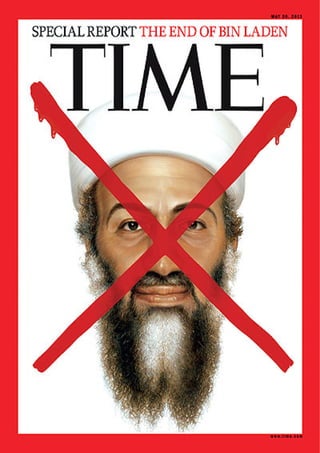

Time special report - the end of Bin Laden

- 3. COVER Killing bin Laden: How the U.S. Finally Got Its Man By DAVID VON DREHLE Wednesday, May 04, 2011 A jubilant crowd of mostly college students celebrated in front of the White House the night bin Laden's death was announced by the President Brooks Kraft for TIME The Four Helicopters chuffed urgently through the Khyber Pass, racing over the lights of Peshawar and down toward the quiet city of Abbottabad and the prosperous neighborhood of Bilal Town. In the dark houses below slept doctors, lawyers, retired military officers — and perhaps the world's most wanted fugitive. The birds were on their way to find out. Ahead loomed a strange-looking house in a walled compound. The pilots knew it well, having trained for their mission using a specially built replica. The house was three stories tall, as if to guarantee a clear view of approaching threats, and the walls were higher and thicker than any ordinary resident would require. Another high wall shielded the upper balcony from view. A second smaller house stood nearby. As a pair of backup helicopters orbited overhead, an HH-60 Pave Hawk chopper and a CH-47 Chinook dipped toward the compound. A dozen SEALs fast-roped onto the roof of a building from the HH-60 before it lost its lift and landed hard against a wall. The Chinook landed, and its troops clambered out. Half a world away, it was Sunday afternoon in the crowded White House Situation Room. President Barack Obama was stone-faced as he followed the unfolding drama on silent video screens — a drama he alone had the power to start but now was powerless to control. At a meeting three days earlier, Obama had heard his options summarized, three ways of dealing with tantalizing yet uncertain intelligence that had been developed over painstaking months and years. He could continue to watch the strange compound using spies and satellites in hopes that the prey would reveal himself. He could knock out the building from a safe distance using B-2 bombers and their precision-guided payloads. Or he could unleash the special force of SEALs known as Team 6.

- 4. How strong was the intelligence? he asked. A 50% to 80% chance, he was told. What could go wrong? Plenty: a hostage situation, a diplomatic crisis — a dozen varieties of the sort of botch that ruins a presidency. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter authorized a daring helicopter raid on Tehran to free American hostages. The ensuing debacle helped bury his re-election hopes. To wait was to risk a leak, now that more than a hundred people had been briefed on the possible raid. To bomb might mean that the U.S. would never know for sure whether the mission was a success. As for an assault by special forces, U.S. relations with the Pakistani government were tricky enough without staging a raid on sovereign territory. It is said that only the hard decisions make it to a President's plate. This was one. Obama's inner circle was deeply divided. After more than an hour of discussion, Obama dismissed the group, saying he wanted time to reflect — but not much time. The next morning, as the President left the White House to tour tornado damage in Alabama, he paused on his way through the Diplomatic Reception Room to render his decision: send the SEALs. On Saturday the weather was cloudy in Abbottabad. Obama kept his appointment at the annual White House Correspondents' Dinner, where a ballroom full of snoops had no inkling of the news volcano rumbling under their feet. The next morning, White House officials closed the West Wing to visitors, and Obama joined his staff in the Situation Room as the mission lifted off from a base in Jalalabad, southern Afghanistan. The bet was placed: American choppers invaded the airspace of a foreign country without warning, to attack a walled compound housing unknown occupants. Obama returned to the Situation Room a short time later as the birds swooped down on the mysterious house. Over the next 40 minutes, chaos addled the satellite feeds. A hole was blown through the side of the house, gunfire erupted. SEALs worked their way through the smaller buildings inside the compound. Others swarmed upward in the main building, floor by floor, until they came to the room where they hoped to find their cornered target. Then they were inside the room for a final burst of gunfire. What had happened? The President sat and stared while several of his aides paced. The minutes "passed like days," one official recalls. The grounded chopper felt like a bad omen. Then a voice briskly crackled with the hoped-for code name: "Visual on Geronimo." Osama bin Laden, elusive emir of the al-Qaeda terrorist network, the man who said yes to the 9/11 attacks, the taunting voice and daunting catalyst of thousands of political murders on four continents, was dead. The U.S. had finally found the long-sought needle in a huge and dangerous haystack. Through 15 of the most divisive years of modern American politics, the hunt for bin Laden was one of the few steadily shared endeavors. President Bill Clinton sent a shower of Tomahawk missiles down on bin Laden's suspected hiding place in 1998 after al-Qaeda bombed two U.S. embassies in Africa. President George W. Bush dispatched troops to Afghanistan in 2001 after al-Qaeda destroyed the World Trade Center and damaged the Pentagon. Each time, bin Laden escaped, evaporating into the lawless Afghan borderlands where no spy, drone or satellite could find him. Meanwhile, the slender Saudi changed our lives in ways large and small, touched off a moral reckoning over the use of torture and introduced us to the 3-oz. (90 ml) toothpaste tube.

- 5. "Dead or alive," Bush declared in 2001, when the smell of smoke was still acrid, and the cowboy rhetoric struck a chord. It took a long time to make good on that vow — an interval in which the very idea of American power and effectiveness took a beating. Thus, to find this one man on a planet of close to 7 billion, to roar out of the night and strike with the coiled wrath of an unforgetting people, was grimly satisfying. The thousands of Americans across the country whose impulse was to celebrate — banging drums outside the White House, waving flags at Ground Zero — were moved perhaps by more than unrefined delight at the villain's comeuppance. It was a relief to find that America can still fix a bull's-eye on a difficult goal, stick with it year after frustrating year and succeed when almost no one expects it. Living the Good Life So he wasn't in a cave after all. Osama bin Laden, master marketer of mass murder, loved to traffic in the image of the ascetic warrior-prophet. In one of his most famous videotapes, he chose gray rocks for a backdrop, a rough camo jacket for a costume and a rifle for a prop. He portrayed a hard, pure alternative to the decadent weakness of the modern world. Soft Westerners and their corrupt puppet princes reclined in luxury and sin while he wanted nothing but a gun and a prayer rug. The zealot travels light, his bloodred thoughts so pure that even stones are as cushions for his untroubled sleep. Now we know otherwise. Bin Laden was not the stoic soldier that he played onscreen. The exiled son of a Saudi construction mogul was living in a million-dollar home in a wealthy town nestled among green hills. He apparently slept in a king-size bed with a much younger wife. He had satellite TV. This, most of all, was fitting, because no matter how many hours he spent talking nostalgically of the 12th century and the glory of the Islamic caliphate, bin Laden was a master of the 21st century image machine. He understood the power of the underdog to turn an opponent's strength into a fatal weakness. If your enemy spans the globe, blow up his embassies. If he fills the skies with airplanes, hijack some and smash them into his buildings. Bin Laden learned this judo as a mujahid fighting the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, and he perfected it against the U.S. In 1996 he laid down a marker, literally declaring war on the world's lone superpower — an incredibly audacious act of twisted imagination. And then, with patience and cunning, he somehow made the war come true. No Hollywood filmmaker ever staged a more terrifying spectacle than 9/11, which bin Laden conjured from a few box cutters and 19 misguided martyrs. When the Twin Towers collapsed, he became the real-life answer to the ruthless, stateless and seemingly unstoppable villains of James Bond fantasy. It was necessary, then, to find him and render him mortal again, reduce him to mere humanity — not just as a matter of justice but as a matter of self-defense. The raid took him down to size. Obama's chief counterterrorism adviser, John Brennan, found himself disgusted by bin Laden in a whole new way: "Here is bin Laden, who has been calling for these attacks, living in this million-dollar-plus compound, living in an area that is far removed from the front. I think it really just speaks to just how false his narrative has been over the years." Remember that bin Laden once declared, "We love death. The U.S. loves life." Evidently that was a line he peddled to would-be suicide bombers. For himself, he preferred life in tranquil Abbottabad. That proved his undoing. In 2005 an unknown benefactor built the strange compound where bin Laden was eventually found. The site was a triangle-shaped piece of farmland. Walls ranging from 10 ft. (3 m) to

- 6. 18 ft. (5.5 m) high and topped with barbed wire enclosed the 1-acre (0.4 hectare) property, which lay less than a mile from the military academy that is Pakistan's answer to West Point. An interior wall 12 ft. (3.7 m) high separated the house from the rest of the grounds. Thus to reach the living areas, it was necessary to pass through two locked gates. A pit in the yard was used for burning household trash, leaving nothing for snooping garbage collectors. On the north side of the house, where the windows were visible, the glass was opaque. Bin Laden took up residence soon after the compound was finished. Perhaps he knew of other terrorists in the area. Earlier this year, Umar Patek, an Indonesian linked to the 2002 al-Qaeda bombing in Bali, was arrested at the home of an Abbottabad retiree. Patek's capture came not long after Pakistani authorities arrested an alleged al-Qaeda facilitator named Tahir Shehzad. According to documents published by WikiLeaks, bin Laden's senior lieutenant in the period after Tora Bora, Abu Faraj al-Libbi, lived for a time in Abbottabad before his capture in 2005 and was visited there by one of bin Laden's trusted couriers. But if bin Laden knew that this pretty town with its rolling golf course was home to sympathizers, he should have surmised that it was also home to his enemies. And a person who truly wants to stay hidden should not live in a big house behind towering walls in an otherwise sparsely populated field. People are bound to grow curious — including people working for the CIA. "Once we came across this compound, we paid close attention to it because it became clear that whoever was living here was trying to maintain a very discreet profile," a senior U.S. intelligence operative explained. Brennan summed it up more tersely: "It had the appearance of sort of a fortress." In Plain Sight By the time of the raid, Bin Laden had been living in the compound for some five years, surrounded by members of his extensive family, including the adult son who died with him. Why did it take so long for the fortress to come under suspicion? Obama's view was clear in his televised address from the East Room late Sunday night, when he delivered the news of bin Laden's death to a stunned global audience. He subtly reprised the charge he had made during his campaign for the presidency: the Bush Administration took its eye off the ball. "Over the last 10 years, thanks to the tireless and heroic work of our military and our counterterrorism professionals, we've made great strides" in the war against al-Qaeda, he said. "Yet Osama bin Laden avoided capture." Obama continued, "And so shortly after taking office, I directed Leon Panetta, the director of the CIA, to make the killing or capture of bin Laden the top priority of our war against al-Qaeda, even as we continued our broader efforts to disrupt, dismantle and defeat his network." The implication wasn't lost on Bush's supporters. While the former President and his senior advisers were quick to praise the successful raid, other Republicans groused about the way it was framed. "That's Obama politics," Senator Saxby Chambliss of Georgia, the ranking Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee, told Time. He continued, "I can tell you I was involved in a very close way with the Bush Administration — Director [Michael] Hayden when he was at the CIA, as well as Director [Porter] Goss when he was there, and Director [George] Tenet. I know that the focus of everyone in the Bush Administration was to take out bin Laden irrespective of what it took. They never lost their focus."

- 7. A larger and more pressing question was the failure of Pakistan to note the terrorist chieftain's luxury digs. Abbottabad is just 75 winding highway miles (120 km) from the capital, Islamabad, and teems with Pakistani military brass — current, future and retired. It is home to an entire brigade of the Pakistani army. How could the world's most wanted terrorist spend five years in a fortress compound under the nose of the government? White House adviser Brennan said it is "inconceivable" that bin Laden didn't have a support system inside Pakistan. "The United States provides billions of dollars in aid to Pakistan," says Democratic Senator Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey." Before we send another dime, we need to know whether Pakistan truly stands with us in the fight against terrorism." For President Asif Ali Zardari, the charge that Pakistan shielded bin Laden is a personal affront. He blames the al-Qaeda leader for the murder of his wife, former President Benazir Bhutto, who was, as Zardari wrote in the Washington Post, "bin Laden's worst nightmare — a democratically elected, progressive, moderate, pluralistic female leader." Zardari moved quickly after the raid to tamp down possible protests, noting that the Taliban was blaming him for the al-Qaeda leader's death. "We will not be intimidated," Zardari declared. "Pakistan has never been and never will be the hotbed of fanaticism that is often described by the media." Yet another of the lessons we have learned as a consequence of bin Laden's jihad is that the politics of Pakistan are Byzantine and double-dealing in ways no spy novelist could conjure. Only a week before the raid, news reports revealed that Pakistan — a supposed U.S. ally in the war on terrorism — has been urging Afghan President Hamid Karzai to break with the Americans and team up with China. This is a government, after all, that manages to fight the Taliban with one arm even as elements of its internal spy agency, the Directorate for Inter-Services Intelligence, support the Taliban with the other. As Daniel Markey, a former State Department specialist on South Asia, explains, Pakistan is full of suspicious characters and fortified homesteads. Government officials often decide that it's better not to know too much. So as we ask in coming weeks whether forces inside Pakistan protected bin Laden, pursued him or ignored him, the answer is likely yes to all three. And that should warn us that bin Laden's death resolves only a part of the twisted, complex drama that is the war on terrorism. Indeed, it may be the easy part. From Intel to Capture The path to bin Laden began in the dark prisons of the CIA's post-9/11 terrorist crackdown. Under questioning, captured al-Qaeda operatives described bin Laden's preferred mode of communication. He knew that he couldn't trust electronics, so he passed his orders through letters hand-carried by fanatically devoted couriers. One in particular caught the CIA's attention, though he was known only by a nickname. Interrogators grilled 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed for details about the courier. When he pleaded ignorance, they knew they were onto something promising. Al-Libbi, the senior al-Qaeda figure captured in 2005, also played dumb. Both men were subjected to so-called enhanced interrogation techniques, including, in Mohammed's case, the waterboard. The U.S. previously prosecuted as torturers those who used waterboarding, and critics say it violates international treaties. They also argue that extreme techniques are counterproductive. The report that Mohammed and al-Libbi were more forthcoming after the harsh treatment guarantees that the argument will go on.

- 8. Gradually, the courier's identity was pieced together. The next job was to find him. The CIA tracked down his family and associates, then turned to the National Security Agency to put them under electronic surveillance. For a long time, nothing happened. Finally, last summer, agents intercepted the call they'd been waiting for. The CIA picked up the courier's trail in Peshawar and then followed him until he led them to the compound in Abbottabad. Now the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency trained a spy satellite on the triangular fortress. Over time, despite the residents' extreme secrecy, analysts grew more confident that they had hit the jackpot. "There wasn't perfect visibility on everything inside the compound, but we did have a very good understanding of the residents who were there, in terms of the number there and in terms of who the males were and the women and children," a senior U.S. intelligence official told reporters. "We were able to identify a family at the compound that, in terms of numbers, squared with the number of bin Laden family members we thought were probably living with him in Pakistan." Obama was first informed of the breakthrough in August. By February the clues were solid enough for Panetta to begin planning a raid. Panetta called the commander of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), Vice Admiral William McRaven, to CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. JSOC is the potent weapon created from the humiliation of the failed 1980 hostage-rescue mission. That effort was doomed by inadequate preparation, poor communication and cascading equipment failures. JSOC put an end to those obstacles among the elite U.S. strike forces and has become one of the most effective tools in the American military for dealing with unconventional enemies in the shape-shifting war on terror. Ultimately, the plan devised by McRaven's troops called for about 80 men aboard four helicopters. "I don't want you to plan for an option that doesn't allow you to fight your way out," Obama told his military planners. Darkness was the cloak and speed essential; the force had to be in and out of Pakistan before the Pakistani military could respond. They rehearsed against a 30-minute clock. The orders were capture or kill. Meanwhile, the pace of secret White House briefings accelerated in March and April, culminating in the April 28 session at which Obama weighed the conflicting advice of his senior circle. When the decision was made to strike the compound, bin Laden still had not been spotted among the residents behind the walls. The raiders found him near the end of their search through the house. The courier was already dead on the first floor, along with his brother and a woman caught in the cross fire. When the SEALs encountered bin Laden, he was with one of his wives. The young woman started toward the SEALs and was shot in the leg. Bin Laden, unarmed, appeared ready to resist, according to a Defense Department account. In an instant it was over: in all, four men and one woman lay dead. Bin Laden was shot in the head and in the chest. One of bin Laden's wives confirmed his identity even as a photograph of the dead man's face was relayed for examination by a face-recognition program. As the SEAL team prepared to load the body onto a helicopter, at Langley McRaven delivered the verdict. His voice was relayed to the White House Situation Room: "Geronimo: E-KIA," meaning enemy — killed in action.

- 9. "We got him," Obama said. The strike force had eluded Pakistani radar on the flight into the country, but once the firefight erupted, the air force scrambled jets, which might arrive with guns blazing. A decision was made to destroy the stricken chopper. Surviving women and children in the compound — some of them wounded — were moved to safety as the explosives were placed and detonated. In the meantime, SEALs emerged from the house carrying computer drives and other potential intelligence treasures collected during a hasty search. Aloft, the raiders performed a head count to confirm that they hadn't lost a man. That news sent a second wave of smiles through the Situation Room. "They said all the helicopters are up, none of our people are hurt," a senior Administration official told TIME. "That was actually the period of most relief." DNA from the body was matched to known relatives of bin Laden's — a third form of identification. According to officials, the dead man's next stop was the U.S.S. Carl Vinson, an aircraft carrier in the Arabian Sea. There, his body was washed and wrapped in a white sheet, then dropped overboard. There would be no grave for his admirers to venerate. The face that haunted the Western world, the eyes that looked on the blazing towers with pride of authorship, sank sightless beneath the waves. What He Leaves Behind On Sept. 17, 2001, the same day that President Bush promised "dead or alive," Secretary of State Colin Powell — already a seasoned veteran of the hunt for bin Laden — had this to say: "We are after the al-Qaeda network. It's not one individual; it's lots of individuals, and it's lots of cells. Osama bin Laden is the chairman of the holding company, and within that holding company are terrorist cells and organizations in dozens of countries around the world, any one them capable of committing a terrorist act." The hunt for bin Laden was only one aspect of the war that he unleashed. It has been a war unlike any other, one that defies definition. It has persisted in Afghanistan long after bin Laden and his enabler Mullah Omar were driven from the country. It bled into Iraq without Americans being able to agree whether we had chased or created it there. It is a gray war, without borders or uniforms, fought on frontiers ranging from the rocky highlands of the Silk Road to the aisles of the suburban beauty-supply warehouse where an al-Qaeda trainee bought chemicals to make a bomb. You can't ignore the war, because it can come and find you when you least expect it. So while it's not enough to get one individual, the occasion of bin Laden's death is a moment to take stock. A scattered enemy can still be a dangerous one. Terrorism experts warn of the possibility that an isolated cell or lone wolf might try to strike in retaliation for the killing of the leader. But the al-Qaeda network is a tattered tissue compared with what it was when it managed to hit the American mainland as it had never been hit by outsiders before. According to polling by the Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project, across the Muslim world confidence in bin Laden had plunged long before his death — down by half in the Palestinian territories, by even more in Indonesia, Jordan and, yes, Pakistan.

- 10. From Tunisia to Egypt to Syria this year, scores of thousands of young people — the very people bin Laden hoped to lead backward across a millennium — have poured into the streets in peaceful uprisings, chanting slogans of democracy. To be sure, Islamic fundamentalists will seek to turn the Arab Spring in their own direction, but regardless of how that plays out, it has been a bad season for bin Ladenism. The successes against al-Qaeda have cost us dearly — in money, time, easy freedom and untroubled sleep. It has cost the lives of more than 5,000 U.S. and allied service members while leaving many more thousands wounded. The war on terrorism is nearly 10 years old and has no clear end in sight. But perhaps the most important thing to come from bin Laden's death is the sense that maybe this struggle won't last forever. That hope seemed to animate the young people who greeted the news Sunday night with jubilation. Outside the White House, college students turned Pennsylvania Avenue into a giant party, waving flags and chanting "U.S.A.!" They shimmied trees, sang patriotic songs and hugged strangers like sailors on V-J Day. Similar celebrations broke out across the country, but the next day a more contemplative mood settled over people whose lives were marked by 9/11. People like Ben Hughes, 21, a junior at Savannah College of Art and Design, who typed this Facebook message on the first day without Osama bin Laden: "I was a sixth grade student in Chatham, MA. I distinctly remember walking into school that morning with two friends, one of whom had his birthday that day and was planning a party. When the first plane hit, we were all ushered to the main hallway and made to take seats on the floor for an announcement from our principal. She told us that it seemed an accident had occurred with one of the World Trade Center buildings in New York City. A pilot may have suffered a heart attack at the helm of the aircraft and hit the building, she said. "We continued our day without access to television or news outlets. But you could see that the teachers knew more than they let on. When I arrived home I asked my mother if I could watch the news reports, and for what seemed like days we sat there, in both awe and terror. It was the first moment in my short life where I felt entirely helpless. "In the years since that day I have marked every year with a solid time of reflection and silence. And I will always remember also that I was on a flight between Charlotte, NC and Savannah, GA when the pilot came over the loudspeaker to announce that Osama bin Laden had been killed." The innocence lost can never be restored. But the feeling of helplessness need not last forever. It is an older, wiser country that writes the epitaph of the terrorist.

- 11. Obama 1, Osama 0 By JOE KLEIN Friday, May 20, 2011 White House Situation Room, Sunday, May 1. The "minutes passed like days" Pete Souza / White House Sometimes the tabloid route is best: Obama got Osama. President Barack Hussein Obama approved the attack that killed his near namesake Osama bin Laden the very same week that Obama revealed his long-form birth certificate, addressing a silly dispute that was really about something heinous and serious: the suspicion of far too many Americans that the President was not who he said he was, that he was a secret Muslim and maybe not even playing for our team. All such doubts are resolved now, by document and deed, although the various birthers and truthers and mouthers will continue to play their vile games. But the facts are there for posterity and for the voters who will have to make a judgment in 2012: this profoundly American President ran an exquisite operation to find and kill one of the great villains of history. In the process, U.S. presidential politics and the so-called war on terror were transformed dramatically; suddenly, both foreign policy experts and Republican candidates for President had vast new landscapes to consider. And so much for No Drama, by the way. there is no measure of competence the public takes more seriously than a President's performance as Commander in Chief. On the most basic level, the bin Laden raid was a vivid demonstration of how this Commander in Chief operates. He is discreet, precise, patient and willing to be lethal. He did not take the easy route, which would have been a stealth-bomber strike on bin Laden's compound. He ordered the Navy SEAL operation, even though there were myriad ways it could have failed — or turned out to be an embarrassment if bin Laden hadn't been there, or a disaster if the SEALs had been slaughtered, or if a helicopter had been damaged (as several aircraft were when Jimmy Carter tried to rescue the hostages from Iran). In at least nine National Security Council meetings, Obama insisted on reviewing every crucial detail of the operation. He made sure, after a decade of witless Islam-related goofs by U.S. leaders, that bin Laden's body would be handled and consigned to the lower depths in a way that would not offend Muslims; that in the early hours, at least, there wouldn't be gory photos or films or any evidence of barbaric gloating; that the operation would be surgical and stealthy enough that bin Laden's document hoard would be preserved and dispositive DNA evidence would be gathered. These are the sort of nuances — a word his predecessor mocked — that have marked many of Obama's foreign policy

- 12. decisions, made in a deliberative style that his critics, and even some supporters, have seen as evidence of dithering or indecision. George W. Bush certainly deserves some of the credit for this raid. It would not have been possible without his decision to amp up human-intelligence assets and special-operations forces after decades of neglect. But you have to wonder whether Bush would have had the patience or subtlety to conduct this operation with the same thoroughness Obama did. Bush certainly lacked the strategic focus to understand that the war against al-Qaeda had to be primarily a slow-moving special-forces affair; he was diverted into bold gestures, like the disastrous war in Iraq. He never studied the intelligence rigorously enough; he bought the sources that backed his predispositions. He understood too late the style and substance of Islam, how words like crusade resonated through the region. His was a bumper-sticker foreign policy. His speeches were full of God and Freedom and Evildoers. His troops rushed into Baghdad in three weeks, and he celebrated their victory with another bumper sticker: MISSION ACCOMPLISHED. He was able to use these simplicities to win re-election in 2004, although he lost a lot of lives unnecessarily and damaged America's esteem in the eyes of the world. Obama's national-security practices, if not his actual policies, have been almost the exact opposite, almost to a fault. There have been no three-week victories; there have been three-month deliberations about what to do in Afghanistan. There were precious few victories at all before the bin Laden operation. There was a lot of multilateralism and deference to foreign leaders. Critics said Obama bowed too deeply to the Emperor of Japan. There were few dramatic pronouncements and zero foreign policy bumper stickers; there were more than a few embarrassments. He was dissed by the Chinese. He was dissed by the Iranians. He was defied by corrupt nonentities like Afghanistan's Hamid Karzai; he was double-dealt by the Pakistanis. And in recent weeks, there was a growing chorus that his handling of the Arab Spring revolutions had been incoherent and his indulgence in a humanitarian intervention in Libya had been muscled through by a coterie of female policy advisers who were tougher than he was. In the days before the bin Laden raid, Obama's national-security staff was increasingly frustrated with how his foreign policy was being portrayed. He was not indecisive, they argued, just careful. They made a transcript of a crucial Feb. 1 phone call between Obama and Egypt's Hosni Mubarak available to me. It was classic Obama. "I have no interest in embarrassing you," the President said. "I want to help you secure your legacy by ushering in a new era." He worked this track patiently, twice, three times. "I respect my elders," Obama said, "but because things worked one way in the past, that doesn't mean they're going to work the same way in the future. You need to seize this historic moment and leave a positive legacy." Mubarak said he'd think about it and would talk again in a week. Obama said he wanted to talk again the next day. Mubarak said maybe over the weekend; Obama said no: "We'll talk in 24 hours." No threats, but no give, either. "You have to see this in the context of history," a senior Administration official told me. "That's a pretty tough decision to make, involving a longtime U.S. ally. But he was very firm with Mubarak. If you look at Reagan, he agonized far longer over whether to abandon governments we had supported in Indonesia and the Philippines than the President did about Egypt." Last Aug. 12, four months before the Tunisian rebellion began, the President issued a national-security directive ordering his staff to develop a new policy that assumed the governments in the Middle East were rickety and might soon topple. A copy of this memo was provided to me as well.

- 13. Too much has been made of what some are calling Obama's taste for humanitarian intervention. Officials at the National Security Council and the State Department insist that the roles of NSC staffer Samantha Power, U.N. Ambassador Susan Rice and former State Department director of policy planning Anne-Marie Slaughter have been exaggerated. Power is a well-known human-rights activist, but she attended only one meeting with the President on Middle East policy in the past six months; Slaughter is a prominent academic, but she never met with the President on these issues. Indeed, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was leaning against taking military action in Libya until the last moment, when members of the Arab League convinced her that a massacre would take place in Benghazi if nothing were done. The President opposed a no-fly zone because it wouldn't effectively stop a Gaddafi massacre. "He expanded the U.N. resolution to include attacks on Libyan equipment and forces about to move into the city," an Administration official said. "He drove the policy. No one talked him into anything." But there was something incoherent, or perhaps insufficiently explained, about Obama's foreign policy performance. The Libya intervention opened the door to a series of logical questions: Why choose this humanitarian intervention and not others? Why not get involved in Syria, a far more crucial country, where the government was brutally suppressing its citizens and perhaps even conducting massacres? Whom were we actually supporting in Libya? What if the conflict slipped into a tribal stalemate? How were we going to deal with the economic catastrophe looming in Egypt, which Administration officials say is the most pressing problem in the region? Weren't the President's priorities all screwed up? "Libya was tough," the official told me. "The President decided to make a front-end decision to save Benghazi and let our allies carry the burden after that." This policy became the subject of ridicule after an anonymous Administration official called it "leading from the rear." The splendid success of the bin Laden operation should clarify the precise way that this President goes about his work. It also provides an insight into the reasons for Obama's ill-concealed frustration with his critics: the metabolism of policy runs much more slowly than the metabolism of the media. Policy, especially foreign policy, does not lend itself to spiffy one-size-fits-all doctrines. The same President can decide to take a risky shot at killing Osama bin Laden and choose not to take out Muammar Gaddafi; he can decide to make a discreet humanitarian intervention in Benghazi, at the behest of all the countries in the region, while allowing blood to flow in Syria. Not all of these decisions will prove correct over time — every President makes mistakes — but the overall pattern of judgments can be assessed only with sufficient hindsight. It is difficult for a President and his team to keep things in perspective when the media pulse has reached tuning-fork speed and now includes not just CNN and Fox News but also al-Jazeera, Facebook and Twitter. It is particularly difficult for a President whose every decision is questioned by an opposition whose most prominent spokespeople are willing to toy with despicable rumors about his nationality and religious background. "My fellow Americans," the President opened at the White House correspondents' dinner on the night before bin Laden was killed, and the audience roared with laughter. His decimation of Donald Trump, who sat in the audience, was particularly brutal. He marveled at Trump's decision to "fire" Gary Busey instead of Meat Loaf on his Celebrity Apprentice show. "These are the kinds of decisions that would keep me up at night. Well handled, sir." The audience didn't know it at the time, but two nights earlier Obama had been kept up trying to decide whether to launch the SEAL team against bin Laden or take the stealth-bomber route. A President lives at the intersection of historic decisions like that one and a media environment in which Donald Trump can make outlandish claims about the President's birthplace — and

- 14. shoot to the top of Republican presidential polls. The distance between those two worlds is mind-bending. The Obama presidency has been plagued by complexities: How do you conduct a presidency without bumper stickers? How can you explain counterintuitive policies like the need to spend money to soften the blow of a killer recession, even if it expands the federal deficit? How do you convey the policy tightrope that has to be walked as longtime despotic allies in the Arab world are toppled, or not, by revolutions without leaders? How can you explain the delicate task of managing relations with China, when all the public wants to know is why the U.S. seems to be falling behind economically? The one slogan Obama has attempted — WINNING THE FUTURE — seems pretty lame and lamer still when he repeats it incessantly. Why isn't he focused on winning the present? There have been times — his speech after the Tucson, Ariz., shootings, his bin Laden announcement — when the President has tapped directly into the heart of American sensibility and sentiment. More often, he seems a stranger, unable to fix on the momentary needs of the public, unwilling to indulge the instantaneous needs of the media. His strategy is to hope that the accumulated wisdom of his decisionmaking will count for more when 2012 rolls around than the pyrotechnics that pass for political discourse in this jittery, nano-wired age. He will mediate congressional disputes rather than make grand policy proposals that others can shoot down. He will eschew dramatic gestures overseas — unless he has carefully considered every facet, as he did in Abbottabad, Pakistan. He will play the grownup because he is a grownup. It will be interesting to see if that works. The White House Situation Room Through the Years

- 15. War Room President Lyndon B. Johnson, Walt Rostow and others look at relief map of the Khe Sanh area, Vietnam, on February 15, 1968. LBJ's predecessor, President John F. Kennedy created the situation room as an information center in May 1961 after he grew frustrated at the inability to work with real time information during the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Dark Matters President Jimmy Carter participates in a National Security Council Special Coordination Committee meeting on February 3, 1977.

- 16. On the Map President Ronald Reagan meets in the sit room with Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Robert T. Herres (top left) and Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger to discuss the condition of the US missile frigate Stark on May 1, 1987. Panels President Bill Clinton holds a video tele-conference with former South African President Nelson Mandela

- 17. in the situation room on February 22, 2000. Clinton offered continuing US support to Burundi peace talks in a message to participants of Arusha discussions chaired by Mandela. Secure Location President George W. Bush speaks with Iraq's Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki via secure videoconference from the Situation Room at the White House January 4, 2007. Person to Person

- 18. A secure, soundproof telephone cabin, known as a "Superman tube" is seen in the White House Situation Room complex in the basement of the West Wing of the White House, May 18, 2007. The complex went through a major renovation in 2007 — both the size of the suite was enhanced as well as the technological capabilities. Multiple Screens The President and senior staff use the room, seen here May 18, 2007, for regular meetings with of the National Security Council and to talk via secure videoconference with foreign leaders. In times of emergency, the Situation Room becomes a crisis-management center.

- 19. Commander-in-Chief President Barack Obama talks with members of the national security team at the conclusion of one in a series of meetings discussing the mission against Osama bin Laden, in the Situation Room of the White House, May 1, 2011. Photo Essay Crowds, Chaos and Some Closure at Ground Zero Monday, May 2, 2011 | By TIME Photo Department There was perhaps no place more fitting to go than the place where it all began. As President Obama wrapped up his remarks, confirming the death of Public Enemy No. 1, Osama bin Laden, a few people started to gather at New York City’s Ground Zero. They kept coming. By the time a man shinnied up a lamppost around midnight and sprayed bottles of champagne over the crowd, several hundred people had gathered. The word for the night was “closure”. It sprung from the lips of almost every person who went to the hallowed ground of the World Trade Center to mark an end of sorts to the U.S.’s most painful open wound. While capturing bin Laden likely won’t change much of the operations of al-Qaeda, tonight, that didn’t matter. What mattered was the people who gathered to celebrate the conquering of the person who killed many of this city’s loved ones. As everyone knows, in America, when the words are slow to come, the booze pours freely. This colorful crowd, American flags draped around their necks, sang the national anthem, “God Bless the U.S.A.” and “America, the

- 20. Beautiful” in spurts of unison. They chanted “U.S.A.! U.S.A.! U.S.A.!,” “Yes, we can!” (the slogan of Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign) and “Hey, hey, hey, goodbye.” “This is New York — this what we do,” said Sonam Velani, a 23-year-old who lives just a few blocks from the site of the 9/11 WTC attack. “We come together to celebrate these things — even at two in the morning.” One man, wearing what can only be described as stunner shades, clad in an American flag hat and T-shirt, broadcast “Born in the U.S.A.” on a makeshift boom box he held high above his head. Another man scrambled up a pole to address the crowd. “I have something to say. You see what the enemy can do,” he said, gesturing at the empty hole where the Twin Towers once stood. “We will go further.” Lauren Fleishman for TIME A crowd gathered at New York's Ground Zero right after Obama's speech announcing the death of Osama Bin Laden on May 1, 2011. Revelers in the crowd scrambled up light poles over the cheering crowd. As the hours ticked by, the usual antics were to be expected. There were the sellers hawking American flags for $5 a pop, the trampled cardboard cases of Keystone Light (evidence of the drunken college kids who stumbled around looking for more) and the few who took things a little too far, climbing things not meant to be climbed. But in looking for the quieter ones, the people standing solemnly at the back of the crowd, it was easy to spot those who had journeyed to Ground Zero not for a boisterous celebration but to reflect on the magnitude of the night. Among them was Mickey Carroll, a 29-year-old firefighter from Staten Island who lost his father, also a firefighter, on 9/11. He couldn’t quite sum up the emotions he felt. “It’s hard to explain. I feel anxious. I feel excited,” he said. “This is something that this country [EM] these families, my family [EM] has been waiting for for so long.” Jamie Roman, a 17-year-old from Astoria, Queens, who came to Ground Zero with her mother, echoed that sentiment. Holding a T-shirt tightly to her chest, she fought tears as she remembered the man it memorialized. She spoke of

- 21. Christopher Santora, a close family friend who, at 23, was the youngest firefighter to lose his life in the attacks. “This is a little bit of closure,” she said. “We finally have some peace in our lives.” By Kayla Webley, with reporting by Paul Moakley Emotions ran high among those gathering from solemn to excited. A young student Kathleen Lampert sings along to God Bless America with the crowd.

- 22. Young servicemen of the U.S. Army drove into the city from Yonkers, New York to join the gathering. Much of the crowd was made up of young college students who came with all kinds of flags. The crowd held handmade signs to celebrate including this impromptu one on an iPad.

- 23. There were sellers hawking American flags for $5 a pop like Lance (who would only give his first name) early on in the gathering. Some young visitors purchased them from the competing vendors to celebrate with the crowd.

- 24. Those driving by Ground Zero blew their horns to the delight of the crowds. 20-year-old Chris Lombari, the son of a firefighter from Staten Island, climbed on top of a phone booth to cheer on the crowd and reflect on the night.

- 25. It was an emotional night for many of those who attended the impromptu gathering and a time to be close with friends. The crowd made lots of noise with patriotic chants, boom boxes and all kinds of horns.

- 26. From left: Andrea Osbourne and Jessica Davis from F.I.T. celebrated with some patriotic makeup. An excited young man raised the spirits of the crowd while waving a tattered flag over the streets.

- 27. A young man gets a lift from his friend to wave a flag over the crowd. The word for the night was "closure". It sprung from almost every persons' lips who came to the hallowed ground of the World Trade Center to mark an end of sorts to our nation's most painful open wound. Many where young patriotic men waving or wrapping themselves in the stars and stripes.

- 28. Amid the cheers it was easy to spot those who had come to Ground Zero not for the boisterous celebration, but to reflect on the magnitude of the night. Michael Carroll, 27 years old from Ladder 120 in Brownsville, Brooklyn who lost his father, also a firefighter, on 9/11. He couldn't quite sum up the emotions he felt. "It's hard to explain. I feel anxious. I feel excited," he said. "This is something that this country, these families, my family, has been waiting for for so long."

- 29. The crowd grew to several hundred people by 1:00am cheering slogans like "USA! USA! USA!" and "Yes, We Can!" (the slogan of Obama's 2008 campaign). A Long Time Going By PETER BERGEN Friday, May 20, 2011 Bin Laden enjoys a laugh in the Jalalabad region of Afghanistan in 1988 AFP/Getty Images Osama bin Laden long fancied himself something of a poet. His compositions tended to the morbid, and a poem written two years after 9/11 in which he contemplated the circumstances of his death was no

- 30. exception. Bin Laden wrote, "Let my grave be an eagle's belly, its resting place in the sky's atmosphere amongst perched eagles." As it turns out, bin Laden's grave is somewhere at the bottom of the Arabian Sea, to which his body was consigned after his death in Pakistan at the hands of U.S. Navy SEALs. If there is poetry in bin Laden's end, it is the poetry of justice, and it calls to mind what President George W. Bush had predicted would happen in a speech he gave to Congress just nine days after 9/11. In an uncharacteristic burst of eloquence, Bush asserted that bin Laden and al-Qaeda would eventually be consigned to "history's unmarked grave of discarded lies," just as communism and Nazism had been before them. Though bin Laden's body may have been buried at sea on May 2, the burial of bin Ladenism has been a decade in the making. Indeed, it began on the very day of bin Laden's greatest triumph. At first glance, the 9/11 assault looked like a stunning win for al-Qaeda, a ragtag band of jihadists who had bloodied the nose of the world's only superpower. But on closer look it became something far less significant, because the attacks on Washington and New York City did not achieve bin Laden's key strategic goal: the withdrawal of the U.S. from the Middle East, which he imagined would lead to the collapse of all the American-backed authoritarian regimes in the region. Instead, the opposite happened: the U.S. invaded and occupied first Afghanistan and then Iraq. By attacking the American mainland and inviting reprisal, al-Qaeda — which means "the base" in Arabic — lost the best base it had ever had: Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. In this sense, 9/11 was similar to another surprise attack, that on Pearl Harbor on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, a stunning tactical victory that set in motion events that would end in the defeat of imperial Japan. Shrewder members of bin Laden's inner circle had warned him before 9/11 that antagonizing the U.S. would be counterproductive, and internal al-Qaeda memos written after the fall of the Taliban and later recovered by the U.S. military show that some of bin Laden's followers fully understood the folly of the attacks. In 2002 an al-Qaeda insider wrote to another, saying, "Regrettably, my brother ... during just six months, we lost what we built in years." The responsibility for that act of hubris lies squarely with bin Laden: despite his reputation for shyness and diffidence, he ran al-Qaeda as a dictatorship. His son Omar recalls that the men who worked for his father had a habit of requesting permission before they spoke with their leader, saying, "Dear prince, may I speak?" Joining al-Qaeda meant taking a personal religious oath of allegiance to bin Laden, just as joining the Nazi Party had required swearing personal fealty to the Führer. So bin Laden's group became just as much a hostage to its leader's flawed strategic vision as the Nazis were to Hitler's. The key to understanding this vision and all of bin Laden's actions was his utter conviction that he was an instrument of God's will. In short, he was a religious zealot. That zealotry first revealed itself when he was a teenager. Khaled Batarfi, a soccer-playing buddy of bin Laden's on the streets of Jidda, Saudi Arabia, where they both grew up, remembers his solemn friend praying seven times a day (two more than mandated by Islamic convention) and fasting twice a week in imitation of the Prophet Muhammad. For entertainment, bin Laden would assemble a group of friends at his house to chant songs about the liberation of Palestine.

- 31. Bin Laden's religious zeal was colored by the fact that his family had made its vast fortune as the principal contractor renovating the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, which gave him a direct connection to Islam's holiest places. In his early 20s, bin Laden worked in the family business; he was a priggish young man who was also studying economics at a university. His destiny would change with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979. The Afghan war prompted the billionaire's son to launch an ambitious plan to confront the Soviets with a small group of Arabs under his command. That group eventually provided the nucleus of al-Qaeda, which bin Laden founded in 1988 as the war against the Soviets began to wind down. The purpose of al-Qaeda was to take jihad to other parts of the globe and eventually to the U.S., the nation he believed was leading a Western conspiracy to destroy true Islam. In the 1990s bin Laden would often describe America as "the head of the snake." Jamal Khalifa, his best friend at the university in Jidda and later also his brother-in-law, told me bin Laden was driven not only by a desire to implement what he saw as God's will but also by a fear of divine punishment if he failed to do so. So not defending Islam from what he came to believe was its most important enemy would be disobeying God, something he would never do. In 1997, when I was a producer for CNN, I met with bin Laden in eastern Afghanistan to film his first television interview. He struck me as intelligent and well informed, someone who comported himself more like a cleric than like the revolutionary he was quickly becoming. His followers treated bin Laden with great deference, referring to him as "the sheik," and hung on his every pronouncement. During the course of that interview, bin Laden laid out his rationale for his plan to attack the U.S., whose support for Israel and the regimes in Saudi Arabia and Egypt made it, in his mind, the enemy of Islam. Bin Laden also explained that the U.S. was as weak as the Soviet Union had been, and he cited the American withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970s as evidence for this view. He poured scorn on the notion that the U.S. thought of itself as a superpower "even after all these successive defeats." That would turn out to be a dangerous delusion, which would culminate in bin Laden's death at the hands of the same U.S. soldiers he had long disparaged as weaklings. Now that he is gone, there will inevitably be some jockeying to succeed him. A U.S. counterterrorism official told me that there was "no succession plan in place" to replace bin Laden. While the Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri had long been his deputy, he is not the natural, charismatic leader that bin Laden was. U.S. officials believe that al-Zawahiri is not popular with his colleagues, and they hope there will be disharmony and discord as the militants sort out the succession. As they do so, the jihadists will be mindful that their world has passed them by. The al-Qaeda leadership, its foot soldiers and its ideology played no role in the series of protests and revolts that have rolled across the Middle East and North Africa, from Tunisia to Egypt and then on to Bahrain, Yemen and Libya. Bin Laden must have watched these events unfold with a mixture of excitement and deep worry. Overthrowing the dictatorships and monarchies of the Middle East was long his central goal, but the Arab revolutions were not the kind he had envisioned. Protesters in the streets of Tunis and Cairo didn't carry placards with pictures of bin Laden's face, and the Facebook revolutionaries who launched the uprisings represent everything al-Qaeda hates: they are secular, liberal and antiauthoritarian, and their ranks include women. The eventual outcome of these revolts will not be to al-Qaeda's satisfaction either,

- 32. because almost no one in the streets of Egypt, Libya or Yemen is clamoring for the imposition of a Taliban-style theocracy, al-Qaeda's preferred end for the states in the region. Between the Arab Spring and the death of bin Laden, it is hard to imagine greater blows to al-Qaeda's ideology and organization. President Obama has characterized al-Qaeda and its affiliates as "small men on the wrong side of history." For al-Qaeda, that history just sped up, as bin Laden's body floated down into the ocean deeps and its proper place in the unmarked grave of discarded lies. Bergen is the director of the national-security-studies program at the New America Foundation. His latest book is The Longest War: The Enduring Conflict Between America and al-Qaeda A Life of Extremes

- 34. When Terror Loses its Grip By FAREED ZAKARIA Friday, May 20, 2011 Bin Laden's sudden, unexpected death unleashed a decade's worth of pent-up anxiety — and relief James Nachtwey for TIME It is a bizarre historical coincidence. President Barack Obama announced to the world that Osama bin Laden was dead on May 1, the very same day that, 66 years earlier, the German government announced that Adolf Hitler was dead. It's fitting that two of history's great mass murderers share a day of death. (Sort of. Hitler actually killed himself a day earlier, but his death was not revealed to the world until the following day.) Both embodied charisma and intelligence deployed in the service of evil — and both were utterly callous about the killing of innocents to further their causes. There are, of course, many differences between Hitler and bin Laden. But one great similarity holds. Hitler's death marked the end of the Nazi challenge from Germany. And bin Laden's death will mark the end of the global threat of al-Qaeda. Let me be clear. Of course, there are still groups that call themselves al-Qaeda in Pakistan, Yemen, North Africa, Somalia and elsewhere. They will still plot and execute terrorist attacks. We will still have to be vigilant and go after them. But the danger from al-Qaeda was always much more than that of a few isolated terrorist attacks. It was an ideological message that we feared had an appeal across the Muslim world of 1.5 billion believers. The organization had created a message of opposition and defiance that was resonating in that world during the 1990s and right after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. A few weeks after 9/11, I wrote an essay titled "Why They Hate Us," exploring the roots of this Muslim rage. I argued that while U.S. foreign policy might be a contributing factor to the unhappiness of Arabs, it could not alone explain the scale, depth and intensity of Islamic terrorism. After all, U.S. foreign policy over the years has victimized many countries in Latin America and killed millions of Vietnamese, and yet you did not see terrorism emanating from those quarters. There was something different about the nature of Arab frustration that had morphed into anti-American terrorism. The central problem, I argued, was that the stagnation and repression of the Arab world — 40 years of tyranny and decay — had led to deep despair and finally to extreme opposition movements. The one

- 35. aspect of Arab society that dictators could not ban was religion. So the mosque became the gathering ground of opposition movements, and Islam — the one language that could not be censored — became the voice of opposition. The U.S. became a target because we supported the Arab autocracies. Al-Qaeda is a Saudi-Egyptian alliance — bin Laden was Saudi; Ayman al-Zawahiri, his deputy, is Egyptian — that was formed to topple the Saudi and Egyptian regimes and others like them. And that is why bin Laden's death comes at a particularly bad moment for the movement he launched. Its founding rationale has been shattered by the Arab Spring of this year. Al-Qaeda believed that the only way to topple the dictatorships of the Arab world was through violence, that participation in secular political processes was heretical and that people wanted and would cheer an Islamic regime. Over the past few months, millions in the Arab world have toppled regimes relatively peacefully, and what they have sought was not a caliphate, not a theocracy, but a modern democracy. The crowds in Cairo's Tahrir Square did not have pictures of bin Laden or al-Zawahiri in their hands as they chanted for President Hosni Mubarak's ouster. Polls around the Muslim world confirm that support for bin Laden has been plummeting over the past five years. As al-Qaeda morphed into a series of small, local groups, the only places it could mount attacks were cafés and subway stations — in other words, against locals. That turned the locals against al-Qaeda. Their "support" for radical jihadism had in any event always been more theoretical than real, a support for a romantic notion of militant opposition to the West and its domination of the modern world. And it was premised on the assumption that any violence would be directed against "them" (the West), not "us" (Muslims). Once the terrorism came home, even people in Saudi Arabia realized that they didn't want to return to the 7th century, and they didn't much like the men who wanted to bomb them back there. Al-Qaeda is not like Hitler's Germany, which was a vast, rich country with a massive army. It never had many resources or people. Al-Qaeda is an idea, an ideology. And it was personified by bin Laden, a man who for his followers represented courage and conviction. Coming from a wealthy family, he had forsaken a life of luxury to fight the Soviet Union in the mountains of Afghanistan and then trained his guns on the U.S. He used literary Arabic, spoke movingly and tried to seduce millions of Muslims. Those who were duly seduced and joined the group swore a personal oath to him. Young men who volunteered for suicide missions were not dying for al-Zawahiri or Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who planned the 9/11 attacks. They were dying for bin Laden. And with bin Laden's death, the cause and the man have both been extinguished. We will battle terrorists for many years to come, but that does not make them a mortal threat to the Western world or its way of life. The existential danger is over. The nature of the operation against bin Laden spotlights a path for the future of the war on terrorism. Presidents George W. Bush and Obama can share the credit for bin Laden's death, as should many in the U.S. government and military. But it is fair to say that Obama made a decision to dramatically expand the counterterrorism aspect of this struggle. He increased the number of special operations in Afghanistan and Pakistan, quadrupled the number of drone attacks on al-Qaeda's senior leadership in Pakistan and devoted new resources and attention to intelligence gathering. (That is one reason why General David Petraeus is leaving his powerful position directing the war in Afghanistan to run the CIA.) This renewed focus paid off in many captures and kills before May 1, and it has finally paid off in the Big One.

- 36. While Bush certainly used counterterrorism to fight al-Qaeda, the signature element of his strategy was nation building. He believed that deposing one of the worst Arab dictators, Saddam Hussein, and delivering democracy to Iraq would shatter al-Qaeda's appeal. The theory was correct, as the Arab Spring has demonstrated: people in the Arab world want democracy, not dictatorship and not theocracy. But in practice it is a very hard task for an outside power to deliver democracy — which first requires political order and stability — to another nation. It is also a task for which militaries are not best suited. The U.S. armed forces have done their best in Iraq and Afghanistan but — despite huge costs in blood and treasure — the results in both nations are mixed at best. Counterterrorism, by contrast, is a task well suited for military power. It requires good intelligence, above all, and then the swiftness, skill and deadly firepower at which U.S. forces excel. The results speak for themselves. The U.S. has inflicted significant and substantial losses on al-Qaeda by decapitating its leadership and keeping the organization on the run, in hiding and in constant fear. It has been a more effective strategy and vastly less costly than trying to clear, hold and build huge parts of Afghanistan in the hope that order, stability, good governance and democracy will eventually flourish there. Along the way, the efforts at nation building have tarnished the image of the American military. The world's greatest fighting force was shown to be unable to deliver stability to Iraq and Afghanistan, had to deal with scandals like the mistreatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq and saw its soldiers losing their once high morale. May 1 changed all that. The image of a smart, wise and supremely competent U.S. has flashed across the globe. The lesson should be clear. An America that uses its military power less promiscuously, more intelligently and in a targeted and focused manner might once again gain the world's respect and fear, if not affection. And an America that can provide a compelling picture of a modern, open society will be a far more attractive model for Arabs than Osama bin Laden's vision of a backward medieval caliphate. A Revival In Langley By MASSIMO CALABRESI Friday, May 20, 2011

- 37. Leon Panetta Michele Asselin / Contour / Getty Images for TIME The spooks weren't even close to being certain that Osama bin Laden was holed up in the 1-acre (0.4 hectare) compound outside Abbottabad, Pakistan, on April 28. CIA Director Leon Panetta explained to President Obama that afternoon that the agency had no hard proof he was there, no pictures or voice-recognition data of his presence, nothing that could guarantee that the world's most-wanted man was sheltering inside. If you had to lay odds on bin Laden's being inside, CIA officers said soberly, it could be as low as 50-50. This was not, by any measure, a slam dunk. But the window for action was closing, Panetta worried. In an interview with TIME, the CIA director (and soon to be the next Secretary of Defense) explained that more than 100 people had already been briefed on the mission, a fact that by itself was making an operation riskier by the day. Panetta was also fearful that bin Laden might move again and the U.S.'s decadelong hunt to bring him to justice would start all over. Besides, Panetta explained, the CIA was confident enough that bin Laden was inside that he felt the President's national-security team was looking at "an obligation and a responsibility on all of us to act." The next day, Obama delivered written authorization for Panetta to run the operation that would kill bin Laden using a Navy Seal team. That marked quite a change. A few years ago, it would have been hard — maybe impossible — to find a politician in Washington willing to bet on a CIA weather forecast, let alone a life-and-death mission of national importance. The CIA, according to a 2005 CIA inspector general's report, had "suffered a systemic failure" in the run-up to the 9/11 attacks when it failed to work with other U.S. agencies to thwart the plot. The agency had been part of the team that lost bin Laden at Tora Bora in December 2001, the last time anyone had a clear idea of where he was. Under pressure from Bush Administration officials to justify a war with Iraq, the top spooks helped convince the world that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction when it turned out he had none. Few complained when Congress started carving the agency into pieces in late 2004. So with the spectacular coup in Abbottabad, it's fair to ask, Has the CIA turned itself around? Can the secret agency in suburban Virginia once more protect the country, while telling the truth about the threats it faces? In his first interview since running the operation that killed bin Laden, Panetta argued that his agency has earned the nation's trust again. "This place really does have a fundamental commitment to protecting the country," he said. "If you provide the right leadership and the right values, they're going to do one hell of a job." The Upside of Downsizing Not for the first time, the CIA has marched a long road back to self-respect. When Panetta, a former Congressman, Cabinet member and White House chief of staff, arrived at the agency in February 2009, the place resembled nothing so much as a whipped dog. It had been the favorite punching bag during the Bush years, blamed for its errors as well as the misjudgments of the political leaders to whom it answered.

- 38. Panetta's predecessor, General Michael Hayden, had tried to rebuild the agency's reputation on Capitol Hill, rolling back interrogation and detention programs that had brought accusations of torture and illegal activity, focusing instead on producing reliable, actionable intelligence. But "the relationship with Congress had gone to hell," Panetta says, and the agency was gun-shy. "Every time they went up on the Hill, they got the hell kicked out of them, and they became very defensive." It helped that the CIA was much diminished. Acting on the recommendation of the 9/11 commission, Congress stripped the CIA of much of its power over sister agencies like the National Security Agency and the 11 other members of the U.S. "intelligence community" in 2004. Whereas once the CIA chief determined the budgets of the other agencies and safeguarded CIA supremacy in intelligence operations abroad and intelligence analysis at home, by 2006 it was merely one agency among many competing for the attention of policymakers. The CIA fought the restructuring and lost. But current and past senior CIA officials say the downsizing has turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Instead of wasting time worrying about the budget for the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, CIA leaders were able to concentrate on their core mission of collecting and analyzing intelligence for policymakers. "Removing the managerial stuff has made them leaner and more muscular," says former acting director John McLaughlin. It "has freed the agency to focus intensely on a lot of other things." And, apparently, double-check its work. Panetta says the bin Laden mission is a good example of that. On April 26, he held a final briefing on the Abbottabad compound in his office that included 15 team leaders from the CIA CounterTerrorism Center, some from the special-activities division (which runs covert operations) and some from the office of South Asian analysis. Panetta wanted to get their final opinion of the coming mission. Support was not unanimous, and there were ghosts in the room: some of the officers had been involved in the Carter Administration effort to go after the hostages held by the Iranians; others had been involved in the ill-fated raid against Somali warlords in 1993. Some officials, Panetta says, worried, "What if you go down and you're in a firefight and the Pakistanis show up and start firing? How do you fight your way out?" But he says the agency had second- and third-guessed the problem, arranging for backups and double-backups in the event of snafus. "We'd red-teamed that issue to death," he says. The biggest change at Langley may be Panetta himself. The boss pushed the spooks much harder than some of their previous leaders had to share information with lawmakers on Capitol Hill in order to build trust — and free up cash for vital missions in return. But Panetta also surprised agency veterans by pushing back when Attorney General Eric Holder Jr. launched an investigation into the destruction by the CIA's top clandestine official, Jose Rodriguez, of videotapes containing interrogations of al-Qaeda leaders. That earned Panetta high marks inside the building, observers say. Though he lost the battle, he helped limit the scope of Holder's investigation. He also fought a fierce battle over turf with Dennis Blair, the former director of National Intelligence, who wanted to decide who would be in charge of gathering intelligence at foreign posts. Panetta contested the release of the legal memos that justified "enhanced interrogation techniques" like waterboarding. President Obama, Holder and Panetta say waterboarding constitutes torture; Rodriguez

- 39. tells TIME that enhanced interrogation techniques provided "the lead information that eventually led to the location of [bin Laden's] compound." Rodriguez says Panetta "has done a fantastic job." Panetta insists his approach is just common sense. "I said, Look, the key here is to tell the Congress what's going on and to be very up-front about what we're doing, because in the end, if you do that, they may not always like what you're doing, but at least they know that you're being honest with them." Panetta moves to the Pentagon on July 1 and will be replaced at the CIA by General David Petraeus, who has spent the past decade, on and off, fighting overt and covert wars in South Asia. He watched the mission in Abbottabad from his seventh-floor conference room at CIA headquarters, which had been repurposed into an operations center. The hardest part was waiting to hear that bin Laden was there. When special-ops chief William McRaven finally said they had "Geronimo," using the code word to confirm that bin Laden was in the compound, there was an audible sigh of relief. But it was only when the helicopter took off from the compound with the Seal team and bin Laden's body on board that Panetta's office broke into applause. The director then went to the White House at 6:30 to oversee and report on the formal identification of bin Laden's body and wrapped up meetings an hour after the President made his announcement of bin Laden's death to the country. As he left the White House, he could hear the crowds in Lafayette Square cheering and waving flags. One chant, he says, was "CIA! CIA!" "We've really turned a corner," the spymaster said to himself. How Can We Trust Them? By ARYN BAKER Friday, May 20, 2011 Pakistanis gather for prayer at the Data Darbar Sufi shrine in Lahore Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images for TIME

- 40. The resort town of Abbottabad is a familiar one to day-tripping Pakistanis seeking escape from the urban tumult of the Punjab plain. Just 75 miles (120 km) from the capital, Islamabad, colonial-era bungalows abut modern whitewashed villas on small streets largely devoid of traffic. It's the kind of place where families take a stroll as the day cools into night, where you might still go and ask a neighbor for a cup of sugar. So when residents learned that Osama bin Laden had been living there, possibly for several years, they were shocked. Much less understandable is the claim, being made by defensive officials in Islamabad, that no one else in Pakistan was aware that bin Laden was in Abbottabad. That the world's best-known terrorist could be hiding in plain sight may be plausible in a country where privacy is a sacred right. But in Pakistan, household secrets rarely stay that way. Housekeepers and servants gossip at the back doors, and drivers chuckle over the infidelities of their employers. Anything that raises more than an eyebrow is quickly brought to the attention of "the agencies" — local parlance for Pakistan's ubiquitous intelligence groups, which closely monitor the daily lives of citizens, as much in an effort to collect information as to enforce a paranoia-driven code of good behavior. As any foreigner living in Pakistan knows, "the agencies" are especially adept at ferreting out the presence of strangers. The crackle and click of telephone lines is a constant reminder that no conversation is private, the crew-cut men in beige who materialize at inopportune moments proof that one is never quite alone in Pakistan. So it beggars belief that absolutely no one knew who was living in a compound that was, according to a U.S. official, "custom-built to hide someone of significance." John Brennan, President Obama's adviser on counterterrorism, didn't arch his eyebrows when he declined at a May 2 press conference to "speculate about who [within the Pakistani leadership] had foreknowledge about bin Laden being in Abbottabad." But his skepticism was palpable. The location of bin Laden's last address "there, outside of the capital, raises questions," Brennan said. Those questions are at the heart of the renewed debate about one of the U.S.'s oldest partners in the battle against terrorism. It can be summed up quite simply: Can Pakistan be trusted? If not, what can the Obama Administration, so keen to extricate U.S. troops from the region, do about it? And just how safe is Pakistan now that bin Laden is gone? The answers are not reassuring. Bin Laden was not the cause of Pakistan's problems. But his presence in Abbottabad was a symptom of a deeply ambivalent official approach to militancy that threatens to undermine the stability of this nuclear-armed state. Elements in the Pakistani military have long viewed militants and extremists as useful proxies. A blinkered focus on a perceived threat from the old enemy, India — with which Pakistan has fought three wars over the disputed territory of Kashmir — has led to massive military spending, depriving generations of Pakistanis of good education, adequate health care and the basic building blocks of an economy — electricity, irrigation, roads. Then there's the sheer corruption and incompetence of most Pakistani institutions: the leadership, both civilian and military, has pursued power at the expense of building a functional political apparatus that promotes accountability over cronyism and punishes inefficiency. Even as Pakistan attempts to function, it is racked by insurgencies — one in the western province of Baluchistan, where residents are demanding a share of the oil and gas wealth coming from their lands,