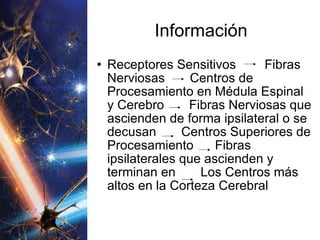

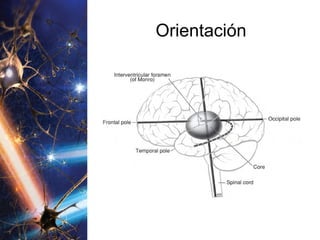

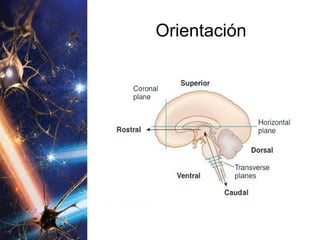

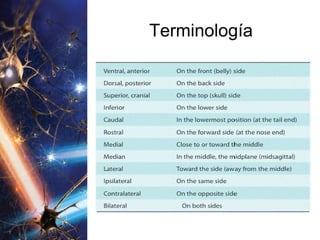

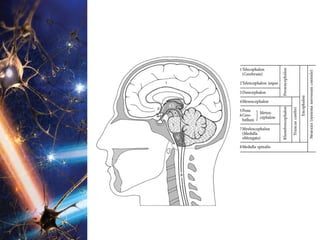

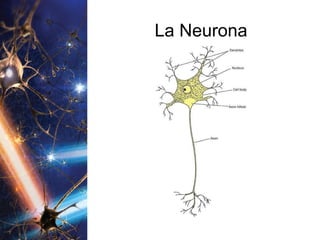

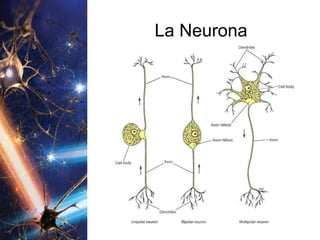

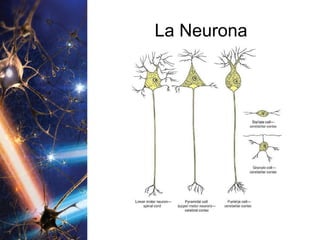

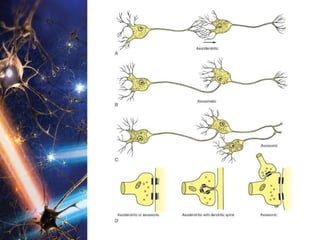

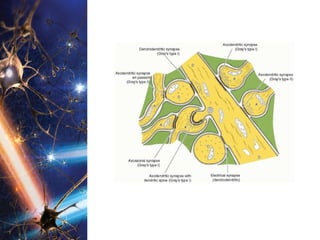

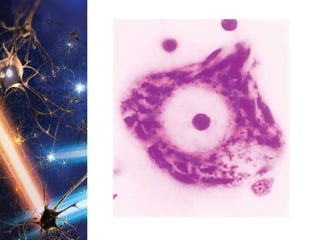

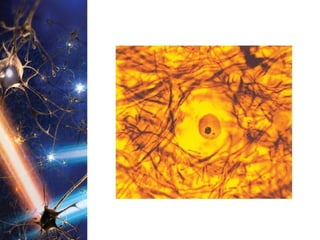

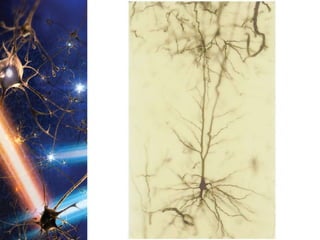

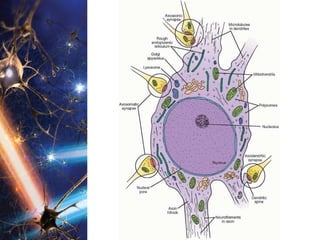

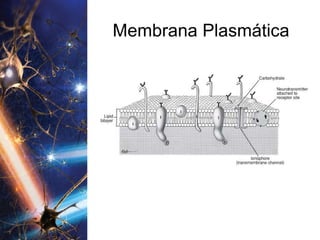

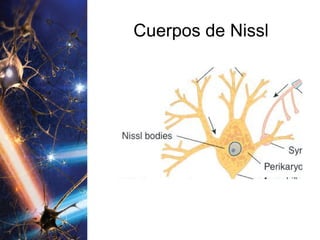

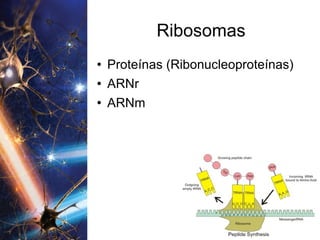

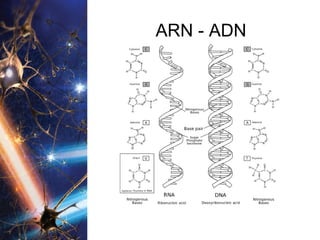

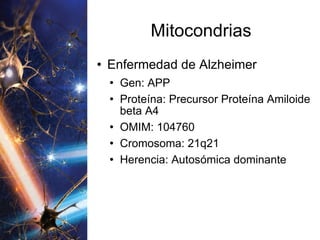

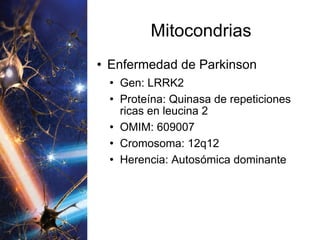

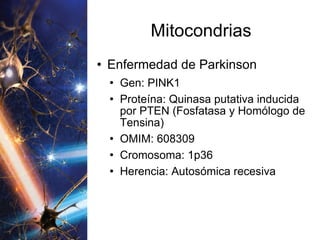

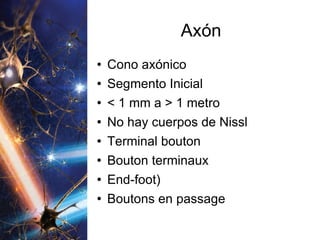

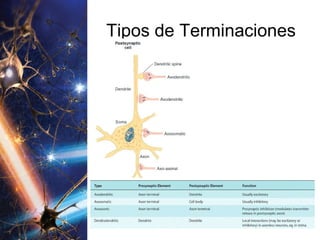

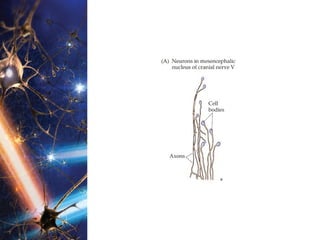

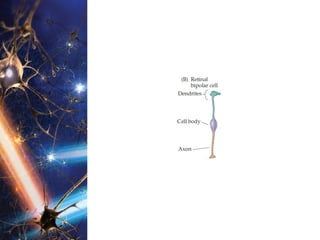

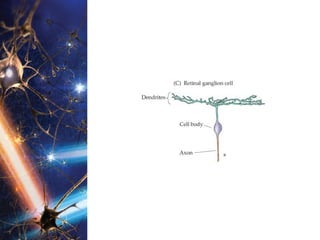

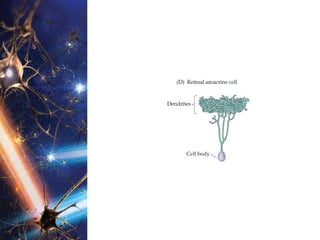

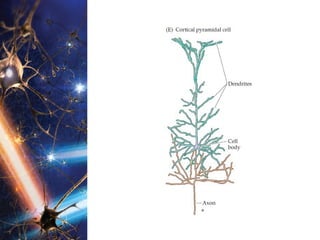

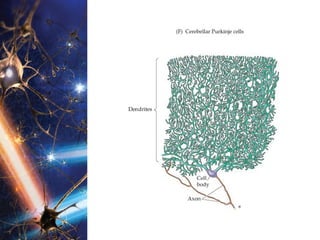

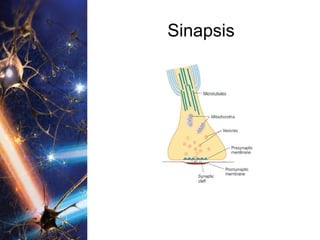

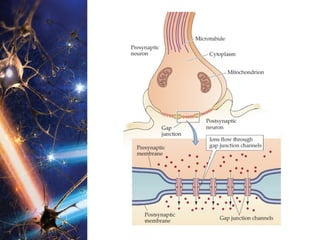

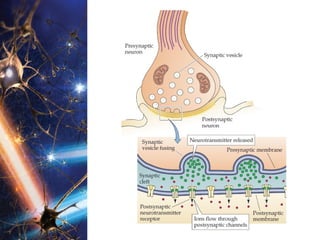

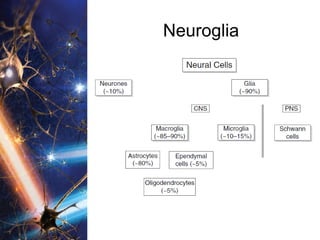

El documento proporciona una introducción al sistema nervioso humano, describiendo las divisiones anatómicas y funcionales del cerebro y la médula espinal, las señales del sistema nervioso periférico y central, y la estructura y función básica de las neuronas, membranas celulares, núcleos, mitocondrias y otros orgánulos. También discute varias enfermedades neurodegenerativas como la enfermedad de Alzheimer, Huntington y Parkinson.