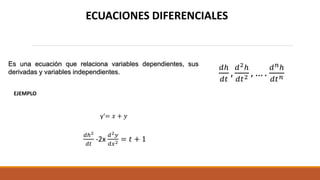

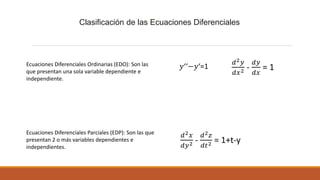

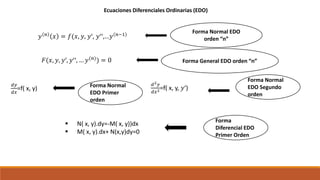

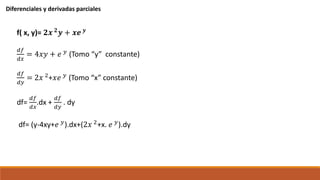

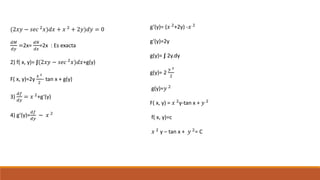

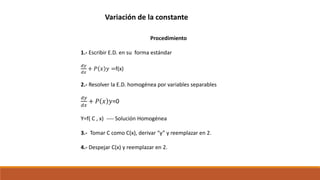

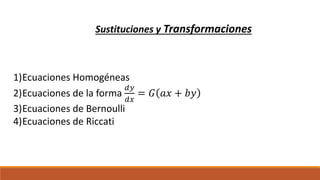

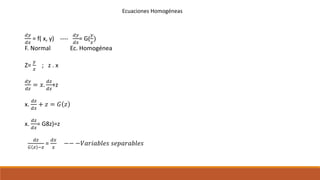

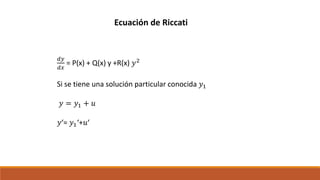

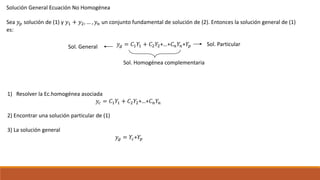

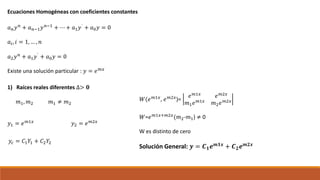

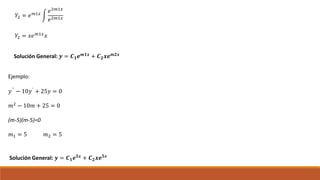

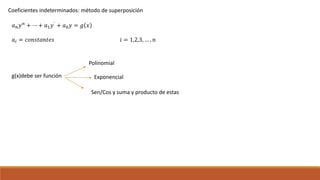

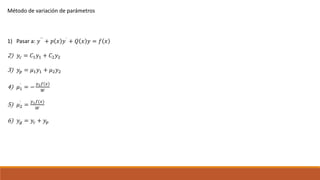

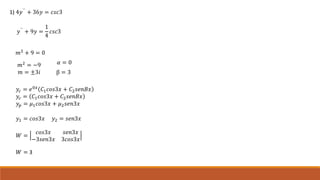

Este documento trata sobre ecuaciones diferenciales. Define ecuaciones diferenciales ordinarias y parciales, y explica conceptos como orden, linealidad, clasificación, soluciones, valores iniciales, variables separables, exactitud y variación de constantes.