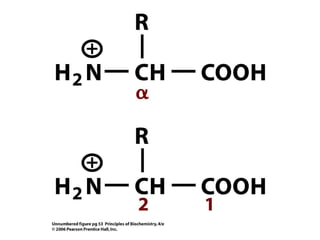

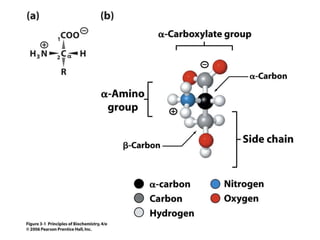

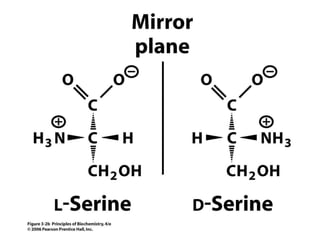

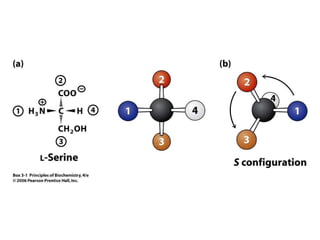

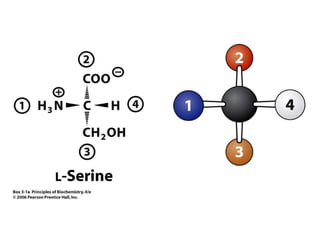

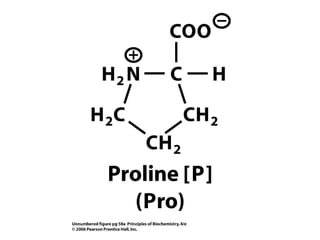

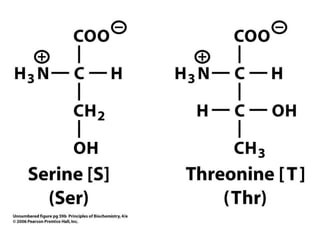

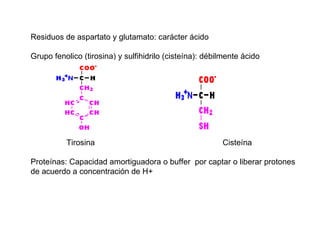

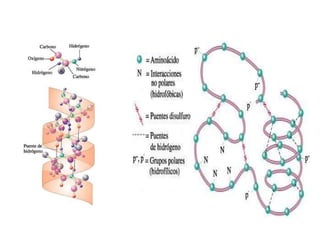

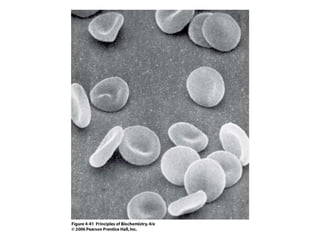

Este documento resume las propiedades y estructuras fundamentales de las proteínas. Las proteínas son macromoléculas compuestas por aminoácidos que cumplen funciones esenciales en los procesos biológicos. Su estructura primaria es la secuencia lineal de aminoácidos, mientras que las estructuras secundaria, terciaria y cuaternaria determinan su forma tridimensional mediante uniones como puentes de hidrógeno. Cambios en la secuencia o estructura pueden afectar la función de proteínas como la hem