Revista Artecontexto n19

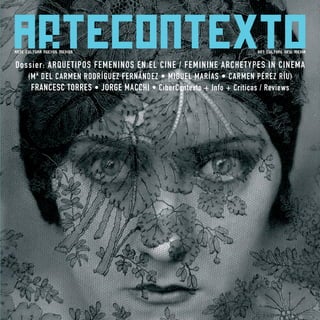

- 1. ARTECONTE X TO ARTE CULTURA NUEVOS MEDIOS - ART CULTURE NEW MEDIA Revista trimestral. Número 19 • Quarterly magazine. Issue 19 • España 18€ 19 ARTE CULTURA NUEVOS MEDIOS - 2008 / 3 ART CULTURE NEW MEDIA - 2008 / 3 ARTECONTE X TO ARTECONTEXTO ARTE CULTURA NUEVOS MEDIOS ART CULTURE NEW MEDIA ISSN 1697-2341 9 7 7 1 6 9 7 2 3 4 0 0 9 0 0 0 1 9 ISSN 1697-2341 9 7 7 1 6 9 7 2 3 4 0 0 9 0 0 0 1 9 Dossier: ARQUETIPOS FEMENINOS EN EL CINE / FEMININE ARCHETYPES IN CINEMA (Mª DEL CARMEN RODRÍGUEZ FERNÁNDEZ • MIGUEL MARÍAS • CARMEN PÉREZ RÍU) FRANCESC TORRES • JORGE MACCHI • CiberContexto + Info + Críticas / Reviews

- 2. Colaboran en este número / Contributors in this Issue: Mª del Carmen Rodríguez Fernández, Miguel Marías, Carmen Pérez Ríu, Juan Carlos Rego de la Torre, Alicia Murría, Eduardo Viñuela, Álvaro Rodríguez Fominaya, Clara Muñoz, Mónica Núñez Luis, Eva Grinstein, Agnaldo Farias, Filipa Oliveira, Gisela Leal, Uta M. Reindl, Alanna Lockward, Catalina Lozano, Kiki Mazzucchelli, Luis Francisco Pérez, José Ángel Artetxe, Suset Sánchez, Chema González, Alejandro Ratia, Eva Navarro, Mireia A. Puigventós, José Manuel Costa, Santiago B. Olmo, Pedro Medina, Natalia Maya Santacruz, Tamara Díaz, Miguel López, Javier Marroquí. ARTECONTEXTO ARTECONTEXTO arte cultura nuevos medios es una publicación trimestral de ARTEHOY Publicaciones y Gestión, S.L. Impreso en España por Técnicas Gráficas Forma Producción gráfica: El viajero / Eva Bonilla. Procograf S.L. ISSN: 1697-2341. Depósito legal: M-1968–2004 Todos los derechos reservados. Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida o transmitida por ningún medio sin el permiso escrito del editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any means without written permission from the publisher. © de la edición, ARTEHOY Publicaciones y Gestión, S.L. © de las imágenes, sus autores © de los textos, sus autores © de las traducciones, sus autores © de las reproducciones, VEGAP. Madrid 2008 Esta publicación es miembro de la Asociación de Revistas Culturales de España (ARCE) y de la Federación Iberoamericana de Revistas Culturales (FIRC) ARTECONTEXTO reúne diversos puntos de vista para activar el debate y no se identifica forzosamente con todas las opiniones de sus autores. ARTECONTEXTO does not necessarily share the opinions expressed by the authors. La editorial ARTEHOY Publicaciones y Gestión S.L., a los efectos previstos en el art. 32,1, párrafo segundo, del TRLPI se opone expresamente a que cualquiera de las páginas de ARTECONTEXTO sea utilizada para la realización de resúmenes de prensa. Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra sólo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Diríjase a CEDRO (Centro Español de Derechos Reprográficos: www.cedro.org) si necesita fotocopiar o escanear algún fragmento de esta obra. Editora y Directora / Director & Editor: Alicia Murría Coordinación en Latinoamérica Latin America Coordinators: Argentina: Eva Grinstein México: Bárbara Perea Equipo de Redacción / Editorial Staff: Alicia Murría, Natalia Maya Santacruz, Santiago B. Olmo. info@artecontexto.com Asistente editorial / Editorial Assistant: Natalia Maya Santacruz Directora de Publicidad / Advertising Director: Marta Sagarmínaga publicidad@artecontexto.com Directora de Relaciones Internacionales International Public Relations Manager: Elena Vecino Administración / Accounting Department: Carmen Villalba administracion@artecontexto.com Suscripciones / Subscriptions: Pablo D. Olmos suscripciones@artecontexto.com Distribución / Distribution: distribucion@artecontexto.com Oficinas / Office: Tel. + 34 913 656 596 C/ Santa Ana 14, 2º C. 28005 Madrid. ESPAÑA www.artecontexto.com Diseño / Design: Jacinto Martín El viajero: www.elviajero.org Traducciones / Translations: Joanna Porter y Juan Sebastián Cárdenas

- 3. Portada / Cover: EDWARD STEICHEN Gloria Swanson, New York, 1924 Copia positiva de plata en gelatina, positivada en 1961. 42,1 x 34,2 cm. Cortesía de The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 1924 Condè Nast Publications. Obra que forma parte de la exposición Edward Steichen. Una epopeya fotográfica. MNCARS. SUMARIO / INDEX / 19 5 Primera página / Page One: Mujeres y arquetipos / Women and Archetypes ALICIA MURRÍA Dossier Arquetipos femeninos en el cine clásico americano Feminine Archetypes in Classic American Cinema 7 Fantasías y miedos en el Hollywood clásico Fantasies and Fears in the Hollywood Classic Mª DEL CARMEN RODRÍGUEZ FERNÁNDEZ 16 Inocentes fatales, o fatal inocencia Fatal Innocents or Fatal Innocence MIGUEL MARÍAS 26 Perversas: La mujer malvada en el cine clásico Perverse: The Wicked Woman in Classic Cinema CARMEN PÉREZ RÍU 36 Francesc Torres. La memoria desnuda desciende una escalera Francesc Torres. Naked Memory Descending a Staircase JUAN CARLOS REGO DE LA TORRE 46 Jorge Macchi. Resignificaciones y azares Jorge Macchi. Resignifications and Fates ALICIA MURRÍA 54 CiberContexto EDUARDO VIÑUELA 58 Info 66 Criticas de exposiciones / Reviews

- 4. Women and Archetypes The phrase “a picture is worth a thousand words”, a cliché whose origins are lost in time, contained hints of a premonition. We live more in a world of images than of words, and increasingly our culture draws sustenance from an unceasing avalanche of visual information that grows at a dizzying pace. The currents of information are now multiplied globally, and with them the representations of the world. The power of images is overwhelming and, although every spectator if the 21st century considers himself to be a skilful reader of their contents, their power to be believed remains immense. Every image is a construction and belongs to a coded language and, for that same reason, is capable of deconstruction and decoding, and carrying out both these things from a critical plane becomes a necessary task. Much more than the photo, the moving image was and continues to be –although its distribution and consumption might have changed somewhat, substituting the dark projection room with television monitors, game consoles and Internet-- the most powerful medium for the showing and construction of collective imagery. Cinema soon realised its power as producer and transmitter of ideas and, now converted into an industry, it established itself as the most valuable purveyor of hegemonic values. The “factory of dreams” –and nightmares-- that Hollywood became with the Studio system, which controlled each and every stage of production and distribution, left little space for independent scriptwriters and directors. Women, who had an active presence in the origins of cinema –as would also occur with video-- were banished as creators and relegated exclusively to acting. Reflecting these conditions and in the context in which films were produced, Hollywood supported patriarchal values, and from the end of the 1920s and 1930s churned out impeccable and attractive products in which women acted out established roles and became the repositories of masculine fears. This brief commentary serves to introduce a dossier which addresses feminine representations and archetypes which have exerted fascination for decades and whose re-reading from a feminist perspective is presented by Carmen Rodríguez Fernández and Carmen Pérez Riu, along with Miguel Marías, who from the perspective of an unrepentant film buff ironically questions the readings which have been made over decades of a series of female characters traditionally defined as “femmes fatales”. ALICIA MURRÍA

- 5. Mujeres y arquetipos La frase “vale más una imagen que mil palabras”, siendo tópica y extraviado su origen en el tiempo, fuera éste cual fuera, contenía tintes premonitorios. Vivimos en un mundo de imágenes mucho más que de palabras, nuestra cultura se nutre cada día más de una avalancha incesante de información visual que crece y se acelera de manera imparable, los flujos de comunicación adquieren hoy alcance global multiplicando las representaciones del mundo. El poder de las imágenes resulta avasallador y, aunque todo receptor/espectador del siglo XXI se considere hábil lector de sus contenidos, su poder para actuar en un plano de verosimilitud sigue siendo inmenso. Toda imagen es construcción y pertenece a un lenguaje codificado y, por esa misma razón, es deconstruible y decodificable, y desarrollar ambos ejercicios desde un plano crítico se convierte en una tarea tan compleja como imprescindible. Mucho más que la fotografía, la imagen en movimiento ha sido y continúa siendo –aunque su distribución y consumo haya variado, sustituyendo la sala oscura de proyección por los canales de televisión, las consolas de juegos o Internet– el medio más poderoso de representación y de construcción de imaginarios colectivos. El cine supo muy pronto de su poder como productor y transmisor de ideas y, ya convertido en industria, se erigió en el más valioso difusor de los valores hegemónicos. La “fábrica de sueños” –y pesadillas– en que se convirtió Hollywood con el sistema de los Estudios, que controlaba todos y cada uno de los tramos de la producción y la distribución, dejaba pocas fisuras a la independencia de guionistas y directores. En cuanto a las mujeres, cuyo presencia fue activa en los orígenes del cine –lo mismo sucedería luego con el vídeo– quedaron, como creadoras, relegadas para ocupar exclusivamente el espacio de la actuación. Reflejo de las condiciones y el contexto en que se producen, las películas de Hollywood apuntalan los valores patriarcales y generan, desde finales de la década de los años 20 y 30, impecables y atractivos productos donde las mujeres ocupan los roles establecidos, o se convierten en depositarias de los miedos masculinos. Sirva este telegráfico comentario para introducir un dossier que aborda algunas representaciones y arquetipos de mujeres que han ejercido fascinación durante décadas y cuya relectura desde perspectivas feministas corre a cargo de Carmen Rodríguez Fernández y Carmen Pérez Riu, junto a ellas, Miguel Marías, desde su mirada de cinéfilo impenitente, cuestiona, con ironía, interpretaciones que a lo largo de décadas se han realizado sobre una serie de personajes femeninos definidos tradicionalmente como “mujeres fatales”. ALICIA MURRÍA

- 6. Retrato promocional de Greta Garbo para la película The Kiss (MGM, 1929), donde interpreta a la adúltera Irene.

- 7. La historia de Occidente se ha vertebrado a partir del pensamiento surgido de la filosofía griega y de la tradición judeocristiana, ejes de la construcción social de género, donde se puede hallar la respuesta a una ética que negaba todo principio de placer. La imagen de Eva como pecadora e incitadora al mal fue el argumento que se utilizó históricamente para hacer recaer sobre las mujeres la culpabilidad de la maldición bíblica. A esto hay que sumar la importancia que en la mitología pagana desempeñaron las representaciones de los mitos femeninos y el miedo ancestral de los hombres a sentirse presa de sus encantos, lo que provocó la necesidad de controlar a estas figuras míticas y poderosas que, en palabras de Erika Bornay: “simbolizaban la creencia de que si un hombre era seducido y poseído por una mujer, el resultado podía ser su muerte espiritual o física.”1 Estas creencias y mitos reforzaron la idea de que la mujer inducía al pecado y éste a la condenación eterna. De ahí, la polarización histórica de las mujeres en dos grandes grupos: el de las virtuosas y el de las pecadoras. Dicho de otro modo, el de las mujeres abnegadas y subordinadas a la ideología patriarcal, madres y esposas, seguidoras del ejemplo mariano, y el de las insumisas y transgresoras, mujeres que invaden el espacio masculino e intentan usurpar y subvertir su poder. Estas son las raíces de donde surge la asunción histórica de la inferioridad de la mujer y el origen de la tipología de personajes femeninos en el cine clásico americano. Los arquetipos de género en la cinematografía clásica de Hollywood nacen y se construyen como una consecuencia cultural del desarrollo del cine. Su evolución fue vertiginosa en la década de 1920 y culminó con la exhibición de la primera película sonora en 1927. Este hito constituyó una revolución que afectaba al cine en toda su extensión e implicaba importantes desembolsos de dinero por lo que, con el fin de rentabilizar la inversión y procurar una reducción de los costes en la adaptación al cine sonoro, en los primeros años de la década de 1930 se consolidó el Sistema de Estudios y el Star System. Este fue el origen de la especialización de las grandes empresas en géneros cinematográficos y de la contratación y pertenencia de todo el personal de la industria a unos Estudios determinados, incluyendo a directores, guionistas, actores y actrices. La consecuencia inmediata afectó a las grandes estrellas del cine, que comenzaron a ser conocidas por sus actuaciones en determinados papeles, contribuyendo así a la difusión de unos arquetipos de género.2 Por otra parte, para paliar el efecto que los diálogos pudieran ejercer en las mentes del público más “vulnerable”, se dispusieron una serie de normas, destinadas a proteger la moral. Estas medidas se recogieron, concretaron y publicaron en el Código de Censura Hays en los primeros años de la década de 1930. A decir verdad, ya en la etapa del cine mudo había comenzado una vigilancia cuidadosa por parte de algunos observadores. El cine, inventado en un principio como una atracción que mostraba imágenes en movimiento, había ido creciendo como un espectáculo de diversión, capaz de contar historias que potenciaban la imaginación de los espectadores que abarrotaban las salas. Fantasías en cierto modo contenidas al faltarles los diálogos, pero que, también por este motivo, dejaban al libre albedrío de la imaginación del público espectador la posibilidad de hacer lecturas sobre las que el sector más conservador DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 7 Mª DEL CARMEN RODRÍGUEZ FERNÁNDEZ* Arquetipos femeninos en el cine: Fantasías y miedos en el Hollywood clásico

- 8. 8 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER intentaba actuar celosamente. Los primeros moralistas aparecieron en 1907 llamando la atención del peligro de los Nickelodeon, donde las audiencias de niños e inmigrantes estaban expuestas a escenas de violencia y crimen, y donde podrían producirse conductas poco apropiadas entre los jóvenes asistentes al espectáculo. Los censores tenían también otras obsesiones en mente, ya que en la etapa de esplendor del cine mudo había nacido para la pantalla el personaje de la New Woman. Un concepto nuevo en cuanto que se salía de los patrones que representaban a la mujer como esposa y madre. La influencia que este modelo podía ejercer en las mentes de los más frágiles –según ellos, las mujeres, los inmigrantes y las personas jóvenes– constituyó un motivo más de preocupación para el patriarcado. La nueva mujer aparecía en las Serial Queen y en las comedias cortas bajo dos caracterizaciones principales. En la primera de ellas, en el papel de la joven que juega con la muerte y está inmersa en actuaciones difíciles salvando a los demás de todo tipo de situaciones comprometidas. En la segunda, como la joven irreverente que se ríe de sus guardianes, visita cabarets, flirtea con extraños y vuelve locos a los hombres a su alrededor. Hay que señalar que las películas con esta tipología femenina eran producidas también por mujeres, por lo que según Karen Ward Mahar, “Más que en ningún otro género de la era del cine mudo, los seriales y comedias cortas de la segunda década del s. XX sugieren que las mujeres que trabajaban en el cine, en su conjunto, contribuyeron a crear una visión alternativa del género en la pantalla.”3 La New Woman cinematográfica iba a tener una vida breve. En 1922, coincidiendo con la posguerra y con la época en la que la prensa comenzó a hacerse eco de la relación que podía existir entre el aumento de violencia en las calles y el thriller seriado, y a culpabilizar a directoras y productoras de las consecuencias que sus filmes podían tener entre el público, la National Association of the Motion Picture Industry (NAMPI) adoptó una serie de decisiones para limpiar la industria con la ayuda de una censura estatal o federal. Las productoras deberían refrenar las representaciones del sex appeal, la trata de blancas, los bajos mundos, la embriaguez, la drogadicción, la violencia gratuita y la mofa de las autoridades, así como aquellas escenas con actitudes, posturas y gesticulaciones vulgares. Esto supuso un largo paréntesis en la labor de difusión de estos nuevos modelos que las directoras y productoras llevaban a cabo en beneficio de las demás mujeres. La aparición de estos personajes excedía el límite de la corrección y subvertían el modelo de mujer hogareña y subordinada al varón que difundía la tradición patriarcal. Esta fractura, entre la imagen de la mujer sumisa y el espacio que las mujeres demandaban, alcanzó de lleno a las cineastas y supuso la casi desaparición de las directoras y productoras de la escena cinematográfica durante muchos años. Así pues, desde diferentes ángulos y por diversos motivos, a partir de 1930 se dieron las circunstancias socio económicas por las que a las mujeres se les cercenaban sus posibilidades interpretativas e iban a quedar reducidas a unos arquetipos que las objetualizaban y las limitaban como sujetos. Una vez más la ideología patriarcal actuaba como un rodillo, aplastando las iniciativas de las actrices al polarizarlas en los dos modelos de mujer que el pensamiento occidental se había encargado de propagar a lo largo de su historia: el ángel del hogar y el demonio. Esto que, según se acaba de exponer, parece consecuencia de una situación coyuntural, ahonda sus raíces en la dicotomización de roles que tan negativamente afectó a las mujeres, pues como señala Bram Dijkstra en Idols of Perversity: “[this] was a war largely fought on the battlefield of words and images”4 y que, efectivamente, en los comienzos del cine sonoro se convirtió en una batalla con las palabras y las imágenes como protagonistas. Los arquetipos tenían sus especificidades y las limitaciones interpretativas de las actrices remitían tanto a su potencial como a la falta de espacio social y escénico. Creados por y para difundir la Duel in the Sun [Duelo al sol] (Vanguard Films, 1947). Dirigida por King Vidor. Jennifer Jones en el papel de tentadora mestiza, cuya “desbocada” sexualidad la arrastra, junto a su amante, a la muerte.

- 9. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 9 ideología patriarcal, mantenían la dicotomía que tan persistentemente se había transmitido. Por una parte, están los modelos que representan a mujeres abnegadas, o poco inteligentes, o carentes de autoestima, o subordinadas a los hombres, o todo ello a la vez. En este primer grupo se enmarcan los personajes de mujeres ingenuas, casadas y madres de familia en su mayoría, y las mujeres minorizadas por cuestión de raza o etnia. Es decir, el arquetipo de la Cenicienta en el cine romántico, el de la esposa y madre sufriente en el melodrama, el de la rubia tonta y sexy en las películas protagonizadas por Marilyn Monroe, el de la novia de América en la comedia americana y el de la indígena racializada en los westerns, doblemente subyugada por cuestiones de raza y género. En contraposición a éstas, aparecen las caracterizaciones de personajes asertivos y fuertes, que no se doblegan a los deseos de los varones ni permanecen circunscritos a los espacios domésticos y que, en consecuencia, amenazan con adueñarse del espacio público: ya sean femmes fatales, perversas domésticas que alteran el orden natural de las cosas y subvierten la idea de hogar como espacio tranquilizador, o las que irrumpen en el espacio sexual masculino irritándoles y amenazándoles con un lenguaje gestual provocador. A estas últimas, los censores las consideran dañinas por la influencia que su representación en las pantallas ejerce sobre las demás mujeres y porquepuedensuponerundesequilibrioideológico, contrario a los intereses del patriarcado. Como dice Bornay: “La visión de un Hércules sometido a una Onfalia que le obliga a trabajar en labores propias del sexo femenino podría ser una imagen representativa del miedo, más o menos sutil, que se apoderó de muchos hombres de la época, temerosos ante la supuesta expectativa de verse subyugados por la New Woman.”5 Sin embargo, existían modos de escapar al férreo control del código Hays porque algunos textos presentan fisuras que permiten lecturas subversivas. Este es el caso del personaje de Laura en Breve encuentro (David Lean, 1946) de quien se puede decir que es una transgresora pasiva. Su historia de amor con un hombre casado no puede culminar, como sería su deseo, en una época de restringida moral. La película propone el final feliz al uso: Laura aparece sentada en el salón de su casa con su marido. Éste hace crucigramas mientras ella escucha música. La ambientación y los personajes destilan serenidad; no obstante, la escena es inquietante porque se adentra en los pensamientos de Laura, donde tiene cabida el adulterio y el deseo de poner fin a su vida, y constituye la fisura que permite al público espectador ser cómplice de su trasgresión. El personaje y la recreación de sus recuerdos muestran una resistencia al modelo social propuesto. Laura seguirá las normas de conducta que se esperan de ella como esposa y madre; pero nadie podrá poner coto a sus pensamientos, un territorio que sólo a ella corresponde. A partir de los años setenta, con la llegada de la teoría feminista Marlene Dietrich interpreta a la muy sofisticada aventurera Shanghai Lily en la película Shanghai Express (Paramount, 1932). Dirigida por Josef von Sternberg.

- 10. 10 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER aplicada al cine, se propusieron lecturas acerca de la naturaleza de la ideología, la importancia de la relación existente entre lo representado en la pantalla y el público espectador y las diferentes posibilidades de análisis de los textos. De entre todas, la de la británica Laura Mulvey6 se convirtió en paradigma al hablar de la interpelación que se crea entre director, actor y espectador masculino y las actrices y los personajes femeninos en la pantalla. Esta interpelación hace que la mirada sea voyeurística, narcisista y/o fetichista. La importancia del visor o de la cámara oscura, en la que se convierte la sala de cine, privilegia a los hombres en la contemplación de las imágenes porque les permite disfrutar de un espectáculo creado exclusivamente para ellos, convirtiéndoles en voyeurs. A su vez, lo representado en la pantalla y las relaciones ideológicamente construidas entre el personaje masculino y el femenino permiten al protagonista ostentar el privilegio de ser él, el sujeto deseante, quien lleve a cabo la acción del filme, mientras que la actriz tiene que conformarse con ser el objeto de ese deseo. Esto permite al espectador de la sala proyectarse en el actor y convertirse en una extensión del personaje masculino con lo cual se crea una relación narcisista entre ambos. En tercera instancia, el fetichismo surge por la necesidad de calmar la ansiedad de la castración que el hombre siente ante la figura femenina, de tal manera que deje de ser peligrosa para él y se convierta, por el contrario, en una figura tranquilizadora. Esto se logra fragmentándola y llamando la atención sobre partes concretas de su cuerpo, ya sea su mirada, sus hombros, su cuidada cabellera, ya sea identificándola con algún objeto o prenda de vestir de tal modo que llegue a trascender los límites de lo cinematográfico para integrarse en el imaginario colectivo. Esta desmembración permite controlar la amenazante figura de la mujer en las pantallas. Para las mujeres, la teoría feminista cinematográfica supuso un cambio fundamental en el modo de plantear y ver el cine. En el último tercio del siglo XX, gracias a la magnífica labor desempeñada por grupos de directoras cinematográficas, de directoras de festivales y de teóricas feministas, las directoras han retomado la cámara y surge una nueva manera de filmar, como alternativa temática y técnica al cine comercial, permitiendo a las mujeres articular y dar a conocer todo su potencial autoral e interpretativo, lejos ya de unos arquetipos construidos para difundir unos modelos sociales obsoletos. * Mª del Carmen Rodríguez Fernández es Profesora Titular de la Universidad de Oviedo, donde dirige el grupo de investigación Intermedia y Género. En la actualidad prepara Diccionario crítico de directoras europeas de cine. NOTAS 1. Bornay, Erika. Las hijas de Lilith. Madrid: Cátedra, 1998, p. 170. Remito la lectura de este libro al público interesado por profundizar en el tema de la mitología pagana y judeocristiana en la construcción de género. 2. Para una información detallada sobre diferentes arquetipos, consúltese la obra colectiva: Rodríguez Fernández, Mª del Carmen (Coord.). Diosas del celuloide. Arquetipos de género en el cine clásico. Madrid: Jaguar, 2007, donde se analiza su importancia a través de las actrices y los papeles a los que sus representaciones dieron lugar. 3. Ward Mahar, Karen. Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2006, p. 103. 4. Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. (Dijkstra, VII). 5. Bornay, Erika. Op. Cit., p.170, 83. 6. Explicar la teoría de la mirada excede la extensión de este texto, remito al lector interesado a consultar esta fuente: Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Other Narratives.” En Screen 16:3 (Autumn 1975), p. 6-18. De las reproducciones fotográficas nuestro agradecimiento a: Vanguard Films, Inc., Selznick Releasing Organization Manga Films S.L., Paramount Publix Corp. y EMKA LTD. Foto promocional de una jovencísima Marilyn Monroe en sus comienzos en Hollywood

- 11. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 11 Mª DEL CARMEN RODRÍGUEZ FERNÁNDEZ* Feminine Archetypes in Cinema: Fantasies and Fears in the Hollywood Classic Western history has been structured from Greek philosophical thought and the Jewish-Christian tradition, the driving forces of the social construction of gender, where one can find the response to an ethics that denied any pleasure principle. The image of Eve as sinner and provoker of evil was the argument which was historically used to place the blame for the biblical curse on women. To this must be added the importance given in pagan mythology to the representations of feminine myths and men’s ancestral fear of falling captive to women’s charms, which brought about the need to control these mythical and powerful figures who, as Erika Bornay said: “symbolized the belief that if a man was seduced and possessed by a woman, it could lead to his spiritual or physical death.”1 These beliefs and myths reinforced the idea that women induced men to sin and this to eternal damnation. From there, the historical polarisation of women into two large groups: that of the virtuous and that of the sinners. Expressed in another way, that of the selfless woman, subordinated to the patriarchal ideology, mothers, wives, followers of the Marian, and that of the rebellious and transgressors, women who invade the masculine space and try to usurp and subvert his power. It is from these roots that the assumption of women’s inferiority arose, and the origin of the types of women characters in classic American films. The gender archetypes in classic Hollywood film-making arose and were constructed as a cultural consequence of the development of the film industry. Its growth was dizzying in the 1920s and culminated in the showing of the first talking film in 1927. This achievement constituted a revolution which affected the entire range of films and involved the expenditure of a great deal of money so that, with the aim of making a profit on the investment in the adaptation to sound and of trying to reduce costs, the Studio System and the Star System was brought into being at the beginning of the 1930s. This was the origin of the specialisation of big companies in film genres and also of contracting personnel to work exclusively for specific studios, including directors, scriptwriters, actors and actresses. The immediate consequence of this affected the big film stars, who began to be known for their performances in certain roles, thus contributing to the diffusion of some gender archetypes.2 On the other hand, to lessen the effect that the dialogue might have on the more “vulnerable” minds in the audience, a series of regulations were put into force, intended to protect morals. These measures were brought together, summed up and published in the Hays Censorship Code at the beginning of the 1930s. In reality, even in the period of silent films a meticulous surveillance had begun to be carried out by observers. Films, invented originally as an attraction which showed images in movement, had gradually grown to become an entertainment, capable of recounting stories which fired the imagination of the audiences that packed the theatres. Restricted fantasies in some ways because they were lacking in dialogue, but, also for this reason, they left the imagination of the spectator free to interpret a field which was closely guarded by the most conservative sector. The first moralists appeared in 1907, calling attention to the danger of the nickelodeons, where audiences made up of children and immigrants were exposed to scenes of violence and crime, and where some of the young members of the audience might misbehave during the show.

- 12. 12 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER The censors also had other obsessions on their minds, for in the greatest period of splendour of silent films the New Woman screen character had emerged. A new concept in as much as it departed from thestandardrepresentationofwomenaswifeandmother.Theinfluence that this model could have on the more fragile minds –according to them, women, immigrants and the young, was yet another cause for worry for the patriarchy. The new woman appeared in Serial Queen and in short comedies in two main characters. In the first, in the role of the young girl who dices with death and is caught up in difficult actions getting everyone else out of dangerous situations. In the second, as the irreverent young women who laughs at her guardians, goes to cabarets, flirts with strangers and drives all the men around her crazy. It should be pointed out that the films of this feminine type were also produced by women, so that, according to Karen Ward Mahar, “more than any other genre of the silent era, the serial and short comedy of the 1910s suggests that women filmmakers, as a group, contributed to an alternative vision of gender on screen.”3 The New Woman films were to have a short life. In 1922, coinciding with the post-war period and with the time when the press was beginning to point out the link between the increase of violence on the streets and the thriller series, and to blame the female directors and producers for the consequences their films might have on the public, the National Association of the Motion Picture Industry (NAMPI) adopted a series of decisions aimed at cleaning up the industry with the aid of state and federal censorship. The producers had to refrain from scenes showing sex appeal, the white slave trade, the underworld, drunkenness, drug addiction, unnecessary violence and those mocking authority, as well as those scenes with vulgar attitudes, poses and gestures. This brought about a long parenthesis in the diffusion of these new models which female directors and producers had carried out to benefit other women. The appearance of these characters went beyond correct limits and transformed the model of the home-loving woman, dependent on the male who transmitted the patriarchal tradition. This break between the image of the submissive woman and the space that women demanded, reached film makers and led to the almost total disappearance of women directors and producers from the film world for many years, Thus, from different angles and for different reasons, after 1930 the social- economic conditions were such that women’s acting possibilities were limited and reduced to objectualising archetypes which limited them as subjects. Once again the patriarchal ideology acted as a steam roller, crushing actresses’ initiative by polarizing them in the two types of women that western thought had disseminated throughout its history: the angel of the home and the devil. This that, according to what has been shown, seems to be the result of a specific situation, has its roots deeply in the dichotomy of roles which affected women so negatively, for as Bram Dijkstra points out in Idols of Perversity: “[this] was a war largely fought on the battlefield of words and images”4 and which, in fact, at the beginning of talking films was a battle with the words and the images as protagonists. Archetypes had their specific needs and the acting limitations of the actresses’ revealed as much about their potential as to the lack of social and scenic space. Created by- and to spread- the patriarchal ideology, they maintained the dichotomy that had been so persistently transmitted. On the one hand, there are the models representing selfless, or not very intelligent women, women lacking in self-esteem, or those dependent on men, or all these things at the same time. In this first group are framed the characters of ingenuous women, married women and mothers for the most part, along with a minority of women of a different race or ethnic group. Which is to say, the archetype of the Cinderella in romantic films, the long-suffering wife and mother in melodramas, the silly, sexy blonde in the films starring Marilyn Monroe, the girlfriend of America in American comedies and the racialised native in westerns, doubly dominated because of her race and gender. In comparison to these are the assertive, strong characters, who don’t bow down to the wishes of the men nor do they remain tied down to the home and who, in consequence, threaten to take over public spaces: whether they be femmes fatales, domestic perverse women who alter the natural order of things and subvert the idea of the home as a soothing place, or women that erupt into the masculine sexual space irritating them and threatening them with a provocative body language. The censors considered this last group to be harmful because of the influence their acting on screen had on other women and because they could bring about an ideological imbalance, hostile to the interests of the patriarchy. As Bornay said: “the sight of a Hercules conquered by an Omphale who makes him do women’s work could be an image representing a more or less subtle fear, that took possession of many men of that time, fearful of the supposed prospect of seeing themselves dominated by the New Woman.”5 However, there were ways to escape the strict control of the Hays Code because some parts of the text had loopholes which allowed for subversive readings. This is the case of the character Laura in Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1946) whom we could say is a passive transgressor. Her love story with a married man cannot end as she would want, in a period of restricted morality. The film proposes an ordinary happy ending: Laura appears sitting in the parlour of her house with her husband. He is doing crosswords while she listens to music. The atmosphere and the characters exude serenity; however, the scene is disturbing because the film gets into Laura’s thoughts, where there is room for adultery and the desire to end her life, and constitutes the loophole which permits the audience to be an accomplice to her transgression. The character and the re-creation of her memories demonstrate resistance to the proposed social model. Laura will follow the rules of conduct that are expected of her as wife and mother, but nobody will be able to put a stop to her thoughts, a territory that only belongs to her. Starting from the 1970s, with the arrival of the feminist theory applied to films, readings were proposed concerning the nature of the ideology, the importance of the existing relationship between what is acted on the screen and the audience, and the different analysis possibilities of the texts. Of all of them, that of the British Laura Mulvey6 became the paradigm when talking about the interpellation that is

- 13. Marlene Dietrich in a portrait advertising the film Shanghai Express (Paramount, 1932). Directed by Josef von Sternberg.

- 14. 14 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER created between director, actor and male spectator and the actresses and the female characters on the screen. This interpellation makes the gaze seem voyeuristic, narcissist and/or fetishist. The importance of the visor or the camera obscura, in which the cinema is changed, favours men in the contemplation of images because it permits them to enjoy a show created exclusively for them, changing them into voyeurs. In its turn, what is performed on the screen and the relationships ideologically constructed between the male and female characters permits the protagonist to display the privilege of being himself, the wistful subject, who carries out the film’s action, while the actress has to conform with being the object of that desire. This permits the spectator in the cinema to project himself into the actor and make himself an extension of the male character, creating thus a narcissistic relationship between them both. In the third instance, the fetishism arises because of the need to calm the castration anxiety the man feels before the female figure, in such a way that she stops being dangerous to him and becomes, on the contrary, a soothing figure. This is achieved by fragmenting her and calling attention to certain parts of her body, whether it is her gaze, her shoulders, her well looked after hair, or identifying her with some object of article of clothing in such a way that she transcends the limits of the film to become part of the collective imagination. This dismembering allows the menacing figure of the woman on screen to be controlled. For women, the film feminist theory meant a basic change in the way of thinking about and seeing films. During the last third of the 20th century, thanks to the magnificent work by groups female film directors, festival directors and feminist theorists, women directors have taken up the camera again and a new way of filming has emerged, as a thematic and technical alternative to commercial films, which allows women to articulate and make known all their potential as authors and actresses, far from the archetypes constructed to spread obsolete social models. Marilyn Monroe, as a “loose” yet “redeemed” by love girl, in River of No Return (20th Century Fox, 1954). Directed by Otto Preminger. Marilyn as the irresistible girl-next-door in The Seven Year Itch (20th Century Fox, 1955). Directed by Billy Wilder.

- 15. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 15 * Mª del Carmen Rodríguez Fernández is a tenured professor at the University of Oviedo, where she directs the Gendered Intermedia research group. Currently she is preparing a critical dictionary of European female film directors. NOTES 1. Bornay, Erika. Lilith’s Daughters. Madrid: Cátedra, 1998, p. 170. I recommend this book to anyone interested in delving into the subject of pagan and Jewish-Christian mythology in the construction of gender. 2. For detailed information on different archetypes, consult the collective work: Rodríguez Fernández, Mª del Carmen (Coord.). Diosas del celuloide. Arquetipos de género en el cine clásico. Madrid: Jaguar, 2007, whereitsimportanceisanalysedthroughtheactresses and the roles spawned by their performances. 3. Ward Mahar, Karen. Women Filmmakers in Early Hollywood. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2006, p. 103. 4. Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. (Dijkstra, VII). 5. Bornay, Erika. Op. Cit., p.170, 83. 6. Explaining the theory of the gaze exceeds the extent of this article, I recommend that the interested reader consults this source: Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Other Narratives.” In Screen 16:3 (Autumn 1975), p. 6-18. We are grateful for the photographic reproductions to: Paramount Publix Corp. y EMKA LTD. 20th Century Fox Entertainment. Beckworth Corporation Production. Columbia Tri Star Home Entertainment. Rita Hayworth as an exotic man-eating gypsy in The Loves of Carmen (Columbia, 1948). Directed by Charles Vidor.

- 16. 16 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER Por causas que ignoro, y en contra de lo que parece ser la norma (al menos, así se cree o se dice a menudo), soy un cinéfilo muy escasamente mitómano. De hecho, ni siquiera comprendo el atractivo que ejercen ciertas mitologías ni la persistencia de algunos mitos, arraigados a base de su incesante repetición durante años e incluso décadas, pero que casi nunca resisten el análisis; la mayoría de estos tópicos, a veces legendarios, no tienen su base en las películas –casi siempre las mismas, y muy escasas: una muestra sesgada, en todo caso–, sino en la visión subjetiva de algún comentarista, asumida luego por otros, hasta sucesivas generaciones, con una fe digna de mejor causa y que se ciega a la evidencia, cuando no directamente generada y potenciada por la publicidad y el material de promoción (es instructivo ver los calificativos, deliberadamente difamatorios y sensacionalistas, dedicados en los respectivos trailers a dos encarnaciones ficticias de Rita Hayworth tan antitéticas como las de Gilda y Elsa Bannister en The Lady from Shanghai) . Dentro de un género tan nebulosamente definido que hasta sus creadores y más frecuentes practicantes –los norteamericanos– han tomado su nombre del francés noir (que aquí nos hemos limitado a traducir), se ha llegado a erigir como uno de sus rasgos fundamentales y constantes la omnipresencia de la llamada “mujer fatal”. Con independencia de que, efectivamente, en algunos casos aislados –un porcentaje no significativo de la producción etiquetada como “cine negro”– pueda resultar funesta para alguno (o incluso varios) de los protagonistas masculinos, si nos fijamos un poco observamos con cierta sorpresa, salvo que nos neguemos en redondo a admitir la prosaica verdad, que generalmente son ellos quienes se labraron su propia desdicha, que se la buscaron con ahínco, y que son contadas las mujeres que deliberada o malévolamente tendieron una trampa o trataron siquiera de seducir a los “primos” o fall guys que, por propia obsesión ciega, se dejaron subyugar por ellas, casi siempre más bien pasivas y hasta pacientes sufridoras de esa infatuación indeseada, o víctimas propiciatorias del complejo de protector/salvador que padecen muchos hombres a quienes gustaría poder ser “caballeros andantes” e ir por el mundo redimiendo a mujeres “perdidas”, rescatando prisioneras de otro (a menudo un maniático rico y poderoso) o simplemente a “damas” supuestamente “en apuros”. Un caso típico, sacado de una de las mejores (y más originales visualmente, a la par que argumentalmente canónicas) obras del género sería, sin duda, la hoy famosa y en su época menospreciada The Lady from Shanghai [La dama de Shanghai, 1947] de Orson Welles, con una Rita Hayworth despojada de su larga cabellera, teñida de rubia y cansinamente explotando en defensa propia (ante el protagonista, interpretado por el propio director, en la vida civil todavía, aunque por poco tiempo, su marido) su efectiva condición de víctima, como esposa de un abogado criminalista poco escrupuloso, mucho mayor que ella y completamente inválido, que al parecer la mantiene a su lado bajo chantaje y, se sospecha, como cebo para sus turbios negocios. Como al final, muerta ella y superviviente el desengañado Michael O’Hara, reconoce el autoproclamado “héroe”, INOCENTES FATALES, o FATAL INOCENCIA MIGUEL MARÍAS*

- 17. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 17 La ambiciosa Phyllis arrastra a Walter al asesinato y al desastre pero también ella, faltaría más, recibe su castigo. Double Indemnity [Perdición] (Paramount, 1944). Dirigida por Billy Wilder. Rita Hayworth, malvada irresistible en The Lady from Shanghai [La dama de Shangai] (Columbia, 1947). Dirigida por Orson Welles

- 18. 18 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER él mismo se lo buscó. Nada como la prodigiosa primera secuencia de la película para evidenciarlo, y para que no quede la menor duda lo deja bien claro la voz interior, retrospectiva, de Welles, que se presenta proclamando “Cuando empiezo a comportarme como un tonto pocas cosas pueden detenerme... Desde el día que la conocí no estuve del todo en mis cabales durante suficiente tiempo...”. Una historia paralela es la que cuenta una película que no se etiqueta como perteneciente al género, aunque tenga con él más puntos de contacto que algunos de los reputados “clásicos” del mismo: Vertigo [De entre los muertos], 1958, de Alfred Hitchcock, que podría describirse, esquemáticamente como la combinación de un film “negro”, Laura (1944) de Otto Preminger, y un melodrama anterior del propio Hitchcock, Rebecca (1940) . Si buscamos la raíz del mito, la plataforma de apoyo inicialmente encontrada por algunos comentaristas, sobre todo franceses, habremos de remontarnos a la tercera y más famosa versión, por fin homónima, de la novela de Dashiell Hammett The Maltese Falcon [El halcón maltés], escrita (es un decir) y dirigida por John Huston en 1941, es decir, en los albores del “cine negro”, y a su protagonista, la nada frágil, poco de fiar y escasamente seductora Mary Astor, por la que un muy ingenuo Sam Spade (Bogart) se deja engañar para luego descubrir que era la fría calculadora ambiciosa que cualquier espectador medianamente avispado sospechó a simple vista y desde su primera aparición, en uno de esos casos en que la elección de actores hace imposible la ambigüedad perfectamente sostenible en la novela. El trato que recibe de Bogart al final no puede ser más despegado y miserable, sin duda producto más del despecho y de la irritación consigo mismo que de ningún afán justiciero o incluso vengativo. Sin embargo, algo debió hacer vibrar a los misóginos, que convirtieron a Mary Astor en paradigma de la mujer malvada del film “negro”. Debo confesar que las guapas heroínas del cine negro –por definición, si han de ser condenadas, morenas, y contrapuestas a alguna rubia sosilla y simplemente mona– siempre me han caído bien. Aparte de ser a menudo auténticas bellezas –como Ava Gardner– o, cuando menos, “extrañamente atractivas” o misteriosas, lo que inevitablemente despierta y retiene duraderamente la curiosidad, Jane Greer interpreta en Out of the Past [Retorno al pasado] (RKO, 1947) a una de las grandes pérfidas de la historia del cine, que lleva a la muerte al, relativamente, buen chico. Dirigida por Jacques Tourneur.

- 19. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 19 las he visto acusadas (en la pantalla y fuera de ella) de intenciones que parecen del todo ajenas a las que pudieran albergar, de tener realmente alguna, lo que tampoco era sistemáticamente el caso; a menudo, se veían obligadas a improvisar sobre la marcha, a abrazarse a esa oportunidad que pintan calva, para escapar de un destino más aburrido que la muerte. Normalmente, y descontando las excepciones que se han convertido en supuesta regla, estas mujeres son meras “perchas” (a ser posible “inaccesibles”, desde casadas a “dominadas” por otros, desde neuróticas, enfermas o locas hasta ya muertas) en las que algunos hombres más bien frustrados, soñadores y maniáticos han colgado sus ideales teóricos, sin reparar en que las virtudes (y los defectos) que atribuían a estas mujeres casi siempre, al menos en un alto porcentaje, eran de su propia cosecha, sin que ellas hicieran otra cosa que vivir, ser, estar, pasar por allí o tener la mala fortuna de cruzarse con ellos y verse, a menudo, perseguidas, acosadas o atrapadas por ese pretendiente indeseado y posesivo que acababa desarrollando por ellas una fijación enfermiza y obsesiva, muchas veces agobiante, incluso cuando la guiaban o alimentaban las más altruistas y generosas intenciones. Hay que reconocer que esa tentación, mezcla de redentorismo, complejo de superioridad e inconsciente narcisismo, también afecta a bastantes mujeres, no menos empeñadas en cambiar “por su propio bien” al hombre elegido como destinatario de sus atenciones, mimos y cuidados, y a quienes, con el intervencionismo igualmente bondadoso de una madre dominante o de un misionero en tierras paganas, tratan de corregir, convertir o salvar de su propensión a la violencia o a la vagancia, de su afición al juego o la propiedad ajena, de las variadas dipsomanías que enajenaban al hombre elegido o que se les había puesto a tiro… Pero como hasta la fecha las mujeres han estado en una posición de inferioridad legal e institucional ante los hombres,solíansermásdiplomáticas,suavesyastutasensuscruzadas reformistas que los hombres, lo que hace que estadísticamente, tanto en el cine como en la vida real, sean más a menudo víctimas que verdugos, lo que ya sería una circunstancia atenuante, si no eximente, para cualquier tentativa de fuga o liberación, incluso con empleo The Big Sleep [El sueño eterno] (Warner Bros, 1946). Lauren Bacall no estuvo dispuesta a ser tan malvada en la película como la protagonista de la novela de Raymond Chandler. Dirigida por Howard Hawks. ,

- 20. 20 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER de venenos, accidentes simulados o, mucho más raramente, armas blancas o de fuego. Por cada Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck, que se convirtió a partir de cierta edad en un arquetipo de “mala” mujer amargada y con un resto de vitalidad oprimida francamente peligroso) en Double Indemnity (1944), de Billy Wilder, hay varias que podrían justificar, siquiera hasta cierto punto, su conducta traicionera o intrigante, como Elsa Bannister –según se revela al final, súbita y atropelladamente, aunque nada vemos de cuanto se le imputa, ni queda muy claro y, en todo caso, su supuesto plan sería tan confuso y retorcido como improbablemente eficaz, por lo que no puede extrañar su total fracaso– en The Lady from Shanghai. Ysonmásnumerosasenelgénerolasinjustamentedesacreditadas –como la malfamada y escandalosa Gilda, sin ir más lejos, la pobre, casi el único personaje decente y leal de la película, sumamente turbia y, aunque escrita por mujeres, de una atmósfera irrespirablemente misógina– e incluso, si se me apura, las amorosamente sacrificadas por seguir a su amado (desde la Sylvia Sydney de You Only Live Once, 1937, de Fritz Lang, hasta la Cathy O’Donnell de They Live by Night, 1947, de Nicholas Ray, pasando por la Ida Lupino de High Sierra, 1941, de Raoul Walsh). Incluso me parece una exageración (como poco) irresponsable calificar de “fatales” a simples mujeres guapas, a menudo más jóvenes que sus aburridos maridos o “patrocinadores” –sean delincuentes, alcohólicos, celosos, probos trabajadores agrícolas o agobiados tenderos–, y sin afición a las labores del hogar, que se sienten frustradas en una vida sin diversiones ni colorido, monótona y rutinaria, sórdida y tacaña, en la que se ajarán aceleradamente hasta perder su atractivo y su frescura, y propensas, por tanto, a dejarse tentar y camelar por cualquier advenedizo irresponsable y chulo, con más marcha y más labia, que esté dispuesto a seducirlas con promesas de una vida más estimulante y a reclutarlas como ayudantes para hacerse con el capitalito o los ahorros del marido o sucedáneo. Esto es lo que le ocurre a esa gran mayoría –bien distantes de Lady Macbeth– que, en lugar de urdir tramas criminales en las que utilizan como meros peones ejecutores a los hombres (de los que piensan librarse cuanto antes), lejos de tener ambiciones monetarias desmedidas (algo de arribismo sí que hay, pero ¿quién no quiere mejorar su nivel o tren de vida?), sin necesidad de fingir sentimientos radicalmente insinceros para subyugar a sus ilusos enamorados; a lo sumo, se dejan querer durante una temporada, o ponen como obstáculo insalvable al marido para hacer más urgente e ineludible su eliminación. Son, en el fondo, si no siempre víctimas previas de sus víctimas prospectivas, sí al menos rehenes de su origen familiar y social, de las pasiones arrebatadas que inspira su belleza, de la incomprensión, o de otros engaños y promesas no cumplidas. Así, por ejemplo, casi todos los personajes encarnados por Ava Gardner en las películas de Robert Siodmak de los años 40, algunos de los retratados por Joan Bennett, tanto con Fritz Lang como con Jean Renoir, o el ejemplo tardío pero trasparente de Debra Paget en The River’s Edge [Al borde del río], 1957, de Allan Dwan, son ciertamente más usuales que las arpías codiciosas y gélidas que le tocó desempeñar a Angie Dickinson en la versión de The Killers [Código del hampa], 1964, de Don Siegel o en Point Blank [A quemarropa], 1967, de John Boorman. En realidad, podría decirse que casi todas la mujeres del cine negro lo que son es inocentes. Unas por edad o falta de experiencia de otras formas de vida algo menos simples que la que les ha caído en (mala) suerte, otras por poca inteligencia o educación insuficiente, otras por carácter o bondad natural o impuesta a base de lecturas bíblicas y ejemplos escarmentadores, otras por rebeldía simplista y primaria, casi todas son, en el fondo, más que otra cosa, ingenuas e inocentes. Y esa misma inocencia es parte de la atracción que ejercen sobre quienes desean poder sentirse seguros de ser más listos y de controlarlas y dominarlas. En eso sí que ellos son “fatales”. Pero, sobre todo, para ellas. * Miguel Marías se define como “un aficionado al cine que escribe”. De las reproducciones fotográficas nuestro agradecimiento a: Columbia Tri Star Home Entertainment RKO – Manga Films S.L. Turner Entertainment Co. y Warner Home Video. Rita Hayworth y Orson Welles en un descanso de La dama de Shangai.

- 21. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 21 For reasons which I cannot fathom, and in contrast to what seems to be the norm (at least that is what is often believed or claimed), I am not a very mythomaniac film fan. In fact, I cannot even understand the attraction exerted by certain mythologies or the persistence of some myths, which have taken root thanks to their incessant repetition over the years, sometimes even over decades, but which almost never withstand analysis; most of these topics, some of which are legendary, do not have a basis in film –only a few of them do, and it is almost always the same ones: an oblique sample, in any case–, and instead are founded in the subjective vision of some commentator, later taken on by others, generation after generation, with a faith more suited to a better cause, and one which is blind to evidence, when not directly generated and driven by advertising and promotional materials (it is enlightening to see the deliberately sensationalist and defamatory epithets applied to each of the trailers to two such antithetical fictitious incarnations of Rita Hayworth in Gilda and Elsa Bannister in The Lady from Shanghai) . Within a genre which is so nebulously defined that even its creators and most frequent practitioners –the North Americans– have taken its name from the French noir (which here we have simply translated), the omnipresence of the so-called “femme fatale” has been established as one of its basic and constant features. Independently of the fact that in some isolated cases –an insignificant percentage of the production labelled “film noir”– it can be unfortunate for some (or even various) of the male leads, if we focus on this a little we are somewhat surprised to see, unless we completely refuse to admit the prosaic truth, that generally it is they themselves who brought about their own misery, that they earnestly look for it, and there were few women who deliberately and maliciously laid a trap or even tried to seduce the fall guys who, in their blind obsession, were enslaved by the women, almost always passive and even patient sufferers of that unwanted infatuation, and scapegoats of the protector/saviour complex that afflicts many men who would like to be “knight errants” and go through life redeeming “lost” women, rescuing those women supposedly in “distress”, imprisoned by another (often a rich and powerful eccentric). A typical case, taken from one of the best (and visually most original, and at the same time canonical plotwise) of the genre would be, without doubt, the now famous and in its time underrated The Lady from Shanghai, 1947, by Orson Welles, with a Rita Hayworth stripped of her long head of hair, bleached blonde and listlessly exploiting, in self defence, (before the main character, played by the director himself, in civil life still her husband, although not for much longer) her effective condition of victim, as the wife of a not very scrupulous criminal lawyer, much older than she and a helpless invalid, who seems to use blackmail to keep her at his side and, one suspects, to use her as bait in his shady deals. As at the end, with her dead and the disenchanted Michael O’Hara surviving, the self-proclaimed “hero” acknowledges, he went looking for it himself. There is nothing like the wonderful first sequence of the film to make this clear, and any MIGUEL MARÍAS* FATAL INNOCENTS or FATAL INNOCENCE

- 22. remaining shadow of doubt is eradicated by the interior retrospective voice of Orson Welles, who is presented proclaiming “When I start acting like a fool not much can stop me... Since the day I met her I wasn’t quite in my right mind for enough time...”. A parallel story is that which is recounted by a film which is not labelled as belonging to the genre, although it has more things in common with it than some of the respected “classics” themselves: Vertigo, 1958, by Alfred Hitchcock, that could be described schematically as the combination of a film noir, Laura (1944) by Otto Preminger, and an earlier Hitchcock melodrama, Rebecca (1940) . If we search for the roots of the myth, the support platform initially found by some commentators, especially the French, we will have to go to the third and most famous version, finally of the same title, of the novel by Dashiell Hammett The Maltese Falcon, written (so to speak) and directed by John Huston in 1941, that is to say, at the dawn of film noir, and its star, the anything but fragile, unreliable and not very seductive Mary Astor, whom the very ingenuous Sam Spade (Bogart) fell for, only to discover later that she was the cold, calculating and ambitious woman that every half awake spectator had suspected from the very beginning, in one of those cases in which the choice of actors makes it impossible to depict the ambiguity which is perfectly sustainable in the novel. The treatment she receives from Bogart at the end could not be more detached and miserable, undoubtedly resulting more from spite and irritation with himself than any desire for justice or vengeance. However, something must have made the misogynists excited for them to have changed Mary Astor into the paradigm of the wicked woman of film noir. I have to confess that I have always liked the beautiful heroines of film noir –by definition, if they have to be condemned, dark and the opposite of some vapid and simply pretty blonde Apart from often being really beautiful –like Ava Gardner– or, at least, “strangely attractive” or mysterious, which inevitably awakens and lastingly retains my curiosity, I have seen them accused (both on and off screen) of intentions that seem totally unlike those they could entertain, if they really had any, which was not systematically the case; often they found themselves obliged to improvise as they went, to embrace that opportunity that seems impossible, to escape from a fate more boring than death. Normally, and discounting the exceptions that that have become the supposed rule, these women are merely “hangers”, (and, if possible, “inaccessible, from married women to women “dominated” by others, from neurotic, sick or crazy women to those already dead) on which some frustrated, obsessed and dreamy men have hung their theoretical ideals, without paying attention to the fact that the virtues (and the defects) that they attribute to these women are almost always, at least in a high percentage of cases, of their own making, without the women doing anything more than live, be, go about their business and have the bad luck to run up against them and see themselves often pursued, hounded and trapped by that unwanted and possessive suitor, who ended by developing a sickly and obsessive fixation on the woman, which was often oppressive even when it was guided and nourished by the most altruistic and generous intentions. It has to be admitted that this temptation, a mixture of redemptionism, superiority complex and unconscious narcissism, also affects quite a few women, no less determined to change “for his own good” the man chosen as the recipient of their attention, pampering and care, and those, with the equally kind-hearted interfering manner of a domineering mother or a missionary in pagan lands, tries to correct, convert or save the man that had taken their fancy from his propensity to violence or idleness, from his love of gambling or other men’s property, and the different dipsomanias that drove him mad. But as, until now, women have been in a position of legal and institutional inferiority with regard to men, they were usually more diplomatic, mild and astute in their reformist crusades than the men, which means that statistically, both in films and in real life, they are more often victims than executioners, which would be an extenuating, if not grounds for exemption, circumstance, in any attempt at flight or liberation, even with the use of poison, fake accidents or, much rarer, knives or guns. For every Martha Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), that, after a certain age, became the archetype of the bitter “bad” women with a trace of a frankly dangerous oppressed vitality, in Double Indemnity (1944) by Billy Wilder there are several that could justify, up to a point at least, their treacherous or scheming conduct, such as Elsa Bannister –from what is suddenly and hastily revealed at the end, although we see nothing and neither is it made clear what she is charged with, and anyway her supposed plan would be so confused and twisted as to be most probably ineffective, so her complete failure is not to be wondered at –in The Lady from Shanghai. In the genre there are many cases of unjustly slandered women –like the infamous and scandalous Gilda, to look no farther, the poor, almost the only decent and loyal character in the film, extremely troubled and, although written by women, with an unbreathably misogynous ambience– and even, if I am hurried, the lovingly sacrificed for following their beloved (from Sylvia Sydney in You Only Live Once, 1937, by Fritz Lang to Cathy O’Donnell in They Live by Night, 1947, by Nicholas Ray, and including Ida Lupino in High Sierra, 1941, by Raoul Walsh). It even seems an irresponsible (at least) exaggeration to me to describe as femme fatales ordinary beautiful women, often younger than their boring husbands or “financial supporters” –whether they be delinquents, alcoholics, jealous, poor agricultural workers or worn-out shopkeepers–, and with no love of housekeeping, who feel frustrated by a life without amusements, colourless, monotonous and humdrum, sordid and mean, in which they will rapidly be crushed until they loose their attractiveness and freshness, and therefore disposed to be tempted by any irresponsible, cocky outsider, with more get-up and- go and glibness, who is disposed to seduce them with promises of a more stimulating life and recruit them as an accomplice to getting hold of the husband’s or protector’s small capital and savings. This is what happens to that great majority –a long way from Lady Macbeth– who, instead of plotting criminal schemes in which they use men like mere pawns to carry out their plans (and whom they plan to drop as soon as possible), far from having boundless monetary ambitions (there is something of upward mobility, but who doesn’t want 22 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER

- 23. Gilda (Columbia, 1946), an apparent libertine, turned icon of classic cinema. Directed by Charles Vidor

- 24. 24 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER to go up in the world and improve their lifestyle?), without the need to fake strong feelings to dominate their deluded lovers; at the most, they allow themselves to be loved for a time, and make the husband an impossible obstacle in order to make his elimination more urgent and unavoidable. At heart, they are, if not always victims prior to the prospective victims, at least hostages to their family and social origins, of the impetuous passions their beauty inspires, of incomprehension, and of other deceits and unkempt promises. So, for example, are almost all the characters played by Ava Gardner in Robert Siodmak’s films in the 1940s, some of those portrayed by Joan Bennett, with both Fritz Lang and Jean Renoir, or the late but transparent example of Debra Paget in The River’s Edge, 1957, by Allan Dwan, really more usual than the greedy and icy harpies played by Angie Dickinson in the version of The Killers, 1964, by Don Siegel or in Point Blank, 1967, by John Boorman. In reality, it could be said that almost the women in film noir are innocents. Some because of their age and lack of experience of other ways of life slightly less simple than they are used to, others because of low intelligence or insufficient education, others because of their character or good nature, whether natural or imposed by bible readings or deterring examples, others because of simplistic and primary rebellion, at heart almost all of them are more ingenuous and innocent than anything else. And this same innocence is part of the attraction that they exert over those who want to feel sure of being smarter and be able to control and dominate them. In this they are certainly “fatal”. But, above all, for the women. * Miguel Marías defines himself as “a film fan who writes”. We are grateful for the photographic reproductions to: Columbia Tri Star Home Entertainment, Sony Pictures, Turner Entertainment Co. y Warner Home Video. Out of the Past (RKO, 1947). Jane Greer plays one of the evil women par excellence in classic Hollywood cinema. Directed by Jacques Tourneur.

- 25. Laura Bacall, with the look of a “femme fatale” in a photo promoting the film The Big Sleep (Warner Bros,1946). Directed by Howard Hawks.

- 26. 26 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER CARMEN PÉREZ RÍU* “Si hubiera sabido cómo iba a acabar todo, me habría detenido en el comienzo. Es decir, si hubiera estado en mi sano juicio. Pero en cuanto la vi,… en cuanto la vi, mi sano juicio se esfumó por un tiempo” Michael O’Hara en La Dama de Shangai La maldad, como subraya Vicente Domínguez, ha sido desde siempre objeto de atención de todas las artes, que “han insistido una y otra vez en trazar el rostro del mal, en producir imágenes del mal”1 . Inscrita en la mitología de los orígenes de nuestra cultura2 , la asociación de la mujer con la maldad se puede considerar uno de los pilares de la misoginia, articulada como la necesidad de mantener controladas a las mujeres. Entre los tipos de maldad femenina del cine clásico destacaremos tres: las femme noire (La dama de Shangai, Gilda, Perdición), a quienes Ann Kaplan describe como “mujeres definidas por su sexualidad, que se muestran deseables pero peligrosas para los hombres”3 . Atrapadas, por codicia, en un matrimonio con un hombre a quien desprecian, utilizarán su capacidad de seducción para servirse de un segundo hombre como instrumento y escapar a su control; la rival (Eva al desnudo), epítome de la deslealtad de las mujeres, incluso con aquellos a quienes han profesado devoción; la transgresora (Las tres caras de Eva, Jezabel), empecinada en desafiar las normas de comportamiento prescritas de maneras que pueden llegar a ser letales. La fascinación del cine clásico de Hollywood por la mujer malvada dio lugar a personajes femeninos fuertes, cuya participación en la trama aumentaba la riqueza de la construcción psicológica, también de los personajes masculinos. Estas “damas”, de Hollywood, como llamó el escritor Ian Cameron a las actrices que las interpretaron4 , crearon mitos cinematográficos: estrellas, como Bette Davis y Rita Hayworth, cuyas vidas se confundieron con sus personajes. Uno de los eslóganes promocionales de Gilda subrayaba “¡Nunca existió una mujer como Gilda!” y la hermosa imagen de Hayworth, enfundada en su vestido negro es el icono visual por excelencia de la mujer fatal en el cine5 . No, nunca existió una mujer como Gilda porque se trata en realidad de una fantasía masculina6 para conjurar la amenaza que supone la sexualidad femenina fuera de su control: “Ser dueña de su sexualidad es algo que le da a la mujer una insólita autonomía dramática. Y también un insólito poder: en los argumentos del cine negro, la femme noire amenaza la vida del hombre pero lo que representa realmente es una amenaza para su ego”7 . El análisis que Lucy Fischer hace de La Dama de Shangai destaca los elementos míticos que pueblan el filme8 . El yate en el que viajan los Bannister se llama Circe, como la hechicera de la Odisea que convierte a los hombres en animales; Hayworth canta sobre la proa a modo de sirena, para embrujar al navegante representado por Orson Welles, que se le resiste con tenaz empeño durante más de dos tercios del filme. Elsa Bannister es una esfinge, el enigma femenino por excelencia, pronta a devorar a los hombres que no logren resolver el acertijo que plantea. La mujer malvada constituye un mito, no sólo porque su comportamiento escape al control masculino dentro de la trama, sino Perversas: La mujer malvada en el cine clásico

- 27. DOSSIER · ARTECONTEXTO · 27 porque se escapa a su conocimiento. El protagonista puede cosificar a la mujer con su mirada, imponerse y dominarla, puede incluso destruirla, pero no llega nunca a comprenderla. Según la premisa de Laura Mulvey, la exhibición de la sensualidad de la femme noire hace accesible a la mujer para el espectáculo voyeurista 9 –el personaje de Glenn Anders en La Dama de Shangai observa a Hayworth lascivamente a través de un catalejo mientras ella toma el sol; y Barbara Stanwick se presenta escasamente envuelta en una toalla la primera vez que se encuentra con Fred MacMurray en Perdición– pero también supone su denuncia como depredadora sexual y en este rol la trama clásica evoluciona indefectiblemente hacia un final que constituye su castigo y control (Gilda) o su total destrucción (La Dama de Shangai, Perdición). En las películas que hemos destacado, las perversas no sólo son miradas por personajes masculinos, también son narradas por ellos10 . La voz que inicia y focaliza el relato es la voz de un hombre que se configura como una especie de anti-héroe, aparentemente ordinario, posiblemente anodino (un marinero a sueldo, un convencional vendedor de seguros, o el perdedor venido a menos que es Johny Farrell –Glen Ford– al comienzo de Gilda) alguien que puede por lo tanto representar colectivamente a “el hombre común”. La principal característica de esa voz es su cinismo: Johny Farrell (Glenn Ford) afirma que “las estadísticas dicen que hay más mujeres en el mundo que ninguna otra cosa. Excepto insectos”. Michael O’Hara (Orson Welles) “La única manera de no meterse en líos es dedicarse a envejecer y nada más”; Walter Neff (McMurray) ironiza sobre el asesinato, que en aquella calle “huele a madreselva”. Otra característica común a todos ellos es el hecho de que se declaren atrapados en el laberinto de la mujer, tratando de desvelar su enigma. Inician esta empresa creyéndose a salvo, la terminan con cinismo. Algo parecido sucede en Las tres caras de Eva, donde el narrador masculino es un psiquiatra que presenta a los posibles espectadores La famosa escena de los espejos de la película The Lady from Shanghai [La dama de Shangai] (Columbia, 1947). Dirigida por Orson Welles.

- 28. 28 · ARTECONTEXTO · DOSSIER incrédulos el espinoso asunto de la doble personalidad; o en Eva al desnudo, en la que el narrador, George Sanders, es un descreído y agudo crítico teatral. Todos ellos, cada uno en su estilo, narran la historia en flashback, y la premisa común es que, una vez han finalizado lo sucesos, aún sin comprenderlos plenamente, han adquirido un conocimiento sobre el enigma de la mujer –“Ya les hablaré de Eva”, dice Sanders con sorna, “les contaré todo acerca de Eva”– en una extraña pérdida de la inocencia con la que ellos mismos y/o otros personajes se acercaron a ella inicialmente. Con el ego destruido ofrecen este conocimiento al espectador masculino, estableciendo una sombría complicidad con él para ponerle en guardia contra el peligro de sublimar a la mujer. En cuanto a la espectadora, los dos caminos que le permite su posibilidad de identificación múltiple –con el héroe y su forma de narrar los hechos o con la mascarada de la mujer malvada11 , es decir, brevemente con su belleza y su exhibición de feminidad, y masoquistamente con su destrucción– llevan realmente al mismo lugar: a la misma advertencia sobre el fin que le aguarda a la mujer que trata de controlar al hombre con seducción. La maldad en la mujer convive muchas veces dentro del mismo film con comportamientos de los personajes masculinos que incluyen crueldad verbal (Bannister, marido de Hayworth en La dama de Shangai, o el personaje de George Brent en Jezabel), la violencia doméstica de David Wayne, que interpreta al esposo de Eva White en Las tres caras de Eva y le dice “Eso se merece una bofetada” cuando descubre que ella ha gastado más de doscientos dólares en bonitos vestidos y luego la amenaza de muerte (eso sí, después de que ella haya tratado de estrangular a la hija de ambos). Recursos a la violencia física son frecuentes actitudes de los hombres en estas películas como medios de establecer o mantener el poder (la bofetada de Gilda, y también, aunque es menos mencionada, la que recibe Rita Hayworth de su ya ex-marido Orson Welles, en La Dama de Shangai, o el uso de armas, matones, palizas, etc.) y diferentes grados de delincuencia. Como aduce José Antono Hurtado, la concentración de malos por fotograma es mayor en el cine negro que en ningún otro género12 . Observadas detenidamente, las manifestaciones del mal de las mujeres en estos filmes toman formas propias de los débiles: la maquinación, la incitación a cometer un crimen, la seducción como fórmula para acceso al poder, la conducta casquivana como amenaza al orden social y económico representado por la unidad familiar, la mentira o la ocultación, la resistencia activa o pasiva a ser controlada, el engaño (especialmente la apariencia de estar desvalida o la candidez fingida). Sus actividades amenazan con desestabilizar el orden impuesto por los personajes masculinos en su entorno y por eso resultan peligrosas. Si un criminal poderoso, como Ballin Mundson (George MacReady) en Gilda, o un abogado de éxito, pero físicamente impedido, en La dama de Shangai, se casa con una mujer hermosa (Rita Hayworth) es para que ella le sirva de adorno, de trofeo y engrandezca su imagen también en el plano sexual. La transgresión por parte de la esposa abre una grieta en su capacidad de imponer el control, que podrían aprovechar sus enemigos y acólitos para cuestionarlo también en nombre propio. La sugerente insinuación que Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) deja caer en Perdición despierta no sólo el deseo sexual sino también la codicia de Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), de modo que será él quien planee cada uno de los detalles y ejecute con toda precisión el asesinato del marido. Es curioso observar que ella nunca le pide que lo haga. Algo similar ocurre en Jezabel, donde la caprichosa heredera interpretada por Bette Davis es la única capaz de menoscabar las influencias de su prometido (Henry Fonda), que verá su buen nombre en la picota cuando ella se viste con un escandaloso traje rojo para la fiesta de debutantes. El nombre que da título a la película, Jezabel, “una mujer mala” se lo da su tía, escandalizada cuando ve que sus maquinaciones incluyen inducir a su amigo Buck (George Brent) a enfrentarse en duelo a muerte por ella. Una vez se ha demostrado su disposición a la rebeldía y su capacidad para el mal, el comportamiento de la mujer malvada es impredecible. La incertidumbre sobre las decisiones que ella tome se convierte en el principal centro de interés narrativo y una impagable fuente de suspense. Las implicaciones psicológicas de la mujer malvada se subrayan en su construcción visual. Se ha descrito a menudo el uso del claros- curo en el cine negro para expresar la ambigüedad moral y la luz difuminada y luminosa para destacar la belleza asociada a la feminidad canónica y, muchas veces, a la bondad. La luz y las sombras se alternan, con efectos expresivos. Quizá una de las películas donde esto es más patente sea La Dama de Shangai, con los frecuentes primerísimos planos bajo la luminosa luz del sol, que nos muestran a los personajes deformados, casi monstruosos. Es de destacar también la improbable iluminación en la primera secuencia, donde todo está oscuro, pues es de noche, excepto el interior del carruaje en el que viaja Elsa Bannister, que parece tener luz propia para resaltar su cautivadora belleza. Entre sombras se nos presenta también por primera vez Eva Harrington (Anne Baxter) que espera, en la penumbra del callejón, a que le llegue su oportunidad de arrebatar a su idolatrada rival (Bette Davis) su papel dramático, su fama y, si es posible, también a su novio. La mundana transgresión de Joanne Woodward en Las tres caras de Eva se refleja en la extraordinaria interpretación de esta actriz, que recibió un Oscar por este filme. Y por último, Barbara Stanwyck en Perdición, se contonea en el entorno sofocante de su salón, en cuyas paredes las sombras de las persianas venecianas crean el efecto de una inmensa telaraña. La luz aterciopelada sobre su piel y el brillo que palpita en sus ojos, remite más a un modelo femenino cándido y positivo, por lo que está codificada como más maligna si cabe, a pesar de que, en términos objetivos, su acción real sobre el protagonista masculino es de mera sugestión. Otros rasgos visuales de la construcción de las “perversas” son los fetiches con los que se acompañan: objetos que simbolizan su sexualidad y su poder, como los cigarrillos, el guante de Gilda o la pulsera tobillera de Barbara Stanwyck. La puesta en escena de la célebrepresentacióndeGilda,despuésdetranscurridosveinteminutos de película, es un extraordinario ejercicio de dilación cinematográfica: