CM9

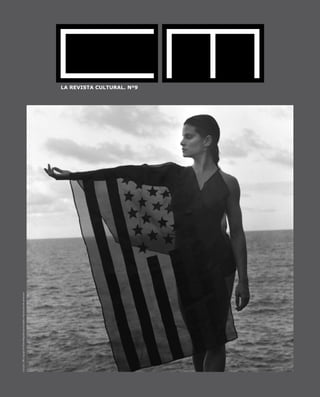

- 1. LA REVISTA CULTURAL. Nº9 LisaLyon,1982copyright©RobertMapplethorpeFoundation.Reproducedwithpermission

- 2. Acceso gratuito al centro y a las exposiciones Plaza de Weyler, 3 · Tel. 971 178 500 · www.laCaixa.es/ObraSocial Hasta el 10 de mayo

- 3. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 3 CM - Cultura Mallorca Fotografía: Tom Solo (portada), Patrick Parenteau, Brigitte Lucke, Victor Castells Avinyó Traducción: Judith Glueck Supervisión: Santiago Fabré de Balanzo, Christiane Nolte Colaboración: Aina Riera, Marga Melià, Josef Kiffmeyer, Teresa Ruiz de Apodaca, Michael Mittau, Santiago Stonelli Reservados todos los derechos, prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de los artículos, fotografías, ilustraciones y demas contenidos, sin permiso previo del editor. CM no se hace responsable de las opiniones de sus colaboradores ni se identifica con las mismas. Impressum: Dr. Brigitte Lucke – Editor Arquitecte Benassar 67 07004 Palma de Mallorca Tel. +34 971 20 60 47 • +637 516 492 info@culturamallorca.com www.culturamallorca.com Marketing Mallorca: Aina Riera 610 643463 Marketing Barcelona: Marga Melià Rigo 606091629 Webdesign: Michael Mittau Tel. +49 211 1588310 www.tech-nomades.de Diseño y maquetación: Anibal Guirado / Ramón Giner Tel. + 34 971 711559 / + 34 971 723172 ramon@gdos.net Impresión: BIG. Bahía Indústria Gràfica Deposito Legal: PM-2696-2006 METAPAISAJES Texto: Pau Waelder. Fotos: Fundación Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca BOTERO: UNA MIRADA DIFERENTE MARIO ELEFANTHELIADIS: EL PECADO SALVA BERNAT SANSÓ: OBRAS 1997-2007-09-11 Texto y fotos: Solleric ART AL CARRER: MANOLO VALDÈS A PALMA Texto: CAIXA-FORUM. Fotos: Patrick Parenteau …Y AL FINAL FUE MERZ Texto: Pilar Ribal / Foto: Patrick Parenteau DESPUÉS DE ERROR ENTREVISTA CON AMPARO SARD Texto: Aina Riera. Fotos: red. NACHO FRISUELOS: DE LA PINTURA COMO PAISAJE INFINITO Texto: Pilar Ribal. Fotos: Tom Solo LA DESCONSTRUCCIÓN DE LO COTIDIANO Texto: Marga Melia AGENDA LOCAL ARTISTA INVITADO: NACHO FRISUELOS / Foto: Tom Solo CUANDO LAS OBRAS SALEN DEL ESTUDIO SIENTO SU PERDIDA BIEL AMER EN CONVERSACIÓN CON PEP LLAMBIAS Fotos: red. SIN PIE DE PAGINA PINTORA Y GALERISA: MIQUELA NICOLAU Texto: red. Fotos: Victor Castells Avinyó CA N’ALLUNY: LA CASA DE ROBERT GRAVES Texto: Ca n’Alluny. Fotos: Patrick Parenteau STRUKTUR VISIONEN 07 SCHÜNO Texto: Red. Foto: Schüno AGENDA NACIONAL AGENDA INTERNACIONAL UN VERANO EN EL CINE Texto y fotos: Marga Melia EL ARTESANO DE LA NUEVA GASTRONOMÍA VICENTE FORTEA Texto: Teresa Ruiz de Apodaca RUTES SENDERISTES A MALLORCA: REFUGIS DE LA MUNTANYA Text i fotos: Jona Ramon Bosch Cerd LA ÚLTIMA PÁGINA: FOTOGRAFO INVITADO: PATRICK PARENTEAU (Vancouver) 6 10 12 14 16 18 21 22 24 26 28 30 32 35 36 38 40 42 44 47

- 4. MANEU BAHIA

- 5. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 5 CM , una revista independiente y trilingüe, se presenta desde hace más de tres años en España y Alemania, Suiza, Inglaterra, Irlanda, Estados Unidos, Canadá, Nueva Ze- landa y Hong Kong como un referente en la divulgación de la cultura contemporánea, con el objetivo de conectar con las vibraciones culturales más emergentes e intere- santes como de crear un vinculo entre los procesos creativos de múltiples artistas con nuestros lectores. En una amplia distribución en galerías, museos, fundaciones y ferias internacionales de arte contemporáneo, CM trabaja desde la aparente sencillez del blanco y negro para hacerte llegar las últimas reflexiones del panorama cultural. Con nombres como Mapplethorpe, Miroslav Tichy o Takashi Murakami os presenta- mos en este nuevo número las últimas exposiciones con críticas de arte, reflexiones y artículos que estamos seguros de que serán de vuestro interés. Así como los artistas invitados en esta nueva edición son los mallorquines Rafel Morey y Mónica Fuster. CM quisiera tener un feedback positivo con todos vosotros, para ir creciendo en base a vuestras críticas constructivas, por ese motivo, CM cuenta con un forum especializado en cultura accesible a través de nuestra pagina web: www.culturamallorca.com Quisiéramos aprovechar la ocasión para comentar nuestra grata sorpresa al en- terarnos de que CM tiene grandes seguidores que coleccionan los números an- teriores, que, o ya tienen la colección entera de la revista o nos van pidiendo algunos números para irla completando. Por último quisiéramos agradecer a todos nuestros lectores que desde un principio han compartido este nuevo reto editorial, el seguimiento que han hecho de la revista como las demostraciones de apoyo. Gracias por creer en la única revista especializada en arte contemporáneo de Baleares, que poco a poco irá rompiendo más y más barreras. Brigitte Lucke CM - Cultura Mallorca La revista cultural para Mallorca

- 6. 6 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 Cristina Ros Salvà All works copyright © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Qüestió de distànciesA question of distances

- 7. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 7 A Robert Mapplethorpe el miram amb els ulls de l’actualitat. Observar avui cadascuna de les seves fotografies, tot i conèixer la trajectòria vital i artística de qui ha restat com a mite de la revolució homosexual dels anys setanta i vuitanta als Estats Units, tot i que el sapiguem transgressor, provocador, amb un interès manifest per la celebritat, visionari pel que fa a l’art però també al mercat i, fins i tot, encara que el reconeguem en l’afirmació, realitzada per ell mateix, que era part de la cultura americana que li va ser contemporània, amb tot i això, les seves fotografies s’observen avui des de la distància que imposa el present. Els artistes i les obres són importants pel que significaren a la seva època, però també, tant o més, per la seva capacitat de suportar el pas de l’època, de les dècades, i fins i tot el pas de l’artista i de les seves revolucions. Les fotografies de Mapplethorpe, quan es compleixen dues dècades de la mort de l’artista, aguanten amb la mateixa força l’observació de l’actualitat. La distància que marca la caducitat dels calendaris no les ha engroguides. Més encara, una vegada que ha quedat enrere l’enrenou que produïren, quan ja no és possible interpretar-les com a crides d’atenció o com a camins marginals i escandalosos que havien de redundar en notorietat per a l’artista, els nus masculins, les escenes de sexe, els retrats o les llargues sèries de flors es defensen amb excel·lència per si mateixos. Salvada la distància entre l’actualitat i l’ahir de les obres, Mapplethorpe mateix en va marcar moltes altres, de distàncies, algunes més notòries que no d’altres. Millor dit, algunes han quedat escrites a la seva biografia i d’altres es poden llegir amb força claredat a les seves fotografies. No és el propòsit d’aquest article breu aprofundir en la biografia de l’artista, ni tan sols fer-ne una crònica de passada, tot i que fos per esmentar la distància establerta entre el camí emprès i l’educació tradicional i catòlica rebuda o, fins i tot, la distància, i més que distància, el trencament amb tants de prejudicis que respecte del sexe, la raça, el gènere o la religió mateixa hi havia tan sols fa trenta o quaranta anys. Cal destacar, això sí, la tasca de qui fou un esteta, un artista amb una enorme preocupació estètica, un home amb l’objectiu ferm d’anar a la recerca de la bellesa que emana o que es pot descobrir en els cossos animats i inanimats. Així que la distància és obligada si es persegueix la perfecció, per molt que l’artista s’apropàs als models, convisqués amb bona part d’ells o hi tengués relacions íntimes. El control de la imatge fins a l’obsessió per la perfecció tècnica i/o la de qualsevol dels elements i detalls que intervenen a l’obra l’obliga a allunyar-se de l’objecte, sia aquest un tros de pa, sia un gerro amb una flor, sia un penis, un tors, un home o una dona. No es tracta d’una distància física, sinó d’una distància psicològica, una manera de mirar des de fora, per poder analitzar, calcular i controlar. Robert Mapplethorpe ho deia i ho repetia, que ell no deixava res a l’atzar. El fotògraf, eminentment fotògraf d’estudi, semblava trobar-se bé sobretot a l’espai i amb les persones i els objectes que ell podia dominar des del principi a la fi. També amb els processos, tot i la investigació. Controlava al mil·límetre les composicions, les proporcions, els equilibris, els enfocaments, el blanc i negre, les ombres i la llum, les postures dels cossos, les actituds, les textures de les pells, el color quan el va fer servir, tot allò que havia d’entrar en We view Robert Mapplethorpe through the eyes of the present. Even though one is aware of the biography and art of a mythical figure in the gay revolution of the 1970s and 80s in the US, even though one knows him to have been transgressive, provocative, markedly interested in celebrity, a visionary with respect to art but also with respect to the market, and even though one recognises him in the statement he made about himself - that he was a part of his own contemporary American culture – still, his photographs are viewed today from the distance imposed by the present. Artists and works are important for what they mean in their day, but also, as much or more so, by their capacity to bear the passing of that day, of decades and even of the artist and his revolutions. Two decades after Mapplethorpe’s death, his photographs can still bear today’s gaze with the same forcefulness. The distance that marks the lapsing of calen- dars has not aged them. What’s more, the noise they produced has all been left behind, now that it is no longer possible to interpret his works as attention-seeking or marginal and scandalous pathways intended to make the artist notorious; the male nudes, the sex scenes, the portraits or long series of flowers are defences in themselves par excellence. Aside from the distance between the yesterday and today of his works, Mapplethorpe him- self marked many other distances, some more famous than others. Some have remained

- 8. 8 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 la fotografia i tot el que hi havia de quedar a fora. Perseguia la perfecció fins a l’eliminació dels defectes. I tot aquest control és fruit d’una distància que l’artista s’havia d’imposar respecte de la pròpia obra. Més enllà del sexe, de la raça i del gènere, el cos humà es torna, d’aquesta manera, pura forma, una forma eminentment bella quan passa per l’ull de Mapplethorpe, que a més tenia ull per triar cossos extraordinaris. El mateix passa amb les orquídies, els lliris xinesos o les tulipes, que es retorcen, es tanquen o s’obren insinuants, com si fossin cossos, formes belles i, per tant, igualment desbordants d’erotisme. Figures animades que es converteixen en figures inanimades del tot sotmeses a l’artista. Es converteixen en escultures, molt més suggerents per la forma que no perquè l’artista intenti extreure el foc de cap ànima que hi pogués habitar a dintre. Contràriament, quan fotografia estàtues, en una reconeguda sèrie, sembla perseguir-ne l’expressió, com si volgués animar aquelles figures clàssiques de marbre o bronze i convertir-les en éssers dotats de a part of his written biography and others can be very clearly read in his photographs. This brief article does not intend to delve into the artist’s biography, not even to suc- cinctly chronicle it, although it must men- tion the distance between the path he took and the traditional, Catholic education he received and even the distance - or rupture rather than distance - from the many preju- dices about sex, race, gender and religion itself that existed only thirty or forty years ago. Yet, it does indeed propose to highlight the work of a man who was an aesthete, an artist with an enormous aesthetic sense, a man with an unyielding goal: to seek the beauty that emanates or can be discovered in animate and inanimate bodies. So distance is obligatory when one pur- sues perfection and this is true no mat- ter how close the artist gets to his mod- els, no matter whether he lives with or maintains intimate relations with a good many of them. Controlling an image to the point of obsessing over technical per- fection and/or any element or detail that intervenes in a work forces an artist to distance himself from the object, be it a chunk of bread, a vase with a flower, a penis, a torso, a man or a woman. This is not a physical, but rather a psycho- logical distance, a way of looking at the object from the outside so as to be able to analyse, calculate and control it. Rob- ert Mapplethorpe said it on many occa- sions: he left nothing to chance. An emi- nently studio photographer, he seemed to be comfortable in a space and with people and objects he could dominate from start to finish; beyond the research he conducted, the same thing was true of his processes. He controlled down to the millimetre his compositions, propor- tions, balances, approaches, blacks and whites, lights and shadows, positions of bodies, focuses, skin textures, colour when he used it - everything that was al- lowed to come into the photograph and everything that remained outside. He pursued perfection until all flaws were removed. And all this control was the fruit of a distance from the work itself that the artist was forced to impose upon himself. After passing through Mapplethorpe’s eye, which was also adept at choosing extraor- dinary bodies, the human body thus became pure, an eminently beautiful shape beyond sex, race or gender. The same thing can be said about the orchids, Chinese lilies and tulips that twist, close or open insinuatingly, as if they were bodies, beautiful shapes that are therefore equally overflowing with eroticism. Animated figures that become inanimate and absolutely submissive to the artist’s will. They become sculp- tures, much more suggestive because of their shapes than because of the artist’s attempts to extract the fire of a soul that may dwell within. To the contrary, when he was photographing statues in an acclaimed series, Mapplethorpe seemed to pursue their expression, as if he wanted to animate those classic marble and bronze figures

- 9. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 9 vida i sentiments, tots aquells sentiments que, moltes vegades, no trobam a les fotografies realitzades als seus amics, amigues i amants. Fotògraf de temes clàssics i a la recerca de la perfecció, revolucionari en el context sociopolític que li va tocar viure, Mapplethorpe, per la seva manera de mirar i d’interpretar les formes i, entre altres aspectes, també per fer a través del conjunt de la seva obra una mena de diari de les pròpies vivències i reivindicacions, és un dels grans precursors de la fotografia artística que domina la proposta contemporània. Vist des de la distància que ofereix el pas de dues dècades després de la seva mort, el 9 de març de 1989, l’obra de Robert Mapplethorpe esdevé encara més forta. and turn them living, feeling beings, endowed with all the feelings that are lacking on many occasions in the photographs taken of his friends and lovers. Photographer of classic themes in search of perfection, revolutionary within the socio- political context of his day, Mapplethorpe’s way of viewing and interpreting shapes and making a kind of diary of his own experiences and demands through his oeuvre made him one of the great precursors of the contemporary art photography scene. Viewed from the distance offered by the passing of two decades after his death on March 9, 1989, Robert Mapplethorpe’s work is now even stronger.

- 10. 10 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 An exhibition with works by Anselm Kiefer always poses a very special challenge to the observer, the curator and naturally, the collector as well. The artist’s works display such a wide variety in terms of the interpretation of the world and the depiction of the inconceivable, of the paradox, replete with illustrative metaphors and allegorical worldly landscapes, that approaching and contemplating them must be understood as a provocation to knowledge itself and one’s own capacity for perception - all this within a context with an impressive dimension and an aesthetic indelibly stamped on the ob- server’s view through a symbiosis between materiality and painting. Thus, Kiefer’s work is an on-going challenge to the senses and the spirit. Yes, we recognise everything we see, yet does that mean we have already grasped it? When collector Hans Grothe became familiar with Anselm Kiefer’s works in the mid- 1980s, he could not resist them and began to devote himself to them with the cor- responding consequences. He has compiled a considerable collection of twenty-five works from the score of years that stretch from 1989 to today. At first, the collector Una exposició amb obres d’Anselm Kiefer sempre és un desafiament molt especial, per a l’observador, el curador i naturalment també per al col·leccionista. Les obres de l’artista presenten tanta varietat quant a la interpretació del món i la plasmació de l’inconcebible, de la paradoxa, ple de metàfores il·lustratives i paisatges al·legòrics del món, que s’ha de comprendre l’aproximació i contemplació de l’obra com a provocació del propi saber i de la pròpia capacitat de percepció. Tot això dins el context d’una dimensió impressionant i una estètica, que es grava de forma inoblidable dins la visió de l’observador, mitjançant una simbiosi entre materialitat i pintura. L’obra de Kiefer és d’aquesta manera el continu desafiament dels sentits i de l’esperit. Sí que reconeixem tot allò que veiem, però vol dir que per això ja ho comprenem? El col·leccionista Hans Grothe no s’hi va poder resistir, quan a mitjans dels anys 80 va conèixer les obres d’Anselm Kiefer i va començar a dedicar-se a elles, amb les conseqüències corresponents. Es va reunir una col·lecció considerable d’unes 25 obres dels vint anys que van de 1989 a avui. El col·leccionista al primer intent no va comprendre Anselm Kiefer Walter Smerling. President de la Fundació per a l’Art i la Cultura Fotos: Es Baluard

- 11. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 11 did not understand the early paintings, the origin of the Grothe collection, Lilith and The Big Freight. Yet, his fascination was so great that he wished to comprehend them and finally acquired them. This phenomenon has accompanied Grothe until today: “I identify what I see, although I do not understand it, and interpret it in a direction dif- ferent from the one Kiefer insinuates.” This, together with his fascination for Kiefer’s painting, as opposed to Keifer’s oeuvre as a whole, has captivated Grothe and is the only explanation behind the collector’s motives for separating himself from a large part of his complete and considerable collection of German contemporary art, with exception of Anselm Kiefer’s work, in mid-2005. Unlike the widely-held opinion that Kiefer is first a German painter who devotes himself primarily to German history, the Grothe Collection provides a different view. Grothe began to collect Kiefer when the latter was taking his leave of Germany, significantly through the work Census in the Magiciens de les terres exhibition. Sixty million peas, strung up and incrusted in lead strips and placed in an ordinary, everyday container oc- cupied by the monster Leviathan, which symbolised an entire nation’s political stance - paradoxical, disquieting and alarming all at the same time. This confrontation would be decisive in the German collector from Duisburg’s subsequent actions. Upon observing the selection in Es Baluard, it can be seen that overcoming Germany’s past, although exhibited in a particular form, does not represent the centre of Kiefer’s attention. Le voyage au bout de la nuit, Schwarze Flocken [Black Flakes], Die Grosse Fracht [The Big Freight], Shevirat HaKelim [The Breaking of the Vessels] and the stel- lar paintings For Robert Fludd: the Secret Life of Plants are testimonies to the poetic and philosophical culture of the work by this German artist who has settled in France. The twenty works on display at Es Baluard were largely produced outside of Germany, concretely in the southern French town of Barjac and in Paris. Perhaps that is why the works convey a new view of the complexity of artistic thought and action. Moreover, the pathos in Kiefer’s work, described on numerous occasions, appears strangely truncated, withdrawn and neutralised. The collection makes an impression without overpowering the spectators and invites them to an analytical reflection. To a large degree, Kiefer’s work reflects that which is extraordinarily important to the artistic and intellectual debate in Europe and many other parts of the world. els primers quadres, l’origen de la col·lecció Grothe, Lilith i Gran carregament. Això no obstant, va quedar tan fascinat que els volia comprendre i finalment els va comprar. Es tracta d’un fenomen que acompanya el col·leccionista fins avui: “Identific allò que veig, encara que no ho comprenc i que ho interpret en una altra direcció que la insinuada per Kiefer.” Aquest fet, juntament amb la fascinació per la pintura de Kiefer, captiven Grothe de cara a la obra global de Kiefer. És l’única explicació de perquè el col·leccionista a mitjans de l’any 2005 es va separar de gran part de la seva col·lecció completa i considerable d’art contemporani alemany, a excepció de les obres d’Anselm Kiefer. A diferència de l’opinió habitual de què Kiefer sigui en primer lloc un pintor alemany que es dedica principalment a la història alemanya, la col·lecció Grothe proporciona una visió diferent. Grothe va començar la col·lecció Kiefer, quan aquest s’estava acomiadant d’Alemanya, de forma significativa mitjançant l’obra Cens nacional a l’exposició Magieciens de les terres. 60 milions de pèsols, enfilats i incrustats dins tires de plom, ficades dins un contenidor normal i corrent, ocupat pel monstre Leviatan, simbolitzant la postura política de tota una nació. Va ser paradoxal, inquietant i alarmant a la vegada. Per al col·leccionista alemany de Duisburg, aquesta confrontació seria decisiva per a la seva actuació posterior. A l’hora d’observar la seva selecció a Es Baluard, es pot contemplar que per a Kiefer la superació del passat alemany, encara que exposat de forma característica, no representa el centre de la seva atenció. Dominen més bé els temes del cristianisme jueu, temes mitològics i polítics. Le voyage au bout de la nuit, Flocs negres, Gran carregament, She berat Hakelim i els quadres estel·lars Secret life of plants for Robert Fludd, són testimonis de la cultura poètica i filosòfica dins l’obra de l’artista alemany establert a França. Les 20 obres mostrades a Es Baluard són en gran part produïdes fora d’Alemanya, concretament al poble del sud de França Barjac i a París. Tal vegada per aquest motiu les obres transmeten una nova visió de la complexitat de l’acció i el pensament artístic. A més, el pathos dins les obres de Kiefer, descrit en nombroses ocasions, apareix estranyament trencat, replegat i neutralitzat. La col·lecció impressiona sense apoderar-se de l’observador i convida a una reflexió analítica. Les obres de Kiefer reflecteixen en gran mesura allò que per a la discussió artística i intel·lectual, a Europa i a moltes altres parts del món, té una importància extraordinària

- 12. 12 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 Las palabras de un rebelde e inconformista quien ha sido confrontado con una fama repentina a la edad de 79 años, cuando su trabajo fue exhibido por primera vez en “Kusthaus Zürich” en el 2005 y celebrado en el Centro Jorge Pompidou en una gran retrospectiva en el 2008; una fama que nunca buscó y que no le importa para nada. La biografía de Miroslaw Tichy esta en la línea de la carrera de muchos artistas en países pertenecientes al Pacto de Varsovia. Nacido en Checoslovaquia en 1926, cuando era niño demostró un inmenso interés por el dibujo y se convirtió en estudiante de la Academia de las Artes en Praga. Pasó años en prisión y en hospitales mentales y durante décadas vivió retraído y aislado en su pueblo natal de Kyiov. Allí encontró su nicho, viviendo como un paria, como alguien que no pertenece a ningún lugar, permitiéndole una cierta libertad y una vida autodeterminada. Él observó el mundo que le rodeaba a través de las lentes de sus cámaras caseras; un mundo, que él cree ser sólo una idea, que sólo existe tan allá como lo percibimos. Durante cuatro décadas caminaba por las mismas calles y alrededor de los mismos lugares, equipado con su cámara, que casi siempre escondía bajo su jersey. Tomó cientos de fotos cada día, revelándolas más tarde en su humilde estudio y colgando los negativos a secar en su patio trasero. La mayoría de sus fotos son imágenes de mujeres un tanto fuera de foco. Son muy atractivas y a primera vista parecen ser del siglo 19; no del siglo 20. Y es este sentido atemporal y esta falta de perfección que hacen que las imágenes parezcan poéticas y bastante místicas. Son como el largo diario de una persona que siempre se mantuvo al borde de la escena; sin nunca interactuar. A veces podemos ver una mirada, o una sonrisa o hasta un adiós con la mano; la mayoría de sus imágenes son tomadas desde una posición de observación, desde un lugar escondido. La característica esencial de su obra no es la perfección o documentación, sino su respeto y profundo amor por las mujeres como seres humanos preciosos; aunque él mismo lo rechazaría. Tal vez, dentro de esta actitud de escepticismo convencido, este impulso lo mantuvo vivo. The words of a rebel and non-conformist who has been confronted with sudden fame at the age of 79 when his work was shown for the first time in “Kusthaus Zürich” in 2005 and celebrated at the George Pompidou Centre in a large retro- spective in 2008; a fame he was never looking for and doesn’t care about at all. Miroslaw Tichy’s biography reads like many artists’ careers in countries belong- ing to the former Warsaw Pact. Born in Czechoslovakia in 1926 he showed an immense interest in drawing as a child and became a student at the Academy of Arts, in Prague. He spent years in prison and mental hospitals and lived for decades withdrawn and isolated in his hometown of Kyiov. There he found his niche living as an outcast, as someone who belongs to no- where, allowing him a certain kind of freedom and a self-determined life. He observed the world that surrounded him through the lenses of his homemade cameras; a world, that he believes to be only an idea, that only exists so far as we perceive it. For four decades he was walking the same streets and around the same places, equipped with his camera, which he mostly hid under his jersey. He took hun- dreds of photos each day, developed them later at his modest studio and hung the negatives in his backyard to dry. Most of his photos are slightly out of focus images of women. They are very ap- pealing and at first glance look to be from the 19th; not the 20th century. And it is this timelessness and lack of perfection that makes the images appear poetic and rather mystical. They read like the long diary of a person who always kept on the border of the scene; without ever interacting. Sometimes we can see an eye contact, a smile or even a wave; most of his images are taken out of an observing position, from a hidden place. The essential characteristic of his work is not in perfection or documentation, but his respect and deep love of women as beautiful human beings; even if he himself would reject this. Maybe, within this attitude of convinced scepticism, this impulse kept him alive. Miroslav Tichy “Si quieres ser famoso, tienes que ser el peor en algo que nadie más en el mundo” Miroslav Tichy “If you want to be famous, you have to be worse at something than everyone else in the world” Miroslav Tichy ??????????????????? Cortesia: Roman Buxbaum 2006, Mirislav Tichy , Tazan Retired. Film by Roman Buxbaum

- 13. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 13

- 14. 14 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 “Soy un abservador. “ “I am an observer.” “Todo cuanto existe es el mundo! Y cuando una parte de ella se volvió reco- nocible lo imprimí.” “Everything that exists is the world! And if some of it be- came recognizable, I printed it.” “Reconocemos únicamente aquello que podemos, y queremos reconocer.” “We recognize only which we can and want to recognize.” “De todas formas, el mundo no es más que una aparencia, una illusion.” “The world is anyway nothing but an appearance, an illusion.” “Todo lo decide la tierra, que está girando.” “Everything is decided by the earth which is turning.” “Las imperfecciónes forman parte de ella. Esa es la poesía.” “The flaws arte part of it.That’s the poetry.” “La fotografía es percepción. Los ojos – aquello que ves. Y ocurre tan de prisa. !I que a lo major no ves absolutamente nada!” “Photography is perception. The eyes, you see with. And it happens so fast that you may not see anything at all.”

- 15. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 15 “La fotografía significa pintar con la luz.” “Photography means painting with light.” “Nunca he hecho más que dejar que el tiempo pase. Voy al pueblo y debo hacer algo más que solo dar un paseo. Así simplemente apretaba el botón.” “I have never done anything beyond letting time pass by. I go to town and must do something, rather than just talk a walk. So I was simply pressing the release.” “La fotografía es una cosa concreta.” “Photography is something concrete.” Yo no seleccioné nada. Examiné el material bajo la ampliadora. Y todo lo que me parecía en algo al mundo, lo imprimí.” “I did not select anything. I looked at the stuff under the enlarger, and whatever seem to bear resemblance of the word, I printed.”

- 16. 16 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 SOLLERIC

- 17. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 17 Cadàver exquisit (Exquisite corpse) is a display proposal that integrates artists from different generations and very different styles. Exquisite corpse is a technique that allows a group of words or images to be put together as a group; the result is known as an exquisite corpse or cadavre exquis in French. Used by the surrealists around 1925, its inspiration comes from an old table game called “consequences”, in which the players wrote on a sheet of paper in turns, folded it to hide the writing and then they passed it on to the next player, for another collaboration. The name derives from a phrase that came up the first time it was played in French: Le cadavre / exquis / boira / le nouveau / vin (The corpse / exquisite / will drink / the new / wine). The theorists and promoters of this creative strategy (initially Robert Desnos, Paul Eluard, André Bretón and Tristan Tzara) postulated that creation, especially poetic or expressive creation, should be anonymous and collaborative, intuitive, spontaneous, recreational and, if possible, automatic. Eighty years later, cadavre exquis still preserves all its creative potential. For this reason, a creation of a new exquisite cadaver is proposed, with the collaboration of the following artists: Steve Afif, Josep Maria Alaminos, Amador, Rafael Amengual, Mateu Bauzà, Erwin Bechtold, Joan Bennàssar, Pere Bennàssar, Rafel Bestard, Jim Bird, Maria Carbonero, Maria Catalán, Pep Coll, Astrid Colomar, Joan Costa, Cristina Escape, Ñaco Fabré, Marian Femenías Moratinos, Paca Florit, Pep Guerrero, Gilbert Herreyns, Enric Irueste, Ellis Jacobson, Mercedes Laguens, Alícia Llabrés, Antoni Llabrés, Pep Llambías, Eugenio López, Joan March, Teresa Matas, Mariano Mayol, J.M. Menéndez Rojas, Maria Antònia Mir, Pepe Nebot, Ángel Pascual Rodrigo, Ra- fel Perelló, Cris Pink, Alceu Ribeiro, Enric Riera, Dolores Sampol, Lourdes Sampol, Àngel San Martín, Bernat Sansó, Horacio Sapere, Amparo Sard, Tòfol Sastre, Juan Segura, Joan Soler Rebassa, Andreu Terrades, Vicenç Torres, Rafel Tur Costa, Tomeu Ventayol and Amable Villarroel. The Cadàver exquisit exhibition – that has been in Ses Voltes from January 8 to Fe- bruary 8– is a coproduction that is part of the Projecte Llevant, thanks to which it has been possible for exhibitions of great quality to be carried out, and be presented in different exhibition halls in Majorca, Menorca and Ibiza. All the productions in this project have also been presented in Barcelona, and some of them in Bremen and Lüberg (Germany), in Moscow (Russia) and in Saragossa, amongst others. The Go- vernment of the Balearic Islands, the Consell de Mallorca, the Ajuntament de Palma and “Sa Nostra” Caixa de Balears have contributed to the now travelling exhibit. 53 artists for an “exquisite corpse” ?????????????????? Cadàver exquisit (Exquisite corpse) is a display proposal that integrates artists from diffe- rent generations and very different styles. Exquisite corpse is a technique that allows a group of words or images to be put together as a group; the result is known as an exquisite corpse or cadavre exquis in French. Used by the surrealists around 1925, its inspiration comes from an old table game called “consequences”, in which the players wrote on a sheet of paper in turns, folded it to hide the writing and then they passed it on to the next player, for another collaboration. The name derives from a phrase that came up the first time it was played in French: Le cadavre / exquis / boira / le nouveau / vin (The corpse / exquisite / will drink / the new / wine). The theorists and promoters of this creative strategy (initially Robert Desnos, Paul Eluard, André Bretón and Tristan Tzara) postulated that creation, especially poetic or expressi- ve creation, should be anonymous and collaborative, intuitive, spontaneous, recreational and, if possible, automatic. Eighty years later, cadavre exquis still preserves all its creative potential. For this reason, a creation of a new exquisite cadaver is proposed, with the collaboration of the following artists: Steve Afif, Josep Maria Alaminos, Amador, Rafael Amengual, Mateu Bauzà, Erwin Bechtold, Joan Bennàssar, Pere Bennàssar, Rafel Bestard, Jim Bird, Maria Carbonero, Maria Catalán, Pep Coll, Astrid Colomar, Joan Costa, Cristina Escape, Ñaco Fabré, Marian Femenías Moratinos, Paca Florit, Pep Guerrero, Gilbert Herreyns, Enric Irueste, Ellis Ja- cobson, Mercedes Laguens, Alícia Llabrés, Antoni Llabrés, Pep Llambías, Eugenio López, Joan March, Teresa Matas, Mariano Mayol, J.M. Menéndez Rojas, Maria Antònia Mir, Pepe Nebot, Ángel Pascual Rodrigo, Rafel Perelló, Cris Pink, Alceu Ribeiro, Enric Rie- ra, Dolores Sampol, Lourdes Sampol, Àngel San Martín, Bernat Sansó, Horacio Sapere, Amparo Sard, Tòfol Sastre, Juan Segura, Joan Soler Rebassa, Andreu Terrades, Vicenç Torres, Rafel Tur Costa, Tomeu Ventayol and Amable Villarroel. The Cadàver exquisit exhibition – that has been in Ses Voltes from January 8 to February 8– is a coproduction that is part of the Projecte Llevant, thanks to which it has been possi- ble for exhibitions of great quality to be carried out, and be presented in different exhibition halls in Majorca, Menorca and Ibiza. All the productions in this project have also been presented in Barcelona, and some of them in Bremen and Lüberg (Germany), in Moscow (Russia) and in Saragossa, amongst others. The Government of the Balearic Islands, the Consell de Mallorca, the Ajuntament de Palma and “Sa Nostra” Caixa de Balears have contributed to the now travelling exhibit. Part of the exhibition “Exquisite corpse”, with works by Astrid Colomar, Cris Pink, Alícia LLabrés, Joan March, Joan Ben- nàssar, Cristina Escape, Pep Guerrero and Amparo Sard. >>>>> (See photo second series corpse.jpg)

- 18. 18 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 La present exposició, amb caràcter retrospectiu i que romandrà en exhibició en la Planta Noble del Casal Solleric fins a finals de març, proposa una exhaustiva aproximació al treball de qui és considerant un dels noms essencials dins l’àmbit de l’escultura contemporània a les Illes Balears, i s’articula a partir de quatre nuclis te- màtics que inclouen obres de la seva etapa inicial, així com de les sèries Ferro-testes, Animals en acció i Homenatge a l’arquitectura, que en el seu conjunt permeten conèixer la seva evolució estilística. De formació autodidacta, Antoni Ferragut (Cartagena, Múrcia, 1946, i resident a Mallorca des del 1948) col·laborà en els seus inicis amb el Centre d’Investigacions i Activitats Artístiques de Xavier Corberó a Esplugues (Barcelona). Bona part de la seva producció pot ubicar-se dins l’àmbit de l’abstracció, encara que sovint s’hi de- tecten referències figuratives, algunes de caràcter zoomòrfic. El ferro s’ha configurat com un dels seus materials predilectes, i ha treballat també l’acer, el metacrilat, la fusta, el marbre i el bronze, entre d’altres. Són característiques les seves formes estilitzades i contundents, plenes de dinamisme, amb les quals aconsegueix acotar de manera sensual l’espai i el buit, presents sempre en el rere- fons conceptual de tota la seva obra. Ha realitzat obres en col·laboració amb importants arquitectes, alhora que cal des- tacar també la presència de les seves escultures monumentals a diferents indrets públics i privats de l’illa. El Casal Solleric revisa l’obra d’Antoni Ferragut ?????????????????? The present exhibition, with a retrospective character, that will be on display in the Planta Noble of the Casal Solleric until the end of March, proposes a thorough approximation to the work of who is considered one of the principal names in the field of contemporary sculpture in the Balearic Islands, and it focuses around four main themes, that include works from the first stages, as well as from the series Ferro-testes, Animals en acció i Homenatge a l’arquitectura, that as a whole show the evolution in his style. As a self-taught person, Antoni Ferragut (Cartagena, Murcia, 1946, and a re- sident in Mallorca since 1948) collaborated, in his first stages, with the Centre d’Investigacions i Activitats Artístiques de Xavier Corberó in Esplugues (Barcelona). Most of his work can be categorized under the area of abstraction, though often, figurative references can be detected, some of a zoomorphic character. Iron has become one of his favourite materials, and he has also worked with steel, methacrylate, wood, marble and bronze, amongst others. His stylized and blunt shapes, full of dynamism, through which he manages to delimit space and empti- ness, always present in the conceptual background of his work are typical. He has worked alongside important architects, and we must also point out the presence of his monumental sculptures in different public and private places on the island. Antoni Ferragut. Llevant, 1984 Ferro 50 x 45 x 35 cm (Fotografia Joan-Miquel Ferrà)

- 19. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 19 Germán Gómez (Gijón, 1972), guardonat amb el Premi Revela- ció PhotoEspaña’08 –dotat amb 10.000 euros i que reconeix el tre- ball d’un fotògraf espanyol, menor de 35 anys–, presenta fins el pròxim 5 d’abril la instal·lació titulada Con- denados a l’Espai Quatre del Casal Solleric. La crítica ha coincidit a destacar el treball de Germán Gó- mez com el d’un artista que extreu de la memòria individual les refe- rències que li permeten interpretar les seves incerteses, enyorances i contradiccions. La sèrie d’obres que sota el títol de Condenados presenta ara a Palma resumeix el marcat caràcter autobiogràfic de la seva obra. La seva trajectòria ha consolidat l’obra d’un creador obs- tinat a comunicar quelcom distint cada vegada sense deixar de ser recognoscible sempre. En conjunt, el projecte que ara pre- senta l’Espai Quatre del Casal So- lleric, Condenados, neix de l’estada del seu autor a la capital d’Itàlia, becat per l’Acadèmia d’Espanya a Roma, on es va proposar traslladar al discurs contemporani els personatges de l’Infern de la Capella Sixtina. De fet, l’ar- tista de Gijón va partir de la figura de Miquel Àngel per elaborar una paràbola entorn de determinades “ferides històriques” derivades de la identitat i les seves contradic- cions. Per a això “va aïllar” algunes de les figures dels frescs de la Capella Sixtina i posteriorment va fotografiar, amb les mateixes poses, persones que sofreixen en vida el rebuig social per ser “diferents”: ja sigui per la seva raça, orientació sexual, pensa- ment, malaltia, minusvalidesa... En paraules de Germán Gómez, aquesta mostra “vol ser un humil homenatge a tots els que neixen condemnats”. Des d’aquesta perspectiva, l’autor assumeix que la seva obra fotogràfica es nodreix de contradiccions i mitjançant aquesta sèrie –i altres com Fichados-Tatuados, Gale- ria Fernando Pradilla, Madrid, 2008– construeix un gran al·legat artístic, una aguda reflexió entorn del “rebuig” al llarg de la història, al mateix temps que continua amb el relat del seu treball, en gran mesura autobiogràfic, exhibint-lo en una sala sota terra –l’Espai Quatre–, la qual cosa converteix el muntatge en un nou i metafòric descens als inferns, on es posen de manifest postures inquietants en aquests rostres i figures que s’entrecreuen lluitant, debatent-se entre el cel i la terra, formant un gran bloc mai perfecte i sempre ferit, marcat, compost, dibuixat... La comissària de l’Espai Quatre, Neus Cortés, ha avançat els noms dels artistes que realitzaran instal·lacions en el petit soterrani del Casal Solleric aquest any, entre els cuals destaca el nom de Esther Ferrer, guardonada amb el Premi Nacio- nal d’Arts Plàstiques 2008. José Maldonado, José Ramón Amondarain i Sáncherz Castillo són els altres artistes seleccionats per a intervenir en el Espai Quatre al llarg d’aquest any. Germán Gómez, guardonat amb el Premi Revelació PhotoEspaña’08, exposa a l’Espai Quatre del Casal Solleric ?????????????????? Germán Gómez (Gijón, 1972), awarded the Revelation Prize in PhotoEspaña’08 - a prize of 10,000 euros and recognizing the work of a Spanish photographer less than 35 years of age - presents until next April 5th at Casal Solleric’s Espacio Cuatro an installation titled Condenados (Condemned). Critics have coincided in praising Germán Gómez’s work as that of an artist who can extract from an individual memory, the references that allow him to interpret his uncertainties, yearnings, and contradictions. The series of works presented now in Palma under the title, Condenados, summarizes the marked, autobio- graphical character of his work. His trajectory has consolidated the work of a creator tenaciously attempting to communicate something differ- ent each time while always remain- ing recognizable. As a collection, the project he now presents at Casal Solleric’s Espacio Cuatro, Condenados, is born out of the author’s stay in the capital of Italy, sponsored by the Spanish Academy in Rome, where he proposed translating the contemporary discourse of hell’s characters in the Sistine Chapel. In fact, the artist from Gijón stems from Michael An- gelo’s figure to elaborate a parable around certain “historical wounds” derived from the identity and its contradictions. For this he “isolated” some of the figures from the frescos in the Sistine Chapel and later photographed, with the same poses, people who suffer in their lives from social rejection for being “different”: be it for their race, sexual orientation, thoughts, illness, handicap… In the words of Germán Gómez, this show “wants to be a humble homage to all those who are born condemned”. From this perspective, the author assumes that his photographic work is nurtured by contradictions and through this series - and others like Fichados-Tatuados (Caught-Tat- tooed), Fernando Pradilla Gallery, Madrid, 2008 - he constructs a great artistic allegory, an acute reflection as to “rejection” throughout history, at the same time continuing his work’s story, in large part autobiographical, exhibiting it in an underground hall - Espa- cio Cuatro -, which turns his work into a new montage and a metaphorical descent into hell, where worrying postures in these faces and figures that are interlaced fighting are manifested, debating themselves between heaven and earth, forming a great block, never perfect and always wounded, marked, complex, drawn… Espacio Cuatro’s commissioner, Neus Cortés, has advanced some of the names of the artists that will be presenting their installations in the small basement of the Casal Solleric this year, of which the name of Esther Ferrer, awarded the National Visual Arts Prize 2008, stands out. José Maldonado, José Ramón Amondarain and Sáncherz Castillo are some of the other artists selected to take part in Espacio Cuatro throughout this year. Germán Gómez. CONDENADO RETRATO IX, 2008. Fotografia de color i fil, 100 x 100 cm, peça única.

- 20. 20 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 John Ulbricht, one of the most gifted painters in acquired culture in the world to- day, shows the head almost human in his portraits, but only the head, as the only home for homogeneousness, in order to evidence the Face of Time embodied and already personified. For Ulbricht, the technique of imagining Time in a significant manner, as a step and character of the Face, consists of identifying white Space’s material, barely clayey, with the material almost golden, desolate, from the characteristics that make up the mysterious biology of character. More specifically: a zone within the Space has concentrated and accumulated enough cosmic energy so that, from the comprehension and internalization of the material, the Face’s definitive John Ulbricht, uno de los pintores más dotados de cultura adquirida, que hoy existen en el mundo, en los retratos presenta la cabeza llegada a humana, pero sólo la cabeza, como único hogar de la hominización, para hacer evidente el Rostro del Tiempo encarnado y ya personal. La técnica para dar una significativa figuración del Tiempo, como paso y carácter del Rostro, consiste para Ulbricht en identificar la materia del Espacio blanco, ar- cilloso con lejanía, con la materia casi dorada, asolada, de los rasgos que arman el misterio biológico del carácter. Más concretamente: una zona del Espacio ha concentrado y acumulado suficiente energía cósmica para que, de la compren- sión e interiorización de la materia, naciera el Instante definitivo del Rostro, que JOHN ULBRICHT Extract from a Blai Bonet text

- 21. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 21 Instant could arise, reflecting and mirroring the warm colour of the lands of the Earth. The popular expression “the face of the earth” deeply defines the being in Ulbricht’s unrepeatable portraits. In some of those “facies” of Space, Picasso’s for example, they not only portray the head’s roundness and warmness, but the painting expresses the agitated biology and biography of temporality’s Face and life’s moons instilled in Picasso. In the continuation of that act of drawing cracks in the universe’s skin, which is the portrait of total Space and of personal Time, Ulbricht, in the last portraits and paintings of 1973, has found new elements to achieve the birthing of the Face of Space: in the portrait of the American author, friend to the poet Dylan Thomas, Ruthven Todd, the presentation of the biography and the character’s biography is carried out by two proper elements of individuality’s intra history portrayed, but that the author, in his eagerness to turn each frame into a unique work, makes present in the form of expressions external to the Face of Time: the darkening of the existential material of the individuality is thrown at Space’s whiteness, which is left greenish, blackened, earthy and muddied hominy. And the face was left this way, translucent, oxygen coloured, the hair portrayed in its reality of flaps of smoke with fog… And, instead of the Look, the glasses’ objectivity presented as dead nature, an optical still life about the Face which says “always tomorrow, and never do we morrow.” The portrait of an intellectual girl with our time’s fury at the ready, is the investitu- re of an arrested whirlwind, dark, greenish with brown areas, very visible stirring lines from the brush’s bristles, where the Space and the concentration of its matter in the head’s Time are a proper dark green fiery treatment. The darkened tongue and groove, not dark, of Space and of Time are here a compactness and almost union, only broken deliberately by the hanging threads, employed as a plastic part of the canvas, which threatened with bad weather, with storm… As in Ruthven Todd’s portrait, the strong accent was, is, in the still life of the glasses over the still living nature within the pale eyes, the deep portrait the girl is in the supreme find, delicate, tragic, of the pale, cyclamen coloured lips, which, within a few centimetres of high paint, synthesize and portray the small splendour, or minimized, of Time’s spring spectacles. Ulbricht’s incredible capacity to portray, to attract the visual reality of beings is, nevertheless, in the spacious painting, which is the musical theme’s Portrait, a great rectangular canvas, probing the whitest Space, one of the highest level whites I’ve seen in paint, being crossed by a counter position of intensities of cyclamen and amaranth coloured blooms, and of different situations of green in the leaves and of its different situations of green in the leaves and of its reverbe- rations, fugitives, like splinters over the whiteness, that express only pictorially what, in the musical theme, is the impressionist vibration of the concrete sound of each note. The impressive find, also impressionist in the mental sense of Manet, Mallar- mé, Debussy, is in that the Portrait of the musical theme has the Space in two versions, the Space over the space; the strict white, which vibrates above and below the monumental canvas, and the space of different times, attentions, me- lodies, twilights, of green, which, in regards to the cyclamen coloured densities of the musical theme, are the spatial orchestration, the orquestral colour, and the Colour that specializes in each instrument. The multiple collections of green, the vicinity of the situations of the sun’s greenishness, don’t retain any natural perspective in regards to the spectator. It is the perspective of the visual sounds of green, orquestrated over the base of the original whiteness. And this pictorial reason of which, neither on the whitened surfaces of the cloth’s superior and inferior parts, nor in the movement of green’s escapes and densities, is there any reverberation of the musical theme’s amaranth colour, which is Time’s portrait; the mentally whitened whiteness and the orquestration of the green are the Space of the perennial leaf and that always remains, like the sky and the earth. Like the unrepeatable Art Ulbricht man within the human species. refleja y espejea el cálido color de las tierras de la Tierra. La expresión popular “la faz de la tierra” define con hondura el ser de los retratos irrepetibles de Ulbricht. En alguna de esas “facies” del Espacio, la de Picasso, por ejemplo, además de retratar la rotundidad y el templaderal de la cabeza, el cuadro expresa la biología y la biografía agitadas del Rostro de la temporalidad y de las lunas de la vida instalada en Picasso. En la continuación de ese acto de hacer calas en la piel del universo, que es el retrato del Espacio total y del Tiempo personal, Ulbricht, en los últimos retratos y pintados en 1973, ha encontrado nuevos elementos para lograr la parición del Rostro del Espacio: en el retrato del escritor americano, amigo del poeta Dhylan Thomas, Ruthven Todd, la presentación de la biografía y de la biografía del per- sonaje está realizada por dos elementos propios de la intrahistoria de la indivi- dualidad retratada, pero que el pintor, en su ahínco de convertir cada cuadro en una obra única, hace presentes en forma de expresionaduras externas al Rostro del Tiempo: el oscurecimiento de la materia existencial de la individualidad es echada al blancor del Espacio, que queda verduzco, ennegrecido, terroso y limos de homonía. Y el rostro quedó así, traslúcido, de color de oxígeno, la cabellera retratada en su realidad de colgajos de humo con niebla… Y, en vez de la Mirada, la objetividad de las gafas presentadas como una naturaleza muerta, un bodegón de óptica sobre el Rostro que dice “siempre mañana, y nunca mañanamos”. El retrato de una muchacha intelectual con el furor en ristre de nuestra época, es la embestida de un torbellino arrestado, pardo, verduzco con amarronamientos, muy visibles los surcos en revolera de las cerdas de la brocha, donde el Espacio y la concentración de su materia en el Tiempo de la cabeza son una misma lum- brada de tramado verdinegro. El machihembrado oscurecido, no oscuro, del Es- pacio y del Tiempo son aquí una compacidad y una casi unicidad, sólo quebrada por las hilachas deliberadamente, empleadas como factor plástico del lienzo, que amenaza con mal Tiempo, con temporal… Como en el retrato de Ruthven Todd el acento fuerte estaba, está, en el bodegón de las gafas sobre la naturaleza viva aún de los ojos mortecinos, el ahondado retrato la muchacha está en el hallazgo supremo, delicado, trágico, de los pálidos labios de color ciclámen, que, en unos pocos centímetros de pintura alta, sintetizan y retratan el esplendor pequeño, o empequeñecido, de los espectáculos primaverales del Tiempo. La increíble capacidad de Ulbricht para retratar, atraer la visualidad real de los seres está, sin embargo, en la espaciosa pintura, que es el Retrato del tema musical, un gran lienzo rectangular, sonde el Espacio blanquísimo, unos de los blancolores más altos que he visto en la pintura, está siendo cruzado por una contraposición de intensidades de floraciones de color ciclamen, amaranto, y de diferentes situaciones del verdor en las hojas y de sus diferentes situaciones del verdor en las hojas y de sus reverberaciones, fugitivas, como esquirlas sobre la blancura, que expresan solo pictóricamente lo que, en el tema musical, es la vibración impresionista del sonido concreto de cada nota. El hallazgo impresionante, también impresionista en el sentido mental de Manet, Mallarmé, Debussy, está en que el Retraro del tema musical tiene el Espacio en dos versiones, el Espacio sobre el espacio; el blanco estricto, que vibra arriba y abajo del lienzo monumental, y el espacio de diferentes tiempos, vigilias, mediodías, crepús- culos, del verde, que , respecto al tema musical de las densidades de color ciclamen, son la orquestación espacial, el colorido orquestal y el Color que se especializa en cada instrumento. Los múltiples conjuntos de verde, la vecindad de los grupos de si- tuaciones del verdor del sol, no guardan ninguna perspectiva natural con respecto al espectador. Es la perspectiva de los sonidos visuales del verde, orquestado sobre la base del blancor originario. Y esta razón pictórica de que, ni en las superficies enlu- cidas de la parte superior e inferior de la tela, ni en el movimiento de las densidades y fugas del verde, haya ninguna reverberación del color amaranto del tema musical, que es el retrato del Tiempo; el blancor mentalemente enlucido y la orquestación del verde son el Espacio de hoja perenne y que siempre queda, como el cielo y la tierra. Como el irrepetible hombre del Arte Ulbricht entre las especies humanas…

- 22. 22 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 In an event-filled World that makes us perceive all variations of grey through to the darkest shade of black, the breath of fresh air that opening a window represents is something to be grateful for, even if it does not occur at the most opportune of times. Leaving insipid shades of grey behind and revelling in the brightness of colour is synonymous with one name: Pep Coll. Despite manuals’ dogmatic theories, providing that it represents an escape from every day routine, Coll seems to have an innate gift for combining innumerable colours when unites all the colours that a palette full of experiences and memories can offer. His daring cannot be denied. The most glaringly bright, often disturbing of co- lours are combined with gentle, relaxing shades, moving from the brush to the canvas or paper with skill and harmony. Half-moon-shaped elements, shapes that take us back to childhood playgrounds or the wall of a convent, primitive-shaped little houses, tangled up worms, zigzags that erotically scribble out a triangle, squares with climbing criss-crossing lines, En un mundo lleno de incidencias, que nos obligan a percibir el gris en todas sus tonalidades, hasta el negro más oscuro, se agradece el aire fresco que comporta abrir una ventana aún siendo a destiempo. El dejar atrás el gris insípido para saborear la vivacidad del color, en el arte con- temporáneo isleño, tiene nombre y apellido: Pep Coll. La combinación de innumerables colores parece innata, a pesar de las teorías de los manuales, cuando Coll abraza todos los colores que le pueda ofrecer una paleta llena de vivencias y recuerdos, siempre que comporte huir de nuestro día a día. Su atrevimiento es incuestionable. Los colores más llamativos y a menudo inquie- tantes conviven con colores suaves y relajantes, pasando del pincel a la tela o al papel con acierto y armonía. Elementos como la media luna, formas que nos transportan a los patios de nues- tra infancia o a la pared de algún convento, casas que atienden a formas pri- mitivas, gusanos retorcidos, zigzags que desdibujan eróticamente el triángulo, cuadrados sometidos por líneas cruzadas, círculos, flechas que siempre te guían Abreme una ventana… Biel Font. Fotos: Brigitte Lucke

- 23. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 23 circles, and arrows that always point upwards create a balance, always governed by colour, seeking relief so as to leave no room for oppressive anguish. For some time, this world has found its limbo in a round format evocative of a portho- le, because the Pep Coll, who is most prone to fantasizing has perhaps exchanged having both feet on the ground for a long sea voyage in order to maintain his freedom of expression, because the world that emerges from his imagination is free. hacia arriba…entonan el equilibrio, siempre regidos por el color, buscando dis- persarse sin dejar sitio para la angustia opresora. Desde hace un tiempo este universo ha encontrado su limbo en el formato circu- lar, evocando el ojo de buey…porqué quizás el Pep Coll más fantasioso ha cam- biado los pies en tierra firme por un periplo por mar para conservar su libertad expresiva; porque libre es el universo que surge de su creatividad.

- 24. 24 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 Everything has a reason, everything is everything that happens, whatever happens, everything that happens has a reason. (Gilles Deleuze) Mercedes Laguens rescues these words from Deleuze, which are themselves a fold or loop, for the exhibit inaugurating on the 30th at the Aba Art Gallery in Palma. Since Skin of Paint, the exhibit she did at Casal Solleric in 2004, one could not have been able to see one of her individual exhibits in Palma. Those that follow her work were able to see her exhibit, Lies grow like Pinocchio’s nose, at Son Tugores, Alaró in 2006. This time, she presents us with a group of pieces whose conducting thread is the concept of the fold, a paradoxical proposal since the entire exhibit is the spread of a single work. The paintings on large and small canvas, the drawings on paper, and the ceramic objects, of which we were able to see an example at Palma City and at Son Tugores, will allow us to intuit and deduct the trails left by the author, about the reflexion in regards to the fold and to the passing of time. The painter, who also writes, leaves us clues to decipher what’s presented. The fold is the painting and also the experience. The painting itself doesn’t exist because, as it is artificial, it’s pure experience and folds with it. Todo tiene una razón, todo es todo lo que suceda, suceda lo que suceda, todo lo que sucede tiene una razón. (Gilles Deleuze) Mercedes Laguens rescata estas palabras de Deleuze, que son en sí mismas un pliegue o un bucle, para la exposición que el día 30 inaugurará en la galería Aba Art de Palma. Desde Piel de Pintura, la exposición que hizo en el Casal Solleric en el 2004, no se había podido ver en Palma una muestra individual suya, los que la si- guen pudieron ver en Son Tugores, Alaró, en el 2006 su exposición Crecen mentiras como nariz de Pinocho. Esta vez nos presenta un conjunto de obras cuyo hilo conductor es el concepto de pliegue, propuesta paradójica ya que toda exposición es el despliegue de un traba- jo. Las pinturas sobre tela de gran y pequeño formato, los dibujos sobre papel y los ob- jetos cerámicos, de los cuales ya pudimos ver algún ejemplo en un Ciutat de Palma y en Son Tugores, nos permitirán intuir, deducir los rastros que la reflexión en torno al pliegue y al paso del tiempo deja la autora. La pintora, que también escribe, nos deja pistas para descifrar lo presentado. El pliegue es la pintura y también la vivencia. La pintura por sí sola no existe porque, siendo artificio, es pura experiencia y se pliega con ella. PLIEGUE: TIEMPO VESTIDO ?????????????????????????

- 25. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 25 Mercedes Laguens talks to us about painting, her history, the folds and drapes, the white ruffs over black background in baroque portraits, the “origami-headscarf” on the head of Young Woman with a Water Pitcher by Vermeer, an artist that is ever present for M. Laguens for his luminous space, for the colour. She also reminds us that the painting is time and space that evokes continued creation and, of course, also evokes the fold. And it folds her name in its initial, the M, and by doing so it paints itself in the folded plain. And spreading it challenges us: what we see isn’t an image; it’s a look; since it’s the look that gives it the tone, the criteria with which it is looked at. And like all folds, what begins returns to the end. Therefore, another quote, this time by the painter herself: Wrapping, packaging, opening, spreading, unfolding; time is an elastic mass of cooked folds of shortcrust pastry. Mercedes Laguens nos habla de la pintura, de su historia, de los pliegues y drapea- dos, de la gorguera blanca sobre fondo negro de los retratos barrocos, del “pañuelo- origami” en la cabeza de La mujer joven con jarro de agua de Vermeer, artista que siempre tiene presente M. Laguens por su espacio luminoso, por el color. También nos recuerda que la pintura es tiempo y espacio que evoca el hacer continuado y, cómo no, también evoca el pliegue. Y pliega su nombre en su inicial, la eme, y al hacerlo se pinta en plano plegado. Y desplegando nos lanza un reto: lo que vemos no es imagen, es mirada; ya que es la mirada lo que da el tono, el criterio con el que se mira. Y como todo pliegue, lo que empieza vuelve en el final. Por tanto otra cita, esta vez de la propia pintora: Envolver, empaquetar, abrir, desplegar, desdoblar; el tiempo es una masa elástica de pliegues cocidos de pasta brisa.

- 26. Mònica Fuster “Among Them”, 2007 Dibujo mural (tríptico), 2 x 4 m Lápiz, carbón y bolígrafo sobre papel

- 28. 28 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 Cause : Consequence Body : Shadow Memory : Desire Desire : End-of-desire Conception : Execution Rehearsal : Performance Myth: Insight Archetype : Prototype Past : Present Dream : Remembrance Call : Answer Echo : Echo Answer : Question Future : Present Desire : Pain Pain: Hope Hope : Action Action : Regret Non-action : Regret Life : Regret Life : Death Life : Art (A) Cause : Consequence “One fine morning, I awoke to discover that, during the night, I had learned to understand the language of birds. I have listened to them ever since. They say: ‘Look at me!’ or: ‘Get out of here!’ or: ‘Let’s fuck!’ or: ‘Help!’ or: ‘Hurrah!’ or: ‘I found a worm!’ and that’s all they say. And that, when you boil it down, is about all we say. (B) (Which of those things am I saying now?)”

- 29. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 29 (A)-Fragmentos del texto “From cause to consequence (and back again)”, 2008 por George Stolz, texto escrito para el Catàlogo Fábula fabulae, de Mònica Fuster. (B)-Cita: Hollis Frampton, “Pentagrama para conjurar la narrativa” Causa : Consecuencia Cuerpo : Sombra Memoria : Deseo Deseo : Fin de deseo Concepción : Ejecución Ensayo : Actuación Mito : Perspicacia Arquetipo : Prototipo Pasado : Presente Sueño : Recordación Llamada : Respuesta Eco : Eco Respuesta : Pregunta Futuro : Presente Deseo : Dolor Dolor : Esperanza Esperanza : Acción Acción : Arrepentimiento No-acción : Arrepentimiento Vida : Arrepentimiento Vida : Muerte Vida : Arte (A) Causa : Consecuencia “Una hermosa mañana desperté para descubrir que, durante la noche, había aprendido a entender el lenguaje de los pájaros. Desde entonces siempre les he escuchado. Dicen: “¡Mírame!”, o “¡Fuera de aquí”, o: “¡ A follar!”, o “¡Socorro!”, o “¡Hurra!” o “¡He encontrado un gusano!”, y eso es todo lo que dicen. Nosotros si lo pensamos no decimos mucho más. (B) (¿Cuál de esas cosas estaré diciendo yo ahora?)”

- 30. 30 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 Fotografo invitado: Rafal Morey Millers Ten

- 31. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 31

- 32. 32 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 According to scientific studies, if the network of neurons that makes up our brain were to be stretched out, the extended distance they would occupy would be equiva- lent to fourteen kilometres, of which apparently we use but a little over a centimetre. In that miniscule portion we develop our cognitive capacities, our perception and comprehension of that which exists. From that reduced potential, we experience our physical and mental condition. It’s a limitation that the newest technological discover- ies are expanding to limits that were unthinkable until now. The synergy between scientific discovery and artistic interests explains that long, spec- ulative tradition which goes from the optical investigations of Dutch paintings and im- pressionism, to experimental photography, to kinetic painting or environmental art. And despite the fact that all artists have wanted to capture that which belongs to their own time, some have been especially fortunate in their desire to follow that magical thread that science places over that thing we call reality. New discoveries, new technological advances, and all that we know or thought we knew could end up altered. Según algunos estudios científicos la extensión que ocuparían las redes neurona- les de nuestro cerebro si fueran desplegadas sería el equivalente a unos catorce kilómetros, de los que al parecer sólo utilizamos algo más de un centímetro. En esa porción minúscula se desarrollan nuestras capacidades cognitivas, la percepción y comprensión de lo existente. Desde esa potencialidad reducida, experimentamos nuestra condición física y mental. Una limitación que los nuevos descubrimientos tecnológicos se ocupan de ampliar hasta límites por ahora impensables. La armonización de las búsquedas científicas con el interés artístico explica esa larga tradición especulativa en la caben desde las investigaciones ópticas de la pintura holandesa y el impresionismo, hasta la fotografía experimental, la pintura cinética o el arte ambiental. Y a pesar de que todos los artistas han querido plasmar lo que es propio de su tiempo, algunos han resultado especialmente afortunados en su deseo de seguir ese hilo mágico que la ciencia tiende sobre eso que llamamos realidad. Nuevos descubrimientos, nuevos avances técnicos y todo aquello que sabemos o creíamos saber puede quedar trastocado. ANN VERONICA JANSSENS “CUANDO EL PENSAMIENTO Y LA EXPERIENCIA SE HACEN POESÍA” Espai d’Art Contemporani de Castelló y Galería Toni Tàpies de Barcelona Pilar Ribal

- 33. M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A 33 This meant, for example, that until Marey froze their image in the air, painters er- roneously represented the horses’ gallop, and it wasn’t until the introduction of the railroad that a painter named Turner was able to paint those vaporous atmospheres resulting from the combination of rain, wind and speed. Photography, the filmmaker, the digital image… the arch that encompasses the sensory, visual and intellectual continues to be treated to an infinity presently impossible to calculate. To take human perception to a limit and manipulate our physical and mental ex- periences to the point of confusing and altering them is the challenge undertaken by the work of Ann Veronica Janssens, an artist with an extensive and recognized trajectory that has, for more than thirty years, turned the time-space-form-light equation into a consistent process of plastic investigation. Breaking the Kantian premise that only that which exists in time and space can be perceived, Janssens realized lumi- nous installations that break convention and certainty, blurring the boundaries of that which is tangible and intangible and making us perceive phenomena as invis- ible as the movement of a planet or the explosion of light radiating off a light bulb. Her sculptural proposals are as consistent as they are ethereal, able to constitute the luminous materialization of colour or cap- turing the volume of air with a transparent gel. Time’s elasticity, one of the philosophi- cal topics best depicted in her work, is one of the aspects questioned in some of her best-known installations, like the pavilion she realized for her exhibit at the Berlin National Gallery. A replica of that installation currently occupies the public space in front of Castellon’s Espai d’Art Contemporani in order to expose the visitor to the perturbing experience of finding oneself lost in the middle of a thick, coloured mist. This exhibit, titled by Janssens, Are you experienced?, and commissioned by Joël Benzakin and Michèle Lachowsky, is the first she’s institutionally produced in Spain and is without a doubt one of the most interesting proposals in the national circuit. Four specific projects: the editing of an artist’s book with all the visual ar- chives of the artist, a sound installation (a terrifying roar of unknown origin), sev- eral luminous projections where we find ourselves in the dominion of immaterial painting, and the previously mentioned pavilion, integrate this ambitious initiative which lets us discover the most subtle registers of a work with such conceptual and plastic potency. Coinciding with this institutional presentation, Janssens individual exhibit is at the Toni Tàpies Gallery in Barcelona, at which we find such beautiful pieces as Cocktail Sculpture or Tropical Moonlight. These sculptural works, metaphorically and literally exploring the reflection of light and the optical illusion of a moving space, are com- plemented by a series of recent audiovisual installations: registers of the workings of lunar and solar observatories and light metering exercises. Thought through scientifically, designed to the millimetre, plastically impeccable… it’s easy to be taken by the suggestive capacity of Ann Veronica Janssens’ pieces. Her formal universe is like a complex network of constellations whose philosophical breath and sensorial qualities take us to that neighbouring sphere where thought and experience become poetry. Así, por ejemplo, hasta que Marey no congeló su imagen en el aire, los pintores representaban erróneamente el trote de los caballos, y no fue hasta la introducción del ferrocarril que un pintor llamado Turner supo pintar esas atmósferas vaporosas resultado de la combinación de la lluvia, el viento y la velocidad. La fotografía, el cinematógrafo, la imagen digital... el arco de lo visual, intelectual y sensorial sigue tensándose hasta un infinito por ahora imposible de calcular. Llevar la percepción humana a un límite y manipular nuestras experiencias físicas y mentales hasta confundirlas y alterarlas es el reto que asume el trabajo de Ann Veronica Janssens, una artista de extensa y reconocida trayectoria que lleva más de treinta años haciendo de la ecuación tiempo-espacio-forma-luz un consistente proceso de investigación plástica. Rompiendo la premisa kantiana acerca de que sólo aquello que existe en el tiempo y el espacio puede ser percibido, Janssens lleva a cabo instalaciones lumínicas que rompen con las convenciones y las cer- tidumbres, desdibujando las barreras de lo tangible y lo intangible y haciéndonos percibir fenómenos tan invisibles como el movimiento de un planeta o el estallido de luz de una bombilla. Sus propuestas escul- tóricas son tan consistentes como etéreas, puediendo consistir en la materialización luminosa del color o la captación del volu- men del aire con gel transparente. La elas- ticidad del tiempo, una de las cuestiones filosóficas de más calado en su trabajo, es uno de los aspectos puestos en cuestión en algunas de sus instalaciones más co- nocidas, como ese pabellón que realizara para su exposición en la Galería Nacional de Berlín cuya réplica ocupa actualmente el espacio público frente al Espai d’Art Contemporani de Castelló para exponer al visitante a la perturbadora experiencia de hallarse perdido en medio de una espesa bruma coloreada. Esta exposición comisariada por Joël Benzakin y Michèle Lachowsky que Janssens ha titulado Are you experienced?, es la primera que realiza institucionalmente en España, sin duda una de las propuestas más interesantes del circuito nacional. Cuatro proyec- tos específicos: la edición de un libro de artista con todos los archivos visuales de la artista, una instalación sonora (un estruendo pavoroso de origen desconocido), varias proyecciones lumínicas en las que nos hallamos en el dominio de la pintura inmaterial, y el ya mencionado pabellón, integran esta ambiciosa iniciativa que nos descubre los más sutiles registros de un trabajo tan conceptual y plásticamente potente. Coincide con esta presentación institucional la exposición individual de Janssens en la Galería Toni Tàpies de Barcelona, en la que encontramos piezas tan hermosas como Cocktail Sculpture o Tropical Moonlight. Estos trabajos escultóricos que explo- ran metafórica y literalmente la reflexión de la luz y la ilusión óptica de un espacio en movimiento, se complementan con una serie de instalaciones de audiovisuales recientes: registros del funcionamiento de observatorios lunares y solares y ejercicios de medición de la luz. Científicamente pensadas, milimétricamente diseñadas, plásticamente impecables... es fácil dejarse llevar por la capacidad de sugestión de las obras de Ann Veronica Janssens. Su universo formal es como una compleja red de constelaciones cuyo aliento filosófico y cualidades sensoriales nos llevan a ese ámbito limítrofe donde el pensamiento y la experiencia se hacen poesía.

- 34. 34 C U L T U R A M A L L O R C A M A R Ç 2 0 0 9 8 To read a manga it’s important to start at the end. This is due to the fact that the Japa- nese read from right to left, something that aficionados are used to, but that since the first years of the Nipponese comic books’ incursion in the US and Europe has caused some editors to invert the pages in order to adapt them to the western reader. This type of “standardization” exemplifies the ethnocentric vision that is typical of our culture, a translation that, in the case of Murakami, leads to a false understanding of his work, assimilated as a Japanese version of Pop Art or a simple and shameless commercial operation. In order to understand Murakami, it’s important to read it from the oriental and not the western: put simply, inverting the order of the pages. 7 The Warhol reference seems obligatory when confronted with Murakami’s work, but said comparison, if clearly plausible, tends to limit the comprehension of the Japa- nese’s piece. The search for a contemporary Japanese identity in a world globalized by the West is one of Murakami’s principal preoccupations, transcending in this way the Pop Art artisan’s discourse. Use of the comic book, advertising and consumer products by American artists didn’t have the critical intention nor the depth of ap- proach that is behind the recovery of the otaku culture, the use of manga and anime 8 Para leer un manga es preciso empezar por el final. Esto se debe a los japoneses leen de derecha a izquierda, un hecho al que los aficionados se han acostumbrado ya, pero que desde los primeros años de incursión del comic nipón en EE.UU. y Europa ha llevado a algunos editores a invertir las páginas para acomodarlas al lector occidental. Este tipo de “normalización” ejemplifica la visión etnocentrista propia de nuestra cultura, una traducción que, en el caso de Murakami, conduce a una falsa comprensión de su obra, asimilada como una versión japonesa del Pop Art o una simple y descarada operación comercial. Para entender a Murakami es preciso leerlo desde oriente y no desde occidente: en cierto modo, invertir el orden de la lectura. 7 La referencia a Warhol parece obligada cuando se afronta la obra de Murakami, pero dicha comparación, si bien plausible, tiende a limitar la comprensión de la obra del japonés. La búsqueda de una identidad japonesa contemporánea en un mundo globa- lizado desde occidente es una de las preocupaciones principales de Murakami, quien trasciende de esta manera el discurso de los artífices del Pop Art. El uso del cómic, la publicidad y los productos de consumo que hicieron los artistas americanos no tenía la intención crítica ni la profundidad del planteamiento que se halla tras la recuperación Murakami Takashi (léase de atrás hacia adelante) Pau Waelder Fotos: Guggeheim Bilbao