Este documento presenta información sobre la situación del sector cultural y artístico en España durante la crisis económica. Señala que la cultura ha sido uno de los primeros sectores en sufrir recortes a pesar de ser productivo y generar empleo. El sector del arte en particular es débil ya que está formado por microempresas, autónomos y trabajadores precarios con poca estructura industrial. Se necesitan políticas culturales sostenibles a largo plazo en lugar de sólo invertir en infraestructuras faraónicas.

![8 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER

This question was posed by Nacho Criado in a work he produced

in 1994. And it is appropriate to express the uncertainty felt by

a large number of citizens at present, as they are under siege

on a number of fronts: unemployment, precarious working

conditions, cuts, dismantling of the (emerging, in our country)

welfare society. These are the consequences of an international

crisis which, as we all know, did not happen as if by magic,

nor was it the result of an accident in the operations of global

economy, or even the fruit of the greed of a handful of heartless

speculators. Rather, it is the result of neoliberal policies,

market deregulation, the abdication on the part of states and

governments of their responsibilities and their unwise decision

to ask those responsible for the collapse for ways to escape a

crisis they themselves caused.

If we focus on our country, the cuts on healthcare and

education first affected culture, a sector whose members,

including those who are devoted to art, are witnessing the

exponential increase in their usual precarious situation.

At the same time, we are hearing that culture is not only an

economic engine but also a “strategic sector”, as was recently

stated by a high-ranking official in our central government. The

participants in the European Culture Congress spoke along the

same lines, during the event, which took place in September,

in Wroclaw. The thinker Zygmunt Bauman declared, during the

congress, that “The future of Europe depends on culture”. And

another of the participants, Philip Kern, pointed out, “at this time

it is necessary to situate culture at the heart of the social and

economic discourse of new society (…) and not only because

at present the cultural industry provides millions of jobs and

accounts for an important percentage of GDP (…) When we

speak about innovation we think only about technology, when in

fact this sector drinks from the ideas and trends which emerge

in the field of culture”.

In our country we speak about a productive sector, which

forms part of the Cultural Industries, which at present accounts

for 5% of GDP and which employs 900,000 people, without

including the indirect jobs it generates. A sector made up of

highly-trained people (57% are graduates), a strong capacity for

adaptation, flexibility and entrepreneurship,

giving rise to a greater potential for

development than other sectors; however,

these positive elements are not enough to

face a crisis of this magnitude.

We must take into account the fact

that in 2008 the investment in culture by the

General State Administration was 0.10% of

the total, a percentage which, as we know,

has been significantly reduced in the last

three years. We can conclude, then, that

it is a productive sector which generates

important resources even as it receives tiny

investments.

However, when we speak about Cultural

Industries, we must differentiate between

sectors such as the book industry, which

includes important publishing groups, or

the film industry–which, for example, enjoys

a specific soft credit line at the Instituto

EL ROTO, cartoon published in El País. View of the exhibition Sin realidad no hay utopía [Without Reality there is No

Utopia] at the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo (CAAC) Seville, 2011. Courtesy of the autho. Photo: Guillermo Mendo.

What To Do in Furtive Times. (Art, Culture, Crisis)

ALICIA MURRÍA*](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton32-220304083126/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n32-8-320.jpg)

![DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 41

tieron en shoppings o nuevos complejos habitacionales (como las

galerías Pacifico o la zona de Puerto Madero) que se desarrollaron

en la misma zona en la que crecieron villas de emergencia. Buenos

Aires también se había transformado con un consumismo desme-

dido alimentado por la ficción de que un dólar valía lo mismo que un

peso y por el crecimiento del mercado inmobiliario. A fines de 2001

el Fondo Monetario Internacional suspendió la decisión de continuar

subvencionando una economía que sólo lograba aumentar la deuda

del país. Creció el desempleo (alcanzando, entre desempleados y

subocupados, el 18,3%); el crédito dejó, abruptamente, de financiar

el consumo. Los capitales comenzaron a fugar de las reservas del

estado, y el gobierno, en un intento desesperado de controlar la cri-

sis, congeló los depósitos bancarios y decretó el corralito, es decir

la restricción del retiro de fondos de las cuentas a plazo fijo y de las

cajas de ahorro. El 19 y 20 de diciembre la población invadió las

calles de la ciudad batiendo cacerolas, reclamando la devolución de

sus fondos y repudiando a la clase política en su conjunto. El pre-

sidente De la Rúa renunció y Adolfo Rodríguez Saa, presidente por

pocos días, declaró el default [no pago] de la deuda pública de la

Argentina. Se produjo así la mayor suspensión de pagos de toda la

historia. El país quedaba fuera del sistema global de la economía.

Esta red de acontecimientos se asentaba en el proceso de re-

forma neoliberal cumplido en los diez años de gobierno menemista.

Los cambios involucraron también la informalización del empleo, el

abandono de políticas sociales, el aumento de la desocupación y

un acelerado proceso de marginalización y empobrecimiento de la

población que generó una forma de movilización popular, previa al

estallido de la crisis, que se expresó en los cortes de ruta [carretera].

En ellos la multitud se definía como unida, comprometida y carente

de líderes. Los cortes irrumpieron con una visualidad muy precisa: la

quema de llantas cuyo humo negro inundaba el cielo era la imagen

que permitía identificar con claridad de qué tipo de acción de pro-

testa se trata. Estas imágenes, profusamente reproducidas por los

medios, fueron un elemento central en la dinámica del conflicto.

Todas estas formas de protesta implicaron la migración de la

casa y el barrio a la barricada, la plaza y las calles del país. Allí

se expresaron frustración, necesidades, demandas y se articularon

tácticas de horizontalidad. El congelamiento de los depósitos ban-

carios intrumentado ante la fuga de capitales provocó la protesta de

los sectores medios que batían cacerolas en las calles y golpeaban

las puertas de los bancos. Hundidas, incluso perforadas, sus puer-

tas de metal dejan ver hasta hoy las marcas de la reacción frente a

la usurpación de los depósitos de los ahorristas.

La ciudadanía se rearticuló por relaciones de vecindad. En un

abierto cuestionamiento de todo el sistema político, el “ciudadano”

se identificó como “vecino” que, organizado en asambleas, recla-

maba a los políticos «que se vayan todos», asumiendo la organiza-

ción de la vida cotidiana en todos sus aspectos. Las plazas de la

ciudad se transformaron, el espacio público se convirtió en un ámbi-

to de trueque donde se intercambiaban los productos de consumo

básicos. La ciudad esplendorosa de los años noventa había mutado

en un sistema de precarización de la economía y de las relaciones

sociales que, al no ser mediadas ni por el sistema político ni por

el mercado, dieron una nueva jerarquía a las relaciones personales

como base desde la cual reconstruir formas de solidaridad y otor-

garle un nuevo significado al término ciudadanía: esta ya no se ejer-

cía a partir de sus representantes sino en forma directa y cotidiana.

Uno de los efectos más fuertes del impacto de la crisis en la

organización de las artes visuales fue la emergencia de los colecti-

vos de artistas. La calle y el debate conjunto reemplazaron al taller y

al artista individual que, por un tiempo, casi desapareció inmerso en

alguno de los tantos grupos. Si bien las formas de trabajo conjunto,

amalgamadas por ideas o por prácticas, existían antes de la cri-

sis, el grado de generalización que alcanzaron permite referirse, en

cierto modo, a una “colectivización” de la práctica artística.

Colectivos como el Grupo de Arte Callejero o Etcétera, activos

antes de 2001, o los que surgieron al calor de la crisis como el Taller

Popular de Serigrafía, Argentina Arde o Arde Arte!, para mencionar

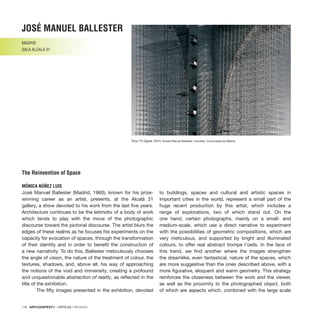

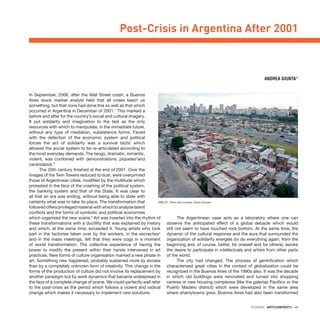

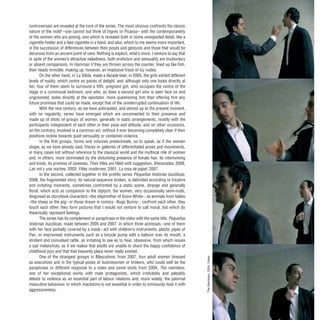

Ruta Nacional 22. Primera “pueblada” de Cutral Co por la anulación del contrato de la

planta de fertilizantes Agrium, Neuquén (Argentina). Fuente: Diario Río Negro, 24 de junio de

1996, p. 10. Foto: Pablo López, Río Negro. Cortesía: Diario Rio Negro](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton32-220304083126/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n32-41-320.jpg)

![42 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER

tan sólo algunos de los que surgieron en Buenos Aires, así como

el trabajo colaborativo de la revista Ramona o el proyecto Venus,

introdujeron una forma distinta de entender la creación artística, en

la que se desmarcaba el rol del creador y del espectador.6

Para el Grupo de Arte Callejero (GAC), desde fines de los años

noventa (1997) la calle es un ámbito de intervención.7

Lo hacen a

partir de los signos de señalización urbana, con el propósito de pro-

vocar ambigüedad y subvertir los sentidos establecidos. En sep-

tiembre de 2001 realizaron un escrache para denunciar a Miguel

Ángel Rovira, figura relevante de la Triple A (Alianza Anticomunista

Argentina), en ese momento jefe de seguridad de Metrovías, el sub-

terráneo de Buenos Aires. La intervención se extendió a todo el

sistema de subterráneos [líneas de metro]. Imprimieron 30.000

escrachepass (en alusión al número de desparecidos durante la

última dictadura militar) cuyo diseño imitaba al de los pases del

subte (subpass) y contenía información acerca del represor Rovi-

ra. Los distribuyeron en las bocas de expendio de pases del sub-

te, presentándose con un discurso parecido al de un vendedor

ambulante (poniendo de ese modo en escena elementos vincu-

lados al complot y a lo clandestino). Además imprimieron 6.000

stikers que adhirieron a las puertas y ventanas de los vagones. El

19 y 20 de marzo el GAC estaba en la calle, organizando la ac-

ción urbana Invasión, en la que lanzaron 10.000 paracaidistas en

miniatura desde un edificio del microcentro. En la semana previa

habían invadido el centro de la ciudad con símbolos estructura-

dos desde imágenes militares como el tanque (multinacionales),

misiles (propaganda mediática), soldados (fuerzas represivas que

requiere el poder neoliberal).

Las intervenciones del grupo Etcétera, por su parte, vincu-

lan la política y el humor. En el momento anterior al estallido de

la crisis trabajaron sobre las condiciones que la harían estallar.

El grupo también colabora con organizaciones de derechos hu-

manos como H.I.J.O.S. y actúa directamente sobre las situa-

ciones planteadas por la crisis. Por ejemplo, a propósito de la

retención de los depósitos bancarios hicieron El mierdazo, una

acción que convocaba a la sociedad a llevar sus propios excre-

mentos a los bancos, como forma de expresar su opinión hacia

la clase financiera. El aspecto escatológico de esta intervención

no es ajeno al espíritu surrealista que impregna sus acciones.

Esta estuvo acompañada de una performance en la que uno de

los integrantes del grupo, disfrazado de oveja, defecaba frente

al público.

Otro ejemplo proviene de un grupo que se forma al calor

de la crisis: el Taller Popular de Serigrafía, creado en febrero de

2002.8

El Taller surge vinculado a la asamblea popular de San Tel-

mo, en la plaza Dorrego. La primera reunión fue una clase abierta

para enseñar la técnica de impresión serigráfica. En 2003 se in-

tegraron a la lucha de las trabajadoras de Brukman por recuperar

esta fábrica, que volvieron a poner en funcionamiento cuando

sus dueños la abandonaron dejando a todos sin trabajo, y de la

que fueron despedidas y expulsadas una vez que habían logrado

poner la fábrica de nuevo en marcha. El estampado de afiches, re-

meras [camisetas] o banderas (los soportes que la gente aportaba

para la impresión) se realizaba en el contexto de la manifestación

o de la ocupación, buscando proveer una imagen que sirviera de

identificación.

Contagio y organización son términos clave en la definición de

la dinámica de los colectivos. Desde estos contactos cercanos, con el

grupo, con los que se aproximan a él, con las comunidades afectadas

por un conflicto específico, algunos plantean la necesidad de vincu-

larse con otros grupos que tengan los mismos propósitos, constituir

redes, partir de la calle, el barrio, la ciudad, para alcanzar el mundo.

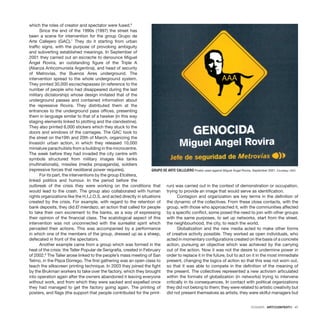

Bancos con vallas para protegerse de la reacción de los ahorristas, agosto de 2001.

Foto y cortesía: Andrea Giunta.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton32-220304083126/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n32-42-320.jpg)

![ARTECONTEXTO · 77

MÚSICA

Keith Rowe

Álbum: Concentration Of The Stare

Sello: Bottrop-Boy

JOSÉ MANUEL COSTA

La historia de la modernidad artística podría escribirse como la

peculiar relación entre música y pintura. Dicha relación ha tenido

que ver con el proceso hacia la abstracción, donde la pintura

trataba de seguir a la música como la más “abstracta” de las

artes, un ideal al que se debía tender. Esto se hizo explícito en

textos de Kandinsky o Klee, y en los títulos de muchas pinturas

o esculturas de la modernidad, como composición, sonata, sin-

fonía, etc.

Andando el tiempo, la pintura se había liberado casi total-

mente de la representación y entonces fue la música, atrapada

en el sentimentalismo y la descripción del romanticismo la que

buscaba ejemplos externos que emular. Y en esto llegó una

parte de la escuela de Nueva York trayendo las pinturas inexpre-

sivas de un Barnett Newman y, sobre todo, de un Mark Rothko.

Por otro lado, la música contemporánea americana se estaba

sacudiendo los dictados del dodecafonismo y el serialismo y

acabó dando, entre otros, con Morton Feldman.

Ambos coincidieron en un lugar de culto sin adscripción, la

Rothko Chapel de Houston (donada por el matrimonio de Menill),

construida para catorce oscuras pinturas de un Rothko al borde

del suicidio e inaugurada en 1971 con música de Feldman, lla-

mada también Rothko Chapel. Puede argumentarse, que este es

el filo de la navaja donde pintura y música se reúnen en condi-

ciones de igualdad. Rothko sabía quién era Feldman, pero segu-

ramente no pensaría en él. Feldman sabía muy bien quien era

Rothko y que su obra daría nombre a la capilla, pero su música

no trataba de emular su obra, sino de responder ante ella.

Desde entonces son muchos los músicos que se han ocu-

pado del pintor, entre ellos On, Joan LaBarbara, Ken Vandermark,

Bernhard Günter, Brian Eno, Fourm… Incluso ha habido un muy

apreciable grupo de electrónica llamado Rothko. Y es curioso,

prácticamente, todas las piezas son de un nivel superior y en

ningún caso tratan de ilustrar musicalmente una pintura.

Eso es también lo que ha hecho hace bien poco el trans-

guitarrista inglés Keith Rowe (1940, fundador de AMM) en

un álbum que es una sola pieza de 41 minutos. Rowe realizó

Concentration Of The Stare [Concentración de la mirada] como

una larga improvisación en la misma Rothko Chapel. Usó la gui-

tarra eléctrica, dispuesta de forma horizontal sobre una mesa,

no tanto como el instrumento que conocemos, sino como una

fuente de sonido que puede ser excitada casi de cualquier ma-

nera y con casi cualquier medio, desde resortes a plumas, lápi-

ces o cualquiera de los múltiples objetos que Rowe saca de su

equipaje de manera no demasiado ceremonial.

La técnica tradicional de la improvisación, a falta de una

partitura o, cómo en el caso de Rowe, de cualquier instrucción o

acuerdo previo, se basa generalmente en lo que se llama expan-

sión-compresión, que puede tener que ver, o no, con mayor o

menor volumen, mayor o menor velocidad (medida no como un

simple tempo, sino como acumulación de notas-sonidos en un

lapso temporal), mayor o menor insistencia en un tema…

En este disco, realizado completamente en solitario, Rowe

sigue a grandes rasgos esa técnica. Por lo general su sonido

es más expansivo, mientras aquí, entre estas pinturas, se deja

llevar por el espíritu del lugar, la meditación sin adscripción re-

ligiosa, y también se simplifica, portando en la música la con-

centración de la mirada que hace vibrar los cuadros de Rothko y

los convierten en una superficie palpitante por la que un espíritu

dispuesto puede entrar en una dimensión diferente. Música o

pintura, tanto da, si vibran de la misma forma.

Keith Rowe en Kytn 08. Foto: Autor desconido. Cortesía: Arika](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton32-220304083126/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n32-77-320.jpg)

![78 · ARTECONTEXTO

No apagar la luz [Don’t Turn Out the Light] is the title of a book, or a

journal, or an artist’s book; it is also the title of an exhibition which,

in an expanded way, widens the very concept of “exhibition” at a

certain art centre. The fact that this review appears in the “Books”

section should help us read it with one eye on the parameters of an

exhibition review (or almost, or excessively, depending on its role),

while we also pay attention to that same quantification of what is

observed, in the sense of a dramatic (artistic) action is condensed in

an object which, for philological convenience, we agree to describe

as “book” (or almost, o excessively, depending on its role as well).

To simplify things: No apagar la luz should be seen and read under

both these premises, as both offer the key which gives us access

to one of the most consistent, unusual, lucid, and intelligently

emotional art productions made in Spain in the last two decades.

Its author is Gustavo Marrone (Buenos Aires, 1962).

In the book as such we find a Brancusian “infinite column”

(the fact that the book ends on the last page is a necessary

commercial convention, which does not match the endless

expressive sequence devised by the artist) from which Gustavo

Marrone has drawn the best and most essential elements in his

aesthetic ideas, but at the exhibition organised at La Panera in

Lleida we can observe the domestic scenographic (the studio, or

the back room of all art productions, or the kitchen of powerful

alchemy …) from which the artist invites us to a non-artistic but

aesthetic consideration of what is created. We are referring to

a consideration with a strong sense of social criticism, where

pious humanism and the most expressionistic sensuousness and

eroticism come together to create one of the most secret, and, in

a noble paradox, most luminous works in the Spanish art scene.

Few artists have achieved such a perfect fit between opposing

elements: light and darkness, abstraction and figuration, tragedy

and humour, social criticism and frivolous hedonism, baroque

writing and Buddhist void, beauty and ugliness.

No apagar la luz is a doomed archive, aware, as in Lezama

Lima’s poem, that “what is hidden completes us”. A counter-

archive which has been built over the years, a work in progress

with a blurred beginning in time, and an uncertain, and impossible,

ending. A wilfully illegitimate documentation, in its lucidity

and horror, where drawings, sketches, aphorisms, gestures,

sentences, ideas, reactions and melancholy come together to

create an expressive universe of strange and fatal beauty. A

paradigm which can easily be used as a slogan for almost all of

Marrone’s work, to the extent that its commitment to life brings

us closer to a judicious understanding of events, in the sense

of everything linked to what is human. It is a very welcome title,

here and now. No apagar la luz invites us to conduct a different

reading of a book, and a diverse visualisation with regards to

the art exhibition in itself. Like a hemistich between two stanzas,

what is left is a white and luminous space of questioning,

a ferocious shriek like that which, given the legend behind it,

should not matter, when Goethe screamed, at his final moment

on this earth: Light! More light!

GUSTAVO MARRONE

Don’t Turn Out the Light

LUIS FRANCISCO PÉREZ

BOOKS

No

apagar

la

luz,

2011.

Courtesy:

La

Panera](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton32-220304083126/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n32-78-320.jpg)

![CRÍTICAS / REVIEWS · ARTECONTEXTO · 85

de la ciudad, al que ilumina beatíficamente y opone un lema

que bien podría ser el de la exposición: Emancipate yourself.

Hay, sin duda, piezas extraordinarias, así Empire’s

Borders, el video de Chen Chieh-Jen, o la película Elmina,

del norteamericano Doug Fishbone, que suma a las

pecualiaridades de su rodaje –un hombre blanco, artista, en

Ghana– las de su distribución y comercialización accesible.

No es de extrañar que la presencia de artistas latino-

americanos sea, junto a la de los irlandeses, predominante

en la selección. Comparecen así el siempre eficaz y convin-

cente Fernando Bryce –cuyas series de dibujos que repro-

ducen las revistas “La Comedia” y “Chateaubriand” dialo-

gan confortablemente con los Hans Peter Feldman de una

sala vecina, que reproducen las huellas de poetas, artistas y

escritores como Breton o Duchamp–; Javier Téllez –con un

video rodado con la participación de los enfermos del psi-

quiátrico de Mexicali en una marcha reivindicativa y festiva

y el lanzamiento de un hombre bala sobre la valla que sepa-

ra México y Estados Unidos; Wifredo Prieto –con una inter-

vención, una nube de alambradas que nos amenza desde el

techo de la sala, más contundente que otras que conozco

suyas–; y también otros, con obras fuera de Elsforth Terrace,

como Alexandre Arrechea o Manuel Ocampo.

El argumento de los co-comisarios de que no han

incluido artistas españoles porque «no [han] encontrado el

impulso de involucrarse con sinceridad y no solo ironía en los

temas sociales, que es la nota dominante en esta muestra»,

no sólo no me convence, sino que se ve a su vez discutido

por la selección que ellos mismo han hecho de la pieza de

Carlos Garaicoa o por la –que supongo impulsada por las

prisas– inclusión de varios artistas de una misma galería

chilena.

Me permito destacar otros cuya seducción es fun-

damentalmente estética y no derivada de lo convincen-

te o atractivo de sus argumentos sociales o políticos, así,

curiosamente los irlandeses Cleary + Connolly –con una

de las obras interactivas más sugerentes y sencillas de

las expuestas–, Jaki Irvine –con el video 56 Inch Fantasy,

que recorre el ir y venir arriba y abajo de los ascensores

del Guinnes Hops Store Visitors Centre en Dublin–, Matt

Calderwood –y sus construcciones tipo Tangram con una

escultura modular, cuya acción graba en vídeo y de la que

expone su precaria y fragil materialidad– y la pintora Mai-

read O’hEocha, con dos pequeños óleos sobre tabla que

compensan otras elecciones de pintores a mi juicio mucho

menos afortunadas.

JOTA CASTRO Us, 2011. Foto: Renato Ghiazza. Cortesía: el artista en colaboración con Gordon Ryan y NOJI, y Dublin Contemporary.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/artecontexton32-220304083126/85/Revista-Artecontexto-n32-85-320.jpg)