Este documento presenta un número de la revista trimestral Artecontexto. El número 16 incluye un dossier sobre la enseñanza de las artes visuales con artículos de Luis Camnitzer, Armando Montesinos, Justo Pastor Mellado, Sara Diamond y Daniel Canogar. También incluye un artículo de Ibon Aranberri sobre la identidad comunitaria en Portugal, información sobre la situación actual en Portugal, una sección sobre cibercontexto y críticas de exposiciones. El número fue publicado en 2007 y cuenta con la colaboración de varios aut

![DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 43

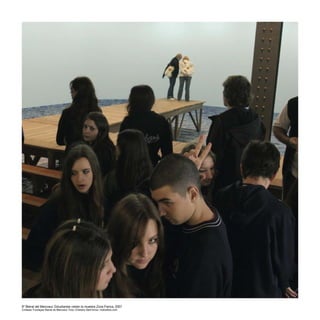

changed and they ways that the current and future equally needs

dialogues across disciplines. Evidence suggested that the once hard

lines between art and design, art and architecture, are disrupted. This

was true in some parts of the professional world, amongst younger

faculty members and within the student population as well as in

the context of exhibition and critical discourse. Art students were

interested in some of the problem-solving approaches of design and

design students were eager to work in more experimental ways or

borrow the aesthetics of art-making. For example, the Design faculty

offers a popular course entitled Think Tank where students and faculty

address issues in the world, from creating energy efficient low cost

lighting for a neighborhood, to developing a campaign and approach

towards replacing Styrofoam with recyclable containers. This course

is attractive to students in the Art faculty as well.

Our new Interdisciplinary Studio Graduate Program expresses

this integration of knowledge. It is cross-disciplinary and allows

students to work with sciences, engineering, social science, as well as

concentrate in art or design or combine art and design. Our Curatorial

and Critical Practice Masters stresses exhibition design, producing

and entrepreneurial skills as well as literacy and curatorial knowledge.

We are developing a new media degree with an engineering university

that will allow students to pursue a Masters of Fine Art in Design, Art,

and an MA in Management or a Masters of Science.

The strategic plan lays out a number of values to which the entire

institution is accountable that emerged through the foresight work

of building scenarios, our research and attendant dialogues, “OCAD

values accessibility, cultural diversity, equitable global citizenship, art

and design advocacy, aesthetic and formal excellence, sustainability

and entrepreneurship.” These ideas in the mission correspond closely

to a set of themes that cut across the disciplinary divides and provide

a means to rethink curriculum categories, both what we are teaching

and the ways that this knowledge is organized, allowing large-scale

institutional initiatives and partnerships. The themes represent long-

term trends in culture and society. These are:

ò Sustainability in art and design approaches

and institutional practices and culture;

ò Cultural diversity;

ò Contributing to technological innovation,

including the digital future;

ò Wellness and health;

ò Cross-disciplinary experience; and

ò Leading in and developing contemporary ethics.

The strategic plan takes up a position for an art and design

institution that is historically less frequent in Canada and the USA than

in the United Kingdom, India and some European contexts. We are

working to position our institution as a centre for research, both in

the disciplinary areas of art, design and related social sciences and

humanities, but also in partnership with other institutions, sectors and

forms of knowledge. This has meant that OCAD is now working with

health science researchers to analyze patient facility use patterns and

the flow of services, with engineers developing sensor technologies

to promote biodiversity, with mobile telephone engineers and service

providers on a gaming engine and content for the mobile phone, with

business analysts to understand the transformation of advertising

patterns –there are significant examples that have emerged in just two

years, since we chose to open our institutional doors to research.

The strategic plan argues that 21st

century universities must be

strongly connected to the larger community, both the local community

that surrounds it and the wider global community. In Toronto, Canada’s

most significant English Canadian cultural centre and one of the

most ethnically diverse communities in the world, this offers fantastic

opportunities as well as challenges. We are making certain that student

and faculty recruitment, support services, and curriculum takes into

account such diversity. We are also building programs to reach out to

the large Aboriginal population in the area and beyond. This requires

significant resources and a cultural shift within the institution.

This repositioning means that OCAD acts not only as a university

but as a cultural centre and intellectual hub. We are partnering with local

and international centers and institutions, hosting events, conferences,

and at the core of local cultural activities. An example is Toronto’s

massive Nuit Blanche, an event that mobilizes hundreds of thousands

of participants, where our institution acts as one of the hubs –something

that was not part of the institution’s culture in the near past.4

More than this, we are trying to become an institution that keeps its

eyes on the future while doing its best to engage the current generation

of students in strengthening and bettering the OCAD of today. This

means that we are increasingly relying on face-to-face forums to

discuss ideas and issues that effect students, but on participatory

technologies. Striking the balance between looking ahead, a

demanding and rigorous learning environment and the engagement

of students and faculty who are focused on the present will define the

success or failure of many of these ideas –for our university but also

for others who are updating their approach. What is clear is that we

need to be inclusive, to provide a much wider context of knowledge

than was traditionally the case in art and design universities, colleges

or institutes and to find a balance between making and its analysis.

Ÿ Sara Diamond is the President of the Ontario College of Art & Design,

a specialised undergraduate and graduate degree granting university in

Toronto, Candada. Diamond is a software researcher and designer and a

media and performance artist. She contributes to scholarly writing about

the history of media art and art and technology.

NOTES

1.- Chicago, J. (2007) www.judychicago.com [Internet] (Accessed September, 2007).

2.- Weiner, L. (2006) www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_bio_162A.html [Internet]

(Accessed September, 2007)

3.- See www.ocad.ca (2007) [Internet] (Accessed 2007) for the full plan.

4.- Scotiabank Nuit Blanche www.scotiabanknuitblanche.ca [Internet] (Last accessed

December 2007)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton16-220308151108/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n16-43-320.jpg)