletin No. 3. Oklahoma Ecological Monographs 1:99-188. Department of Wildlife Conservation, Okla- Buckner, E. 1989. Evolution of forest types in the homa City. Southeast. pp 27-34. In T.A. Waldrop, editor. Engle, D.M. and T.G. Bidwell. 2001. Viewpoint: Proceedings of Pine-hardwood Mixtures: A the response of central North American prai- Symosium on Management and Ecology of ries to seasonal fire. Journal of Range Manage- the Type. General Technical Report SE-58. ment 54:2-10. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Ser- Featherly, H.I. 1943. The cavalcade of botanists vice. Southern Forest Experiment Station, in Oklahoma. Proceedings of the Oklahoma Asheville, North Carolina. Academy of Science 23:9-13. Carter, B.J. 1996. General Soil Map of Oklahoma. Federal Geographic Data Committee (FDGC). Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station, 1997. Vegetation Information and Classifica- Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural tion Standard. Vegetation Subcommittee for Resources, Oklahoma State University, Still- Classification and Information Standards. water, Oklahoma. United States Geological Survey, Reston, Currey, B.R. 1970. Climate of Oklahoma. U.S. Virginia. Department of Commerce. Climatology Foti, T.L. and S.M. Glenn. 1991. The Ouachita of the United States Series. Number 60-34. Mountain landscape at the time of settlement. Washington, D.C. pp 49-65. In D. Henderson and L.D. Hedrick, Curtis, N.E. Jr. and W.E. Ham. 1972. Geomorphic editors. Restoration of Old Growth forests in provinces of Oklahoma. p. 3. IN: Johnson, the Interior Highlands of Arkansas and Okla- K.S., C.C. Branson, N.E. Curtis Jr., W.E. Ham, homa. Proceedings of a Conference, Winrock W.E. Harrison, M.V. Marcher, and J.F. Roberts. International, Morrilton, Arkansas. 1979. Geology and Earth Resources of Okla- Francaviglia, R.V. 2000. The Cast Iron Forest. homa. An Atlas of Maps and Cross Sections. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas. Oklahoma Geological Survey Education Pub- Fuhlendorf, S.D. and D.M. Engle. 2001. Restor- lication Number 1. Norman, Oklahoma. ing heterogeneity on rangelands: ecosystem Delcourt, H.R. and P.A. Delcourt. 1991. Late- management based on evolutionary grazing quaternary vegetation history of the interior patterns. Bioscience 51:625-632. highlands of Missouri, Arkansas, and Okla- Gibson, A.M. 1965. Oklahoma: A History of Five homa. pp 15-30. In D. Henderson and L.D. Centuries. Harlow Publishing, Norman, Oklahoma.

- 16. 13 Grimm, E.C. 1984. Fire and other factors control- Nuttall, T. (S. Lottinville, editor). 1980. A Journal ling the Big Woods vegetation of Minnesota of Travels into the Arkansas Territory During in the mid-nineteenth century. Ecological the Year 1819. University of Oklahoma Press, Monographs 54:291-311. Norman, Oklahoma. Hoagland, B. 2000. The vegetation of Oklahoma: Oklahoma Climatological Survey. 1997. Climate a classification for landscape mapping and of Oklahoma. Statewide Precipitation and conservation planning. Southwestern Natu- Temperature Maps. Oklahoma Climatological ralist 45:385-420. Survey, College of Geosciences, University Johnson, K.S., C.C. Branson, N.E. Curtis Jr., W.E. of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma. http:// Ham, W.E. Harrison, M.V. Marcher, and J.F. www.ocs.ou.edu. Roberts. 1979. Geology and Earth Resources Steuter, A.A. 1986. Fire behavior and standing of Oklahoma. An Atlas of Maps and Cross crop characteristics on repeated seasonal Sections. Oklahoma Geological Survey burns – northern mixed prairie. pp. 54-59. Education Publication Number 1. Norman, IN A.L. Koonce, editor. Prescribed Burning Oklahoma. in the Midwest: State-of-the-Art. Proceedings Lewis, A. 1924. LaHarpe’s first expedition in of a Symposium, University of Wisconsin at Oklahoma, 1718-1719. Chronicles of Okla- Stevens Point. homa 2:331-349. Truett, J.C., M. Phillips, K. Kunkel, and R. Miller. Masters, R.E., J.E. Skeen, and J. Whitehead. 2001. Managing bison to restore biodiversity. 1995. Preliminary fire history of McCurtain Great Plains Research 11:123-144. County Wilderness Area and implications for Wyckoff, D.G. and L.R. Fisher. 1985. Preliminary red-cockaded woodpecker management. pp. testing and evaluation of the Grobin Davis 290-302. In D.L. Kulhavy, R.G. Hooper, and archeological site, 34Mc-253, McCurtain R. Costa, editors. Red-cockaded woodpecker: County, OK. Archaeological Resource Survey Species Recovery, Ecology and Management. Report 22. Oklahoma Archeological Survey, Center for Applied Studies, Stephen F. Austin Norman, Oklahoma. University, Nacogdoches, Texas.

- 17. 14 NOTES

- 18. 15

- 19. 16